Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

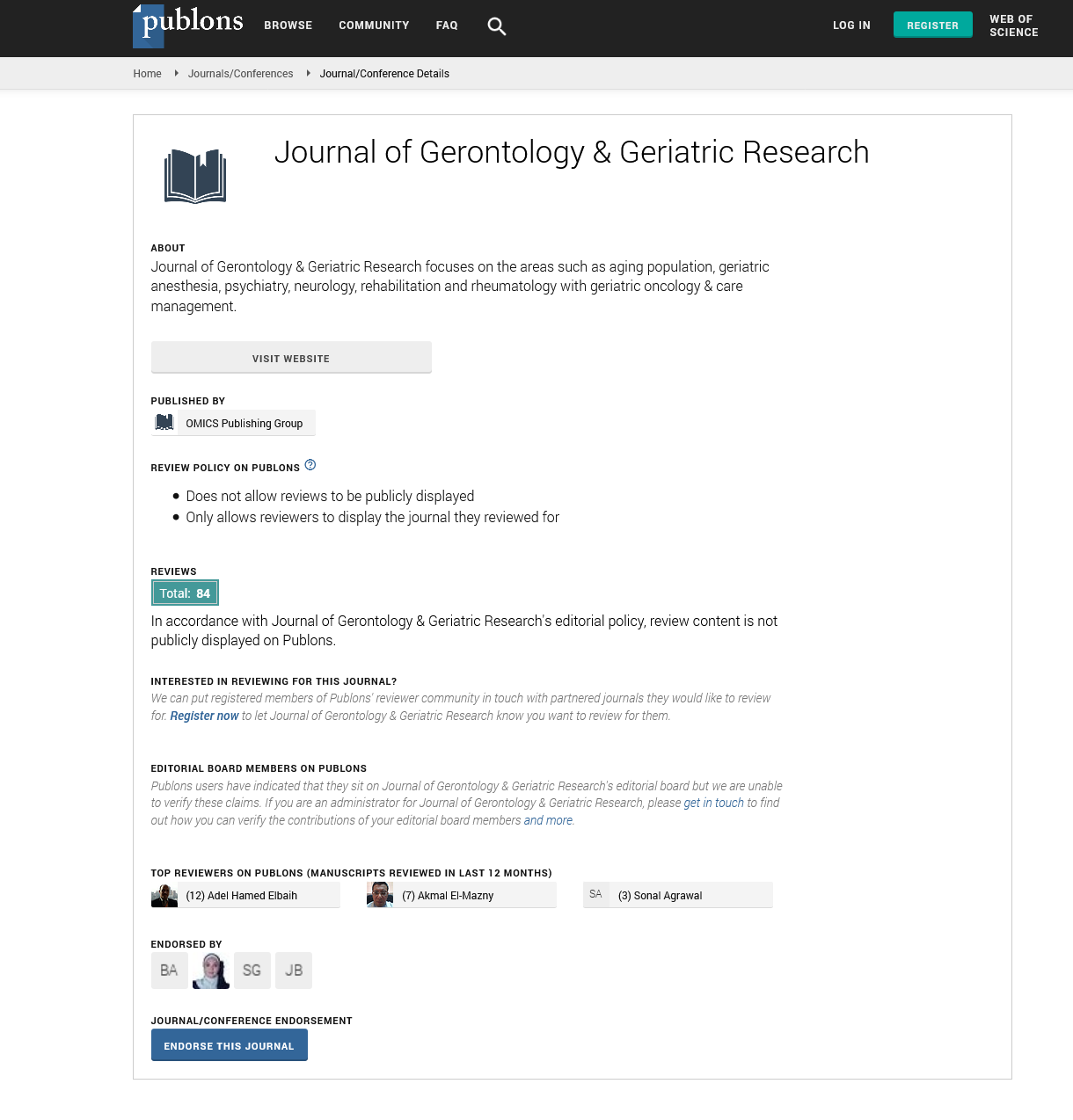

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Perspective - (2021) Volume 10, Issue 9

Insomnia Treatment in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment

Ramel Jonsson*Received: 09-Sep-2021 Published: 30-Sep-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2167-7182.20.10.573

Perspective

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI, called "pre-dementia") is a critical juncture between normal cognition and dementias like Alzheimer's disease (AD). MCI affects up to 20% of older persons, with an annual conversion rate of 8-15% to dementia. Sleep disruptions and deprivation, a recognised cardinal pathophysiological aspect of AD, can raise levels of beta-amyloid and phosphorylated tau, a known cardinal pathophysiological feature of AD, and contribute to impaired global cognition. People with Alzheimer's disease have a higher inflammatory response, which increases beta-amyloid formation. Sleep deprivation has been linked to the advancement of Alzheimer's disease and may inhibit interstitial fluid outflow through the cerebrospinal fluid into the interstitial space, which helps to eliminate beta-amyloid and phosphorylated tau from the brain. This increased beta-amyloid generation is especially concerning because insomnia symptoms have been linked to a reduction in the brain's ability to eliminate beta-amyloid plaques. Although the specific mechanisms are unknown and may be bidirectional or linked, sleep may play a role in the course of Alzheimer's disease, with better sleep promoting cognitive performance.

Because sleeplessness is widespread in people with MCI, evaluating and treating insomnia offers a way to intervene in the early stages of cognitive impairment in illnesses that have no known cure. According to current guidelines, non-pharmacological Cognitive- Behavioural Therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) should be used first in the treatment of insomnia, with pharmaceutical intervention being used only if CBT-I is ineffective or unavailable. Our primary goal was to assess existing non-pharmacologic therapy in older persons with MCI, including CBT-I, based on current guidelines and the risks of polypharmacy in older adults with cognitive problems. We discovered that many research just do not exist in sufficient numbers to warrant a review. As a result, we give a summary of selected research and guidelines for the most often used pharmacological therapy in this patient population. Clinical trials of CBT-I in this at-risk senior group, we conclude, are urgently needed.

By searching PubMed, PyscInfo, and Web of Science for nonpharmacological sleep therapies in older persons with MCI, a review was conducted. Sleep, sleep-wake, circadian, insomnia, sleep initiation and maintenance disorders, sleep disruption, mild cognitive impairment, cognitive dysfunction, and neuropsychiatric symptoms were among the terms utilised in the search. MCI diagnosis, intervention studies, human volunteers, and sleep disturbance with pre- and post-measurement were all included in the study. Participants who were diagnosed with MCI had to go through a neuropsychological evaluation that included multiple tests.

Studies that used simply the Mini-Mental Status Examination as the neuropsychological assessment, for example, were not included in this review. Subjective complaints of cognitive impairment for MCI diagnosis or a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease, traumatic brain injury, rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder, spindle density, or multiple sclerosis were all considered exclusion criteria. The outcome was cognitive status, as determined by at least one or more neuropsychological evaluations (s). The majority of the publications that did not match the inclusion or exclusion criteria looked at a broad range of sleep disorders rather than just insomnia.

The review's most surprising conclusion is that only one therapy for improving insomnia symptoms in MCI patients was eligible for discussion. One cause for this is the continued use of pharmaceuticals. We underline our reservations about the use of sedative-hypnotic drugs in the elderly. The probability of unfavourable side effects, medication interactions, and polypharmacy interactions increases as people age. When utilising classic benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonist sleep aids like zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zaleplon, age-related concerns is especially troubling. Traditional sleep aids have been linked to major side effects in older persons, including cognitive impairment and falls.

Citation: Jonsson R (2021) Insomnia Treatment in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 10: 573

Copyright: © 2021 Jonsson R. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.