Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

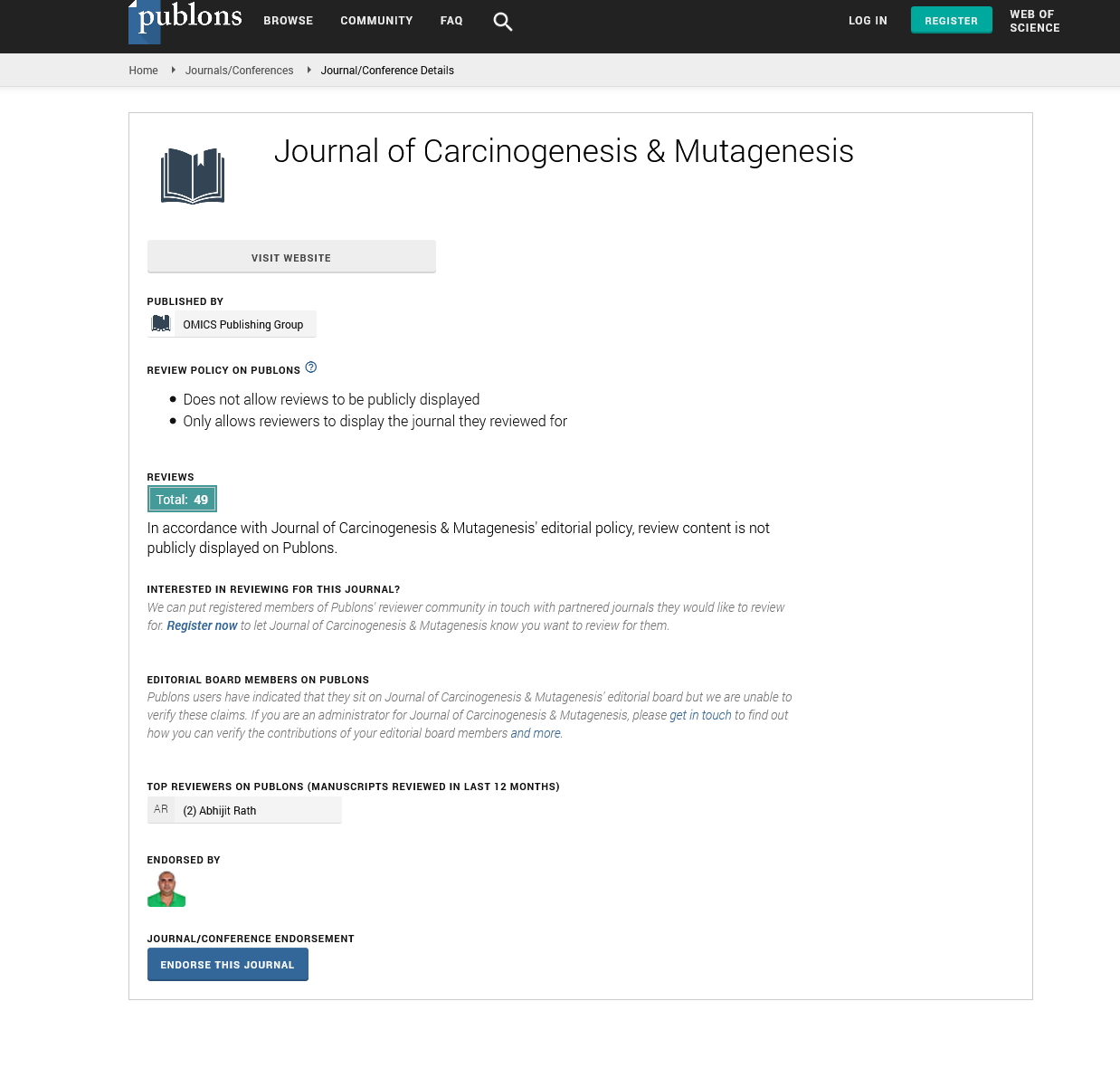

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

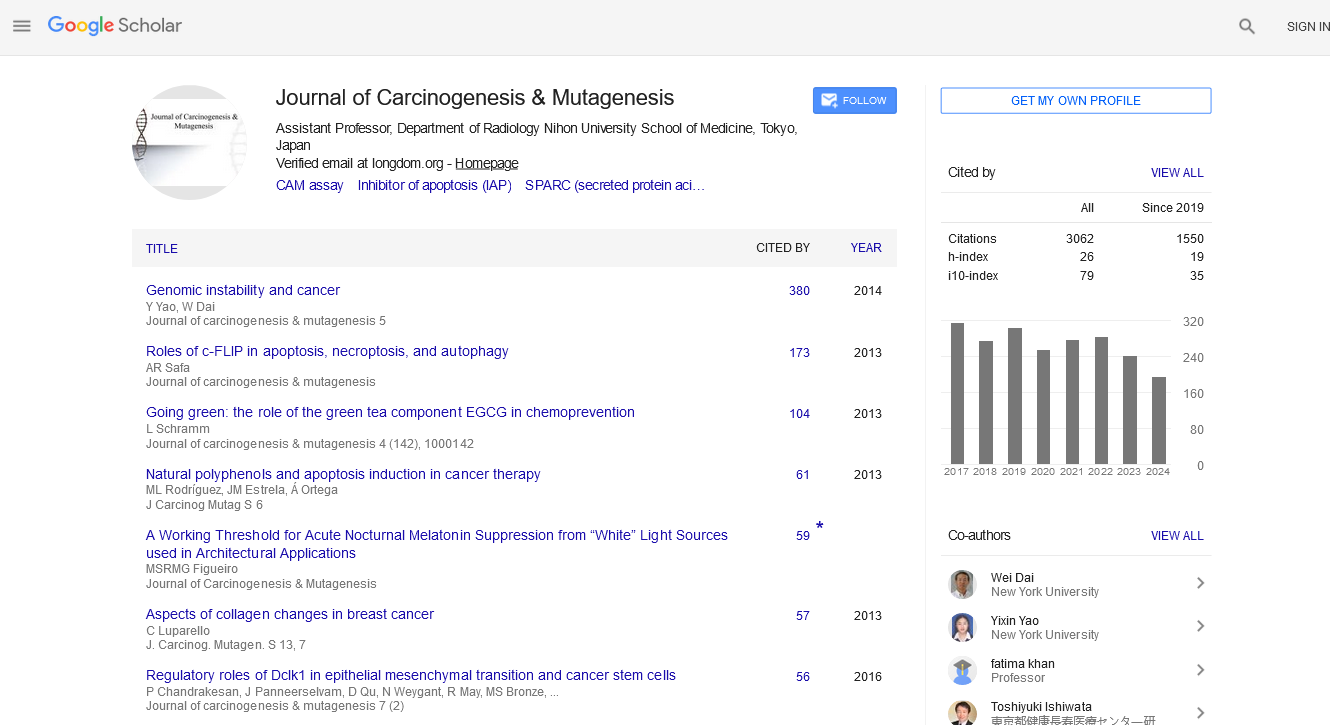

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Hospice: Where will the future of the Hospice lead us?

Annual Meeting on Asia Pacific Oncologists, Hospice and Palliative Care

May 13-14, 2019 Singapore

M Bercovitch

Tel Aviv University, Israel

Scientific Tracks Abstracts: J Carcinog Mutagen

Abstract:

Since ancient times, the obligation of the physician was to relieve suffering. Despite this fact, little attention was given to the problem of suffering and dying in medical education, research or practice. In the 21st century life expectancy is increasing, more people live with serious effects of chronic illnesses and they must deal with many complex issues: relief of symptoms, effect of the illness on roles and relationships, restoring or maintaining quality of life. Each of these issues creates expectations, needs, hopes and fears, which must be addressed in order for the ill person to adapt and continue living and presents a set of public health challenges requiring the attention of policy makers. Traditionally end of life care in the form of palliative care has been offered mostly to cancer patients. For some years this kind of care has been offered for a wider range of serious illnesses and was integrated more broadly across care services. Hospice was created as a coordinated program providing palliative care to terminally ill patients and supportive services to patients, families, 24 hours a day seven days a week. Services are comprehensive, case managed based on physical, social, spiritual and emotional needs during the dying process by medically directed interdisciplinary team consisting of patients, families, health care professionals and volunteers (WHO). Hospice treatment is the most personalized way to care, by recognizing a patient not only like a body part, but as a unique being, with soul and psyche. Each patient means a new book to be read and understood by the team. Hospice program is limited for those patients diagnosed with terminal illness with a limited life spam and it is not a must in health care system. Hospice is a choice and any individual has the right, in conformity with the law, to decide how to be treated when facing a terminal illness. Those patients refusing to accept the imminence of death and want to continue to fight they are not eligible for hospice. Those prefer to concentrate on living as comfortably as they can until their last day prefer the hospice care.

Biography :

Michaela Bercovitch is the director of the Oncological Hospice in Sheba hospital, Tel Hashomer, Israel and a lecturer at Tel Aviv University Sackler School of Medicine. Dr. Bercovitch was born in Romania, Bucharest, where she graduated from medical school as MD in Pediatrics. In 1987 she emigrated to Israel and after two years training in Internal Medicine and Geriatrics she continued her medical practice in the Oncological Hospice. In 1998 she initiated a 2 year comprehensive postgraduate course of Palliative Medicine for doctors. She is involved in the education of medical students, nurses and doctors across Israel. Her research fields include pain control, impact of high dose opioids on patients’ survival, development of clinical auditing tools and a hospice oriented clinical database. She is the author of the chapter discussing treatment of pain with TENS (Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine), and other chapters addressing euthanasia, non-pharmacological treatments for chronic pain, the role of the physician near death, and the effect of patient-setting on the work of the team. Dr. Bercovitch was a member of the Directory of European Association for Palliative Care (2007-2016); Served as the Chairperson of Israeli Palliative Medicine Society (2002- 2016) focusing on the recognition of Palliative Medicine as a sub-specialty and its inclusion as a government-funded treatment. Along the years she has actively participated in the conception and promulgation of the first Israeli law regarding the dying patient.

E-mail: almi@sheba.health.gov.il