Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

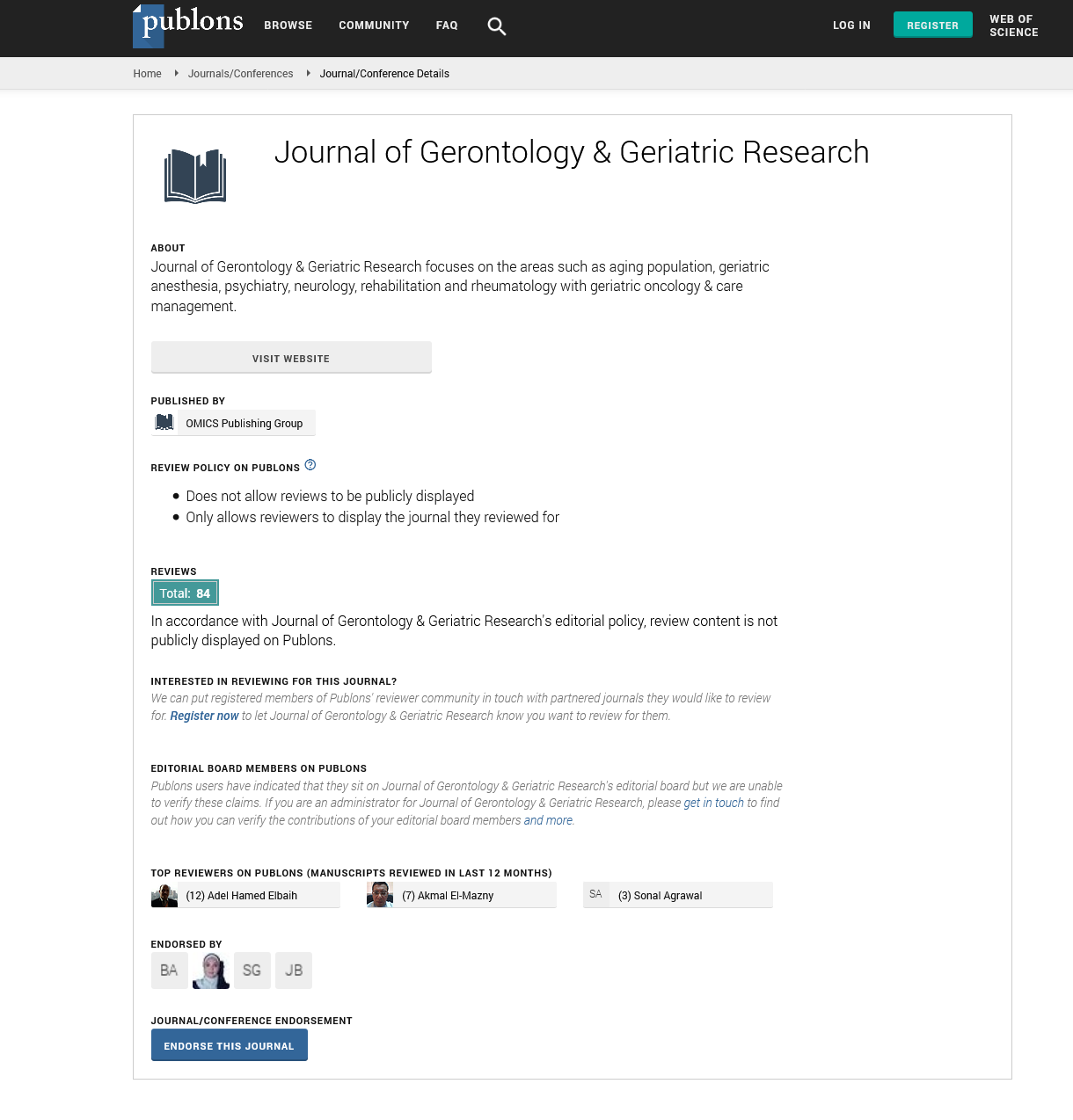

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Review Article - (2022) Volume 11, Issue 7

Healthcare aide-focused interventions to improve pain management

Jennifer Knopp*Received: 02-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JGGR-22-18157; Editor assigned: 04-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. P-18157; Reviewed: 14-Jul-2022, QC No. Q-18157; Revised: 20-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. R-18157; Published: 25-Jul-2022, DOI: 10.35248/2167-7182.2022.11.624

Abstract

Patients frequently seek medical attention due to chronic pain, which places a heavy strain on those who are impacted. People with chronic pain may find assistance from in-person psychological therapy, although these programmes are not always available. While eHealth interventions may increase accessibility, there is currently a dearth of data supporting their usage and the development of digital self-management tools for chronic pain, which raises questions about the involvement of healthcare professionals in their creation. The current study's objective was to learn more about the experiences of healthcare professionals treating patients with chronic pain, their attitudes toward and use of digital pain management solutions, and their recommendations for the content and design of a potential digital pain self-management intervention [1].

Keywords

Pain Management; Digital Self-management; Healthcare

Introduction

Due to considerable obstacles in accessing sufficient care, patients with acute and chronic pain in the United States are in a crisis, which has significant negative effects on their physical, psychological, and social well-being. 50 million persons in the United States suffer from chronic daily pain, with 19.6 million of those adults enduring high-impact chronic pain that interferes with daily activities or employment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Our country's annual cost of suffering is estimated to be between $560 and $635 billion. The opioid problem that has plagued our country for the past ten years has led to an unprecedented number of overdose deaths involving heroin, prescription opioids, and synthetic opioids [2].

Description

Over 100 million Americans suffer from chronic pain, and the majority of these people receive assistance from a medical aid provider, who accounts for one-third of all visits to medical help. However, because to limit pain care coaching and a general lack of confidence in their capacity to successfully manage pain, medical aid suppliers continue to provide subpar pain treatment. Wherever pain is very prevalent, models to improve pain outcomes are created but not formally implemented. The SCM-PM suggests a 3-step tailored method for treating pain. The practitioner analyses the patient's pain concerns in Step 1, discusses them, and then builds a treatment plan that focuses on self-management and first care-based interventions. Step two entails additional resources and collaborative therapy [3].

Chronic pain can be minor or severe, intermittent or constant, mildly bothersome or completely incapacitating. It eventually gets more challenging for the patient to distinguish the precise location of the pain and properly define the pain's intensity. Some people may experience chronic pain without any prior injuries or signs of physical harm. It might restrict motion, which could weaken the person's strength, stamina, and flexibility. This inability to perform necessary and enjoyable activities might result in incapacity and hopelessness. Because the patient might not appear to be in pain, family members, friends, co-workers0., employers, and healthcare professionals may doubt the validity of the patient's pain reports. The patient may potentially be utilising their discomfort to either avoid or attract attention [4].

Pain management strategies

According to studies, a person's emotional health might affect how they perceive pain. Your quality of life can be enhanced by comprehending the underlying problem and discovering practical pain management techniques. Medication is one of the most important pain management techniques.

• Bodily exercises (such as heat or cold packs, massage, hydrotherapy and exercise)

• Psychiatric interventions (such as cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation techniques and meditation)

• Mental and physical exercises (such as acupuncture) communities of support.

"There might be a strong desire to enhance pain management in healthcare. This effort was heavily focused on protocol-driven care, supplier education, and unquestionably minor but essential improvements in data, self-efficacy, and adherence to guidelines! If these findings are confirmed, patient outcomes may be improved. Positive shifts in referral patterns and opioid prescribing suggest that structured improvement activities supported by data and efficient abstract models will not only increase the amount of information acquired, but also the ways in which it is applied in ways that directly affect patient care. These adjustments appear to have the desired effects of reducing pain, enhancing patient safety, and adding more confident, competent, and content health care groups.

Painkillers function in a variety of ways. Aspirin and other NSAIDs are anti-inflammatory and fever-lowering painkillers. They accomplish this by blocking substances known as prostaglandins. Prostaglandins make nerve endings sensitive, which increases inflammation and swelling, and can cause pain. Prostaglandins also aid in protecting the stomach from stomach acid, which is why some people may experience irritability and bleeding when taking these medications. Opioid medications function differently. These medications can be addictive because they alter the way that the brain processes pain signals [5].

The information was broken down into three main themes: Patients with chronic pain and their current use of healthcare services; Health care providers' own motivation and impression of patient requirements for use of digital self-management interventions; and Suggestions for content and design elements in a digital self-management intervention for those who are dealing with chronic pain. Patients with chronic pain were said to suffer a variety of difficulties. Few of the healthcare professionals have used or suggested eHealth solutions to their patients, despite curiosity and favourable sentiments. The necessity of easy access and positive, individualised material to support current therapy was stressed by clinicians along with a variety of prospective content and functionality factors, including aspects of motivation and engagement.

Conclusion

Thematic analysis was used to examine the transcripts. Three of the writers (CV, ILS, and HE) familiarised themselves with the material in the first stage of the study by listening to the recordings, reading the transcripts, and taking notes separately. The transcripts were then deductively coded by CV and ILS using the NVivo version 11 programme (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) into three pre-defined overarching themes based on the interview guide: A future digital chronic pain self-management intervention will need to meet the following criteria:

o Provider-identified patient characteristics

o Treatment and follow-up provided to patients with chronic pain

o Interviewee's experience using technology

o Identified needs and requirements. New themes were allocated to data that couldn't fit into the predefined ones.

REFERENCES

- Todd KH. “Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study.” J Pain. 2007;8:460-466.

- Cordell WH. “The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care.” Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:165-169.

- Tanabe P and Buschmann M. “Emergency nurses' knowledge of pain management principles.” J Emerg Nur. 2000;26:299-305.

- Latina R. “Attitude and knowledge of pain management among Italian nurses in hospital settings.” Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16:959-967.

- McCaffery M. “Nurses' personal opinions about patients' pain and their effect on recorded assessments and titration of opioid doses.” Pain Manag Nurs. 2000;1:79-87.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Citation: Knopp J (2022) Healthcare Aide-Focused Interventions to Improve Pain Management. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 11: 624.

Copyright: © 2022 Knopp J. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.