Indexed In

- CiteFactor

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Scholarsteer

- Publons

- Euro Pub

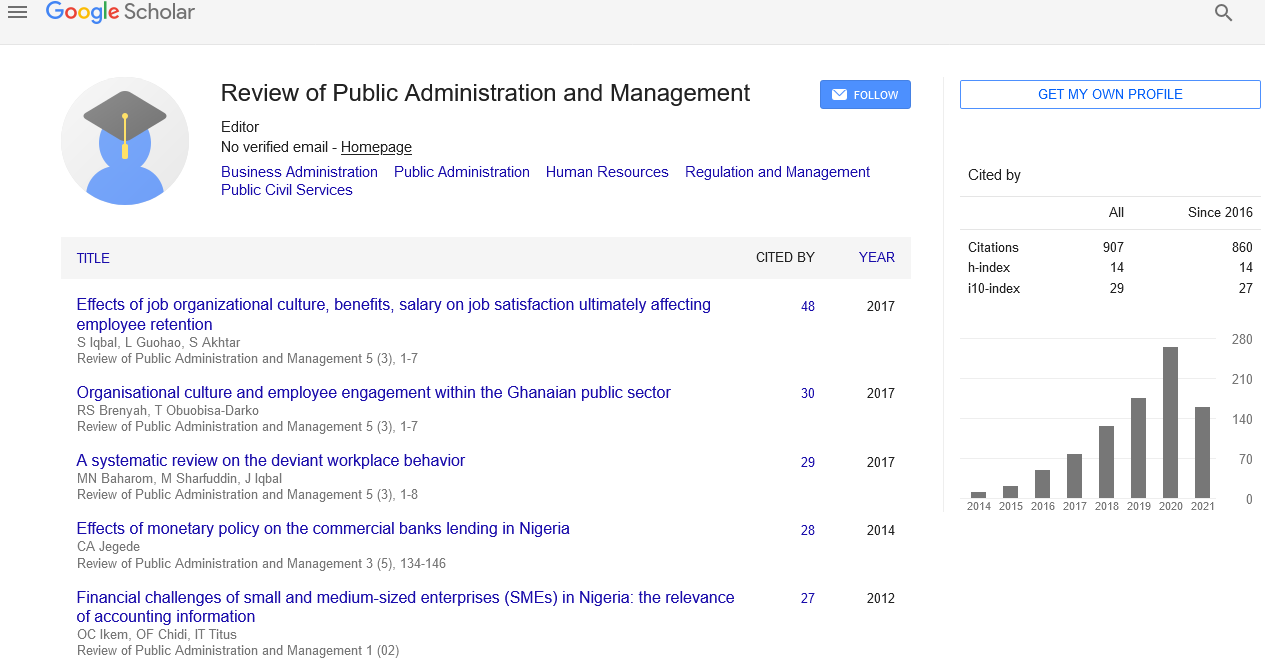

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Perspective - (2025) Volume 13, Issue 2

Ethics and Accountability in Public Service Delivery

Emily Brown*Received: 02-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. RPAM-25-29753; Editor assigned: 04-Jun-2025, Pre QC No. RPAM-25-29753; Reviewed: 17-Jun-2025, QC No. RPAM-25-29753; Revised: 21-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. RPAM-25-29753; Published: 28-Jun-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2315-7844.25.13.489

Description

Ethics and accountability form the moral and functional foundations of public administration. Without them, institutions risk losing legitimacy, efficiency and public trust. The essence of public service lies in serving the community impartially, fairly and responsibly. While policies provide the framework for action, ethics and accountability ensure that these actions remain aligned with the values of justice, equity and responsibility. Across different countries and administrative traditions, the significance of these two principles has been consistently emphasized, though the methods of promoting them vary widely. Ethics in public service refers to the standards of right conduct expected of government officials. These standards include honesty, impartiality, integrity and respect for the rights of citizens. In the United Kingdom, for example, the civil service code outlines clear values of impartiality, objectivity and commitment to public interest. The existence of such codes is important because it establishes a benchmark against which conduct can be judged. Yet codes alone are not enough. They must be backed by active training, institutional reinforcement and an environment where ethical conduct is recognized and rewarded.

Accountability complements ethics by providing mechanisms through which public officials are held responsible for their actions and decisions. Accountability operates on multiple levels: legal, political, administrative and professional. Legal accountability ensures that officials act within the boundaries of law, while political accountability links actions to elected representatives who must justify policies before citizens. Administrative accountability involves oversight by internal or external bodies such as auditors, inspectors, or ombudsmen. Professional accountability is maintained through codes of conduct enforced by professional associations. These overlapping systems create a web of responsibility, making it difficult for misconduct to go unnoticed or unchecked. However, challenges remain. In many contexts, accountability systems are weakened by political interference or lack of independence. For instance, when oversight agencies are dominated by partisan interests, they may fail to investigate corruption or malpractice effectively. Similarly, ethical standards may exist in law but lack enforcement in practice. This creates a situation where misconduct persists despite formal frameworks. Citizens observing such gaps may lose trust in institutions, viewing them as hypocritical or selfserving.

Transparency is a key component linking ethics and accountability. When administrative actions, budgets and decision-making processes are open to scrutiny, the likelihood of unethical behavior decreases. In the UK, freedom of information laws has empowered citizens and journalists to request government documents, thereby holding officials accountable. Similar mechanisms exist in France and Germany, where transparency in budgeting has increased citizen awareness of how resources are used. Transparency acts both as a preventive tool deterring misconduct and as a corrective tool enabling detection when problems occur. Whistleblower protection laws represent another important aspect. They provide employees with legal safeguards when reporting misconduct, corruption, or abuse of power. Without such protections, employees may fear retaliation and remain silent. The United States’ Whistleblower Protection Act, for example, has encouraged public servants to speak up against malpractices, contributing to accountability. Yet whistleblowing can also be controversial, as it may expose sensitive information or disrupt administrative processes. Balancing protection with responsibility is therefore a delicate but necessary task.

Ethics and accountability also intersect with the issue of corruption. Corruption erodes trust, distorts resource allocation and undermines fairness. Anti-corruption commissions and integrity units are established in many countries to combat this problem. In Singapore, the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau has built a reputation for independence and effectiveness, significantly reducing corruption levels over the decades. The success of such institutions rests not only on laws but also on political commitment and public support. Without consistent political will, anti-corruption measures often remain symbolic. Education and training play a vital role in instilling ethical values in public servants. Universities, professional schools and civil service academies increasingly incorporate ethics modules into their curricula. These programs expose students and trainees to real-life dilemmas, case studies and simulations, enabling them to think critically about their responsibilities. In the long run, building an ethical culture is more effective than relying solely on punitive measures. An organization where ethical conduct is celebrated and rewarded is less likely to experience systemic misconduct.

Globalization and digitalization have introduced new ethical challenges. The rise of social media means that public officials actions can be scrutinized in real time, often leading to reputational consequences before formal accountability mechanisms are activated. Digital governance also raises questions of data privacy, surveillance and cybersecurity. Officials must balance the efficiency of digital systems with the ethical obligation to protect citizen data. Failures in this area, such as large-scale data breaches, not only undermine trust but also expose governments to legal and financial liabilities. Cultural differences further shape how ethics and accountability are understood. In some societies, collective responsibility and harmony are prioritized, making accountability a shared rather than individual concept. In others, individual responsibility is emphasized, with officials personally answerable for decisions. Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Collective responsibility can dilute accountability if no single individual feels obligated, while excessive individual accountability can discourage risk-taking or innovation. Effective systems often balance both, ensuring that teams work together while individuals remain responsible for their roles.

Citation: Brown E (2025). Ethics and Accountability in Public Service Delivery. 13:489.

Copyright: © 2025 Brown E. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.