Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Case Report - (2021) Volume 10, Issue 7

Homicide-Suicide in Older Couples

Renard L*, Malbranque S and Jousset NReceived: 06-Jul-2021 Published: 26-Jul-2021

Abstract

Spousal homicide-suicide refers to the discovery of two bodies in the same location and, in most cases, to cases where a wife is killed by her husband. It involves a particularly violent crime scene. Among the objectives of the forensic analysis, the estimation of the chronology of the events leading to the suicide and the determination of the causes of deaths, which appear as more or less self-evident at first glance, sometimes require an autopsy, if this is the direction that the investigators choose to follow. In this article, we describe the homicide-suicide of an elderly couple by mechanical asphyxia. A post-mortem examination was carried out on site and the intervention of a third party was formally ruled out. The description of this case allows us to highlight the different characteristics of homicidesuicide, notably among elderly couples, and to emphasize the particularity of the suicidal mechanism used in these cases and the underlying psycho-social context.

Keywords

Homicide-suicide; Older couple; Asphyxia; Elderly couples; Rheumatology; Cancer

Introduction

Homicide-suicide (HS) has been traditionally defined as homicide followed by the suicide of the perpetrator. Different types exist. In the family context, the most common forms are the so-called spousal HS with “altruistic” motives [1], also known as uroxicide (designating a wife’s murder by her spouse), often in the context of depression, chronic alcoholism, domestic violence and or jealousy, with suspicions of adultery, and or a desire of the woman to separate from her husband. It represents 20% of all homicides, i.e., approximately 170 deaths per year in France in 2019 [2]. Spousal HS with “mercy” motives often concerns an elderly couple (the perpetrator is 55 years old or older), with at least one of the spouses suffering from a serious medical or physical condition. The symptoms reported are often associated with chronic pain, rheumatology, or cancer, which become difficult to bear (and for which patients do not always receive sufficient care). The conditions may also be psychological, requiring even more specific medical care (hospitalization). The other member of the couple (“in good health”) is likely to become the primary caregiver. It is worth mentioning that, unlike “altruistic” spousal HS, the couples in the “mercy” case are not in conflict. The act of homicide is therefore conceived as some form of deliverance, lessening the other’s sufferings, a form of “homicide by compassion”, quickly followed by suicide, so that the couple leave “together” with the possibility of meeting again or obtaining rest in the afterlife. This act often takes the form of a “suicide pact”. Evidence suggests that the perpetrator is often a man experiencing depression [3].

According to epidemiological data collected by Vandevoorde et al., [1] the frequency of all HS’s in France is estimated at 0.2 to 1.55 per 100,000 inhabitants; in England, at 0.05 per 100,000, or 23 cases per year, and in the United States at 0.27 to 0.38 per 100,000, approximately 1,000 to 1,500 deaths per year.

Case Report

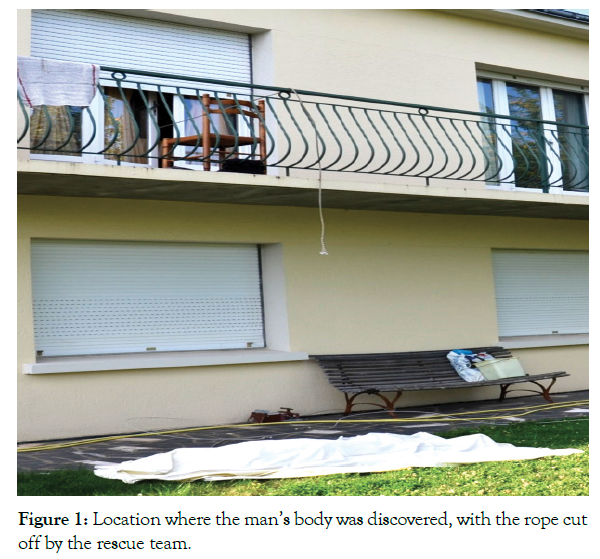

The bodies of an 84- and 86-year-old married couple were discovered in the kitchen and outside their home by a neighbor. This neighbor had alerted the rescue services in the late afternoon after seeing a body hanging on the balcony of a detached home, in the garden, with a chair placed next to the balcony railing.

The interior of the house was orderly, with no sign of theft or any apparent disorder. The house had been locked and the keys were still on the door on the inside (the rescue team had to pass through the kitchen window).

Description of the bodies

When the medical examiner arrived, the man’s body was lying in a supine position on the grass, a white rope around its neck, which the rescue team had cut off upon arrival. He had been suspended from the balcony rail overlooking the garden in a situation of partial hanging, i.e., with his feet still touching the ground. He was dressed normally, without any disorder, and was barefoot. Next to the body on the ground were two hearing aids (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Location where the man’s body was discovered, with the rope cut off by the rescue team.

The examination of the body revealed a tongue protrusion (which is a typical finding in a hanging death), a purplish contusion on the extreme end of the nose, non-specific dermabrasions of the posterior cranial base, and of the upper and lower limbs. The body on the ground had the characteristics of livor mortis. This cadaveric lividity was not yet fixed. The post-mortem interval was estimated at just a few hours. The position of the rope around the neck was perfectly compatible with an intentional hanging, i.e., except for the area around the knot, there was a groove across the neck, high up, facing rearwards, surrounding the neck almost completely. The cutaneous groove perfectly reproduced the imprints of the rope and the skin appeared “leathery”, dissected even.

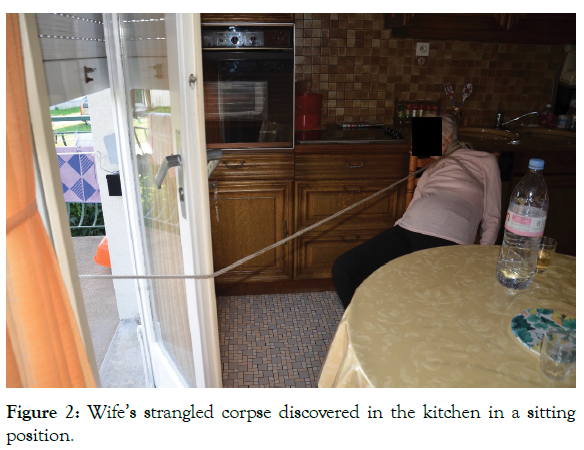

The rope was attached by one single turn around the balustrade overhanging the corpse. On the balcony, there was a chair with the backrest against the balustrade rail. On the chair was a watch, and on the ground a pair of slippers and a pullover. This same rope made its way through a half-open window and entered the house through the kitchen (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Wife’s strangled corpse discovered in the kitchen in a sitting position.

The lifeless body of the wife, seated on another identical chair in a slightly slumped position, was also discovered. The rope had been wound three times around her neck and was held in position by two loops on each side of the back of the chair. The body was dressed normally, in a pullover, pants and shoes. Close to the body was a pair of crutches lying on the kitchen furniture. An examination of the body revealed no injuries. The body displayed livor mortis that conformed to the position in which the body had been found. Like her husband, the post-mortem interval was estimated at a few hours. After the removal of the rope, there appeared an incomplete ligature mark which was non-parched, supraglottic, and stretched upwards toward the back.

Description of the location

Further research inside the home led to the discovery, on the dining-room table, of many elements essential to the investigation and explaining the HS act. There were four handwritten letters, two written by each of the spouses to their child; there was also a letter for the brother of the deceased and a sixth one for a family acquaintance. Essentially, the writings evoked relief from the end of chronic pain, the challenges of everyday life, and the absence of any hope for a cure, as well as a plea for divine liberation and the happiness of leaving this world. A funeral contract was also present. Next to all these elements was a glass containing partially dissolved, unidentifiable pill residues.

Legal proceedings

After the examination of the body was completed, and after discussions with the prosecutor, the latter concluded that the manner of death was homicide-suicide and terminated the prosecution (abandonment of legal proceedings because of the death of the perpetrator). The magistrate ordered neither an autopsy nor a toxicological analysis of the bodies or of the glass found near the letters. The investigation was concluded with the terms “absence of an infringement”.

Case Study

This case study highlights the existence of a “suicide pact” between this elderly couple. Sickness and suffering were a daily companion, they saw each other deteriorate, and they were no longer able to perform everyday tasks that they had been able to do until recently. The “only possible way out” for these loving spouses was to leave together and to meet again, without the pain, after death. One would take the life of the other, then shortly after their own. This situation is similar to the Greek legend of Philemon and Baucis, where Zeus and Hermes decide to descend on Earth disguised as mortals and seek accommodation for the night. However, no one agrees to host them. They come across Philemon and his wife Baucis, a couple of old Phrygians who, despite their humble house thatched with reeds, welcome them with open arms. To thank them, the gods turn their simple hut into a temple and grant them a wish. Their dearest wish is to die together. Thus, when the time comes, the soul mates are changed into an intertwining pair of trees: an oak tree for Philemon and a linden tree for Baucis.

In forensic medicine, this eponymous syndrome corresponds to the discovery, in the same location, of two bodies whose post-mortem interval is almost identical, often at the home of an elderly couple, when one of the partners dies of natural causes. When the other spouse discovers the lifeless body of their other half, they die from acute heart failure because of intense stress, often because they already have an underlying cardiovascular condition [4-6].

While the cause of death of the couple described in this article was intentional, rather than natural causes, the bodies were found in the same location, with a similar estimate of the post-mortem interval, and with letters from each partner expressing their distress in the face of their weakness and their desire to be relieved of their suffering. The main assumption of this crime scene is the homicide of the wife by her spouse by mechanical asphyxia through strangulation with a rope, followed by the husband’s suicide by hanging, with the bodies linked, quite symbolically, to the same rope. Logan et al. [7] found that, in England and Wales, 40% of HS perpetrators had requested medical treatment in the month preceding the act, thus leaving room for the prevention of the risk that they would execute the scenario. In our case, the investigation revealed that the couple’s son had contacted them the day before the incident and they had clearly expressed their malaise and their intentions. Law-enforcement officers had therefore intervened to remove firearms from their home. However, this had proved insufficient to protect the couple from their desire to “leave together”, using a simple and easily accessible manner.

Discussion

In acts of suicide, the most widely used method in France, regardless of age, is hanging. This method has the “advantage” of being quick and easily executable, with little or no pain, and no significant deterioration of the body.

Hanging is a relatively common self-inflicted act and forensic autopsies are not systematically performed in such a context. Physicians must carefully examine the body of an individual who has died by hanging to avoid omitting stigmata that may suggest the intervention of a third party (integumentary lesions known as “gripping” and/or struggle, atypical hanging groove…) and they should propose a forensic autopsy if there is any doubt [8,9].

Criminal hangings involve either an aggressor who is physically stronger than their victim, a victim in an altered state of consciousness, or several perpetrators to control the victim. Homicidal hanging is thus quite a rare event [8,9]. In our case study, the hypothesis of an established suicidal pact suggests that the woman showed no opposition to the placing of the rope around her neck (absence of any sign of associated violence), unless a chemical restraint had been used through the administration of the drugs present in the couple’s home. Other common methods of suicide in France, by order of frequency, are firearm suicides and drug overdoses. In the United States, firearm suicides are more frequent because of the easy access to weapons. The most frequent risk factors for suicide in the elderly include melancholic depression with intense emotional strain, pathologies leading to impaired cognitive functions such as dementia, chronic alcohol consumption, social isolation and loneliness [10]. The victim’s only “way out” of this suffering thus becomes self-inflicted death. The typical profile most often corresponds to a man living alone or recently widowed, suffering from crippling chronic pathologies and living in either an urban or rural environment, contrary to the common belief that people living in the countryside are lonelier [11-16].

While aging is a process that involves successive losses (loss of loved ones, loss of autonomy, loss of one’s home and one’s reference points following admission into a care establishment) and thus favors the emergence of symptoms of depression, not all elderly people are depressed, and sadness is not a normal response to aging. This therefore means that depressive symptoms should never be trivialized, and that they may differ from those exhibited by young adults. Indeed, these symptoms are often concealed, less pronounced, more insidious, and therefore harder for healthcare professionals to identify. They may take the form of generalized anxiety, somatic disorders such as palpitations, feelings of having a “lump in the throat” or tightness, nervousness, irritability, psychomotor agitation, or obsessive ideas, or they may also include cognitive symptoms such as a loss of memory [12]. General practitioners must therefore be capable of recognizing these signs to be able to treat them, and they must also be willing to undertake prevention work.

Depression is never the only trigger that makes people carry out the act. Major “loss life” events, such as the death of a spouse, estrangement from the family, loneliness, institutionalization (long-stay hospitalization or in a home for the elderly), poverty, job insecurity, serious physical illnesses, or even pain, handicap, dependence and leaving one’s home [13], all act as a detonator (a real “trigger”) that may lead to the carrying out of a suicidal act. The study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) / EURO Multicenter Study of Suicidal Behavior in 13 European countries showed that the death rate by suicide among people over 65 stood at 26.3 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a suicide attempt rate of 61.4 per 100,000 inhabitants. In France, the European country with the most suicides, there have been approximately 10,000 cases per year over the past 10 years, with 30% of the victims aged over 65 (i.e., 3,500 deaths per year). Most of these victims are men and most committed suicide by hanging or by using a firearm, meaning an incidence rate of 50.5 per 100,000 inhabitants per year [13-18].

There is evidence that, while older people make fewer suicide attempts, these attempts are generally more successful than in younger populations. Concerning the letters left by victims, the characteristics differ according to the age of the author [14]; older people tend to write shorter texts, with precise instructions on what to do after their death, and generally have fewer messages expressing their feelings or special messages for the family they leave behind.

Given that we focus specifically on the elderly, it seems important to clarify how we define this term. According to WHO, a person becomes old from the age of 60 (it is also at this age that one becomes eligible to access nursing homes in France (EHPAD)). However, generally speaking, admission to geriatric care is only possible from the age of 75. Eurostat, the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (Insee), the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES), and the PubMed database all indicate that one may be referred to as an elderly person from age 65. The retirement age is also a strong social marker: for instance, it is set at 62 in France, 65 in Germany and 66 in the United Kingdom. This information shows that it is difficult to have a consistent definition between different countries, and even within the same country, of when someone can be referred to as old. According to geriatricians, there are several categories of elderly people: the robust elderly (about 70% of the population considered) who experience successful aging; the frail elderly (20%) who are at risk of moving into the last category; and the dependent elderly (10%), dependent because of pathological aging. The concept of civil age thus disappears in favor of an individual’s general state of health [19-21].

In this situation, where there is a proven risk of suicide, the need for urgent medical care (hospitalization, institutionalization) to remove couples from their anxiety-provoking environment and protect them from their mutual suicidal thoughts seems imperative.

Treating melancholia which, as is well known, plays a role in this end-of-life scenario, also appears essential.

A Belgian study reported the case of a 78- and 83-year-old couple where the man had terminal cancer and his wife rheumatoid arthritis. It seemed impossible for the woman to continue living without her husband. Although active euthanasia is a legal act in Belgium, the wife was not eligible for this (she was not suffering from a pathology considered to be “serious and incurable” and was not in an “end-of-life” situation). Yet, against all odds, the doctors complied with the couple’s request on the grounds of “unbearable suffering”, i.e., suffering that was of exclusively psychological origin [15].

Without taking any sides in the debate concerning assisted suicide, the authors questioned whether, in light of the relevant legal provisions in the countries that allow this, there were fewer HSs among the elderly compared with those countries where this act was prohibited (something we are unable to analyze with our current references). If so, they questioned whether this figure would be lower not because of the euthanasia itself, but rather because of a paradoxical effect associated with the fact that a suffering couple receives medical and psychological care. This support may help to improve the end-of-life conditions and address the anxieties experienced. Thus “reassured”, such a couple could therefore enjoy this phase of old age peacefully by abandoning their ideas of murdering one another [22,23].

Conclusion

In this article, we describe the homicide-suicide of an elderly couple by mechanical asphyxia. A post-mortem examination was carried out on site and the intervention of a third party was formally ruled out. The description of this case allows us to highlight the different characteristics of homicide-suicide, notably among elderly couples, and to emphasize the particularity of the suicidal mechanism used in these cases and the underlying psycho-social context.

REFERENCES

- Vandevoorde J, Estano N, Painset G. Homicide-suicide: Revue clinique et hypothèses psychologiques. L’Encéphale. 2017;43(4):382‑393.

- https://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Archives/Archives-des-communiques-de-presse/2020-communiques/Etude-nationale-relative-aux-morts-violentes-au-sein-du-couple-en-2019

- Saint MP, Bouyssy M, O’Byrne P. Homicide-suicide in Tours, France (2000-2005) description of 10 cases and a review of the literature. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15(2):104‑109.

- Ciesiolka S, Risse M, Busch B, Verhoff MA. Philemon and Baucis Death? Two cases of double deaths of married couples. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008;176:e7‑10.

- Lardi C, Schmit G, Burkhardt S, Mangin P, Palmiere C. Philemon and Baucis Deaths: Case Reports and Postmortem Biochemistry Contribution. J Forensic Sci. 2014;59(4):1133‑1138.

- Delannoy Y, Tournel G, Dedouit F, Cornez R, Telmon N, Hedouin V, et al. Philemon and Baucis syndrome: Three additional cases of double deaths of married couples. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;226:e32‑6.

- Logan JE, Ertl A, Bossarte R. Correlates of intimate partner homicide among male suicide decedents with known intimate partner problems. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(6):1693‑1706.

- Monticelli FC, Brandtner H, Kunz SN, Keller T, Neuhuber F. Homicide by hanging: A case report and its forensic-medical aspects. J Forensic Leg Med. 2015;33:71‑75.

- Sharma L, Khanagwal VP, Paliwal PK. Homicidal hanging. Int J Legal Med. 2011;13(5):259‑261.

- Frénisy MC, Plassard C. Le suicide des personnes âgées. Soins. 2017;62(814):39‑41.

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack SPD, Haileyesus T, Kresnow SM. Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death. USA, 2001-2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2017;66(18):1-16.

- Crestani C, Masotti V, Corradi N, Schirripa ML, Cecchi R. Suicide in the elderly: A 37-years retrospective study. Acta Bio Medica. 2019;90(1):68‑76.

- De Souza Minayo M, Gonçalves CF. Suicide in elderly people: A literature review. Rev Saúde Pública. 2010;44(4).

- Rahimi R, Ali N, Noor S, Mahmood MS, Zainun KA. Suicide in the elderly in Malaysia. Malays J Pathol.2015;37(3):259-263.

- https://www.ieb-eib.org/fr/actualite/fin-de-vie/euthanasie-et-suicide-assiste/euthanasie-simultanee-d-un-couple-131.html

- Gunnell D, Bennewith O, Hawton K, Simkin S, Kapur N. The epidemiology and prevention of suicide by hanging: A systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(2):433‑442.

- Gunn JC. Extended suicide, or homicide followed by suicide. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2019;29(4):239‑246.

- Knoll JL, Hatters FS. The Homicide-suicide phenomenon: Findings of psychological autopsies. J Forensic Sci.2015;60(5):1253‑1257.

- Regoeczi WC, Gilson T. Homicide–suicide in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, 1991–2016. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(5):1539‑1544.

- Bell CC, McBride DF. Commentary: Homicide-suicide in older adults- Cultural and contextual perspectives. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(3):321-327.

- Cohen D, Llorente M, Eisdorfer C. Homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(3):390‑396.

- Zupanc T, Agius M, Paska AV, Pregelj P. Blood alcohol concentration of suicide victims by partial hanging. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013;20(8):976‑379.

- Gourion D. Événements de vie et sévérité de la dépression aux différents âges de la vie. L’Encéphale. 2009;35:S250‑256.

Citation: Renard L, Malbranque S, Jousset N (2021) Homicide-Suicide in Older Couples. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 10: 561.

Copyright: © 2021 Renard L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.