Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- ResearchBible

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2021) Volume 9, Issue 4

Comparison of Isometric Endurance of Abdominal and Back Extensor Muscles in Manual and Sedentary Males in the Age Group of 20-40 Years

AMR Suresh1*, Dimple Kashyap2, Tapas Priyaranjan Behera3 and Ebenezer Wilson Raj Kumar D42Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital, New Delhi, India

3Department of Prosthetics and Orthotics, Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay National Institute for the Persons with Physical Disabilities (Divyangjan), New Delhi, India

4Department of Occupational herapy, Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay National Institute for the Persons with Physical Disabilities (Divyangjan), New Delhi, India

Received: 21-Jun-2021 Published: 14-Jul-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2329-8847.21.9.254

Abstract

Background: Stabilization of trunk flexors and extensors are essential for normal lumbo-pelvic function. These muscles, known as “core muscles”, have a basic role in balance and coordination in sitting. The core is the lumbopelvic- hip complex which includes lumbar spine, pelvis, hips, and their respective musculature. Pattern of core activity changes in sitting and dysfunction of core muscles increased the risk of damage of the upper and lower extremities segments. Powerful core muscles support stabilizes the vertebra and pelvis, prevents balance disorder and decreases the rate of LBP which is one of the most prevalent occupational disorders. Endurance of trunk muscles depends on the life style and working condition of individuals. Imbalance in the trunk muscle endurance secondarily leads to back pain, which disables the person and reduces the functional capacity of individuals.

Objective: The aim of this study is to evaluate the difference in isometric endurance between abdominal and back extensor muscle in manual and sedentary workers and guide them about the importance of endurance training in preventing the back pain in the future.

Materials and methods: This study includes 40 simple randomly sampled normal male subjects according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the age group of 20-40 years, recruited on voluntary basis and allotted to Group A (N=20, Manual workers) and Group B (N=20, Sedentary workers). Modified Kraus weber’s test for abdominal muscles and Modified Sorensen’s test for back extensor muscles were performed by both Group A and Group B in two successive trials for each test with a rest break of 3-5 minutes in between the trials and the best of trials in seconds is recorded with a stop watch and the data is analyzed using SPSS statistics software version 19.

Results: The isometric abdominal muscles endurance is more in manual workers than the sedentary workers, at a significance level of p<0.005.The isometric endurance of back extensor muscles is more than isometric abdominal muscles in both the groups, at a significance level of p<0.005.The isometric back extensor muscles endurance is more in manual workers than in sedentary workers, at a significance level of p<0.005.

Conclusion: The isometric abdominal muscles endurance is less in both the groups as compared to isometric back extensor muscles endurance. So, abdominal muscles should be concentrated during endurance training. The objective of any fitness regime, maintenance of good health and posture and treatment of back pain is identifying dangerous causes that require immediate attention and attempt to prevent chronic low back pain problems. The modified Sorensen’s and Kraus Weber’s test can be used to asses and train the trunk muscles endurance as they are simple, easy, reliable and replace the costly and time consuming machine methods for evaluating and training endurance.

Keywords

Isometric; Endurance; Back extensors; Abdominals; Core strengthening; Trunk stability

Introduction

Modern life has pushed human societies toward sedentary lifestyles [1,2]. A sitting lifestyle may be one of the most critical public health problems in the 21st century [3]. Due to the lower center of gravity and a wider base of support, sitting is a comfortable posture imposing low energy consumption [4]. Likewise, performing daily activities in a sitting position contributes to a sedentary lifestyle.

Those individuals who do not have any physical activity are in the non-moving or sedentary group [5]. The activities of energy expenditure between 1.0-1.5 METS (Multiples of the basal metabolic rate) are classified as sedentary behaviors [6]. Light intensity activity behaviours require expenditure of no more than 2.9 METs. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity requires an energy expenditure of 3 to 8 METs. Medium to high level of activity are recommended for prevention and treatment of many chronic diseases [7]. A sedentary lifestyle increases the risk of musculoskeletal problems [5,6]. Maintaining the same position for extended periods may impose creep and deformation in soft tissues [8]; however, the duration of sustained positions to cause creep or deformation varies [9].

Stabilization of trunk flexors and extensors are essential for normal lumbopelvic function [10]. These muscles, known as “core muscles”, have a basic role in balance and coordination in sitting [11]. The core is the lumbopelvic-hip complex which includes lumbar spine, pelvis, hips, and their respective musculature. On the other hand, core stability is critical for trunk and extremities movements as well [12]. Pattern of core activity changes in sitting [13,14] and dysfunction of core muscles increased the risk of damage of the upper and lower extremities segments [14]. Powerful core muscles support stabilizes the vertebra and pelvis, prevents balance disorders [11] and decreases the rate of LBP which is one of the most prevalent occupational disorders [15].

Stabilization of trunk flexors and extensors are essential for normal lumbopelvic function [10]. These muscles, known as “core muscles”, have a basic role in balance and coordination in sitting [11]. The core is the lumbopelvic-hip complex which includes lumbar spine, pelvis, hips, and their respective musculature. On the other hand, core stability is critical for trunk and extremities movements as well [12]. Pattern of core activity changes in sitting [13,14] and dysfunction of core muscles increased the risk of damage of the upper and lower extremities segments [14]. Powerful core muscles support stabilizes the vertebra and pelvis, prevents balance disorders [11] and decreases the rate of LBP which is one of the most prevalent occupational disorders [15].

The manual work is termed as “the work which needs continuous strenuous muscular efforts in which muscle has to work to its maximum strength and endurance. This work contains conditions like continuous standing, bending, rotation, lifting heavy weights etc.” In all activities of daily living and working conditions, there is soft tissue strain resulting from sustain statue posture like frequent lifting and twisting, prolonged sitting in one position [19-21].

Back and abdominal muscle shows continuous activity during standing, lifting, rotation, twisting [22], However while sitting, there is very minimal or no activity [13]. So, to protect the soft tissue strain and to sustain the posture, these muscles must have proper endurance. There is normal ratio of abdominal and back extensor endurance in normal individuals [21]. But, because of the working conditions and type of work there is difference in the abdominal and back muscle endurance in manual and sedentary workers.

A change in the muscle endurance performance leads to back pain and disability [23-27]. Several studies investigating the relationship between muscle endurance, back pain, and disability caused by this has already been done. Endurance of trunk muscles depends on the life style and working condition of individuals. Imbalance in the trunk muscle endurance secondarily leads to back pain, which disables the person and reduces the functional capacity of individuals. So, the objective of this study is to evaluate the difference in isometric endurance between abdominal and back extensor muscle in manual and sedentary workers and guide them about the importance of endurance training in preventing the back pain in the future.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

Experimental study design with 40 healthy male participants, who reported as attendants to the ongoing treatment of their family members at Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay national institute for the persons with physical disabilities (Divyangjan), New Delhi, India within the age group of 20-40 years were recruited on voluntary basis and informed consent was obtained before the study and the participants were allotted to groups, Group A (20 Manual workers) and Group B (20 Sedentary workers). The inclusion criteria was individuals working in the said capacity for 3-5 years, manual workers who do manual work in continuous standing position for more than 4 hours per day and at least 5 days a week and sedentary workers who do office work involving sitting for more than 4 hours per day and at least 5 days a week. The exclusion criteria was history of back pain in the last 1 year, abdominal/gastric issues, any neurological, cardiac, orthopedic and pulmonary diseases and any other disease that may interfere with the assessment.

Equipment’s used

Stopwatch

Pillows and Towel rolls.

Plinth and stabilizing straps

Procedure

The subjects included in this study were taken into confidence and good rapport was developed with each of them. The procedure was explained and demonstrated to each one of them. When procedure was well understood by each of them, the following tests were performed by both Group A and Group B and in two trials for abdominal muscles and back extensor muscles with a rest break of 3-5 minutes in between and the best of two trials is recorded for data analysis.

Parameters studied

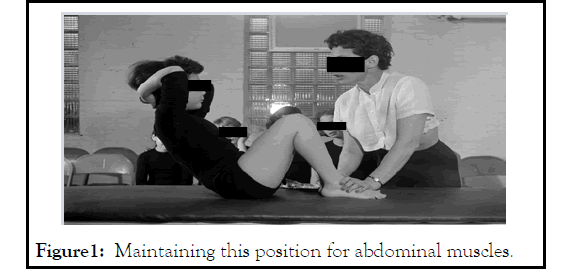

Modified Kraus weber’s test (For abdominal muscles): Subject is in supine lying with hip and knee in 90º of flexion. Arm behind the head to support and maintain the neck in flexion without any undue discomfort. The subject is asked to do a curl up and hold the position midway between crook lying and crook sitting when ready, time taken in holding/ maintaining this position is recorded with a stop watch (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Maintaining this position for abdominal muscles.

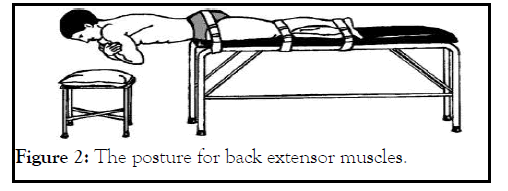

Modified Sorensen’s test (For back extensor muscles): Subject lying prone with the trunk off the plinth with towel roll/ pillow support under the pelvis and legs to avoid pressure pain and after making the subject comfortable, strapping is done to secure the position of the subject and a stool with soft padding is placed in front of the plinth for hands to land during the termination of the test or for emergency stoppage of the test, the subject is asked to maintain steady horizontal state when ready and time taken in holding/ maintaining this position is recorded with the help of stopwatch (Figure 2) [28,29].

Figure 2: The posture for back extensor muscles.

Protocol followed

During the above procedure the subjects were asked to maintain cervical flexion and pelvic stabilization through gluteal muscle contraction. The cervical and pelvic alignment proved to be the most optimal posture not only for decreasing lumbar lordosis but also activating trunk flexors and extensors.

Subjects are advised to avoid Valsalva maneuver during this test.

The criteria for the termination of the tests are pain and fatigue.

The holding time is recorded in seconds with the help of stopwatch.

Data collected and analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics software Version 19 to measure the statistical values of static endurance between abdominal muscles and back extensor muscles in manual and sedentary workers.

Statistical analysis

Individual’s characteristics are presented as means ± standard deviations. The unpaired t-test using SPSSsoftware verson 19.0 with a two-tailed significance with p-value of <0.005 (Table 1) (Figures 2-5).

| Group-A | Age (Years) | Isometric endurance | Mean (Sec) | S.D. | Diff (Sec) | t-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

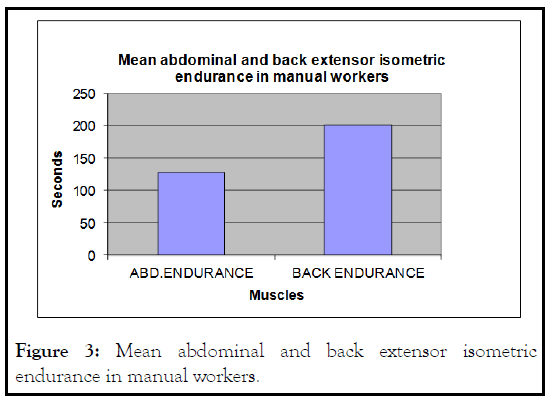

| Manual workers | 20-40 (30 ± 6.37) | Abdominal muscles | 128.5 | 15.7 | 73.15 | -0.005 | Significant |

| Back extensor muscles | 201.65 | 55.72 | 5.19 (E-06) |

Table 1: Difference of isometric abdominal muscles and back extensor muscles in manual workers.

Figure 3: Mean abdominal and back extensor isometric endurance in manual workers.

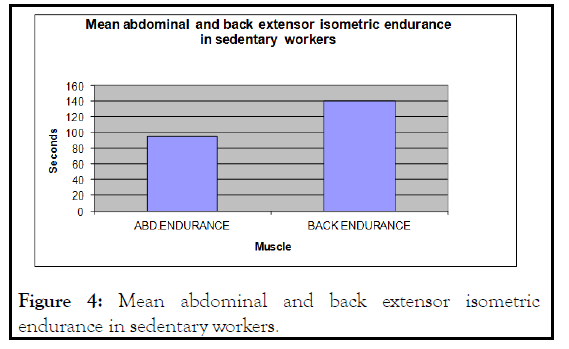

Figure 4: Mean abdominal and back extensor isometric endurance in sedentary workers.

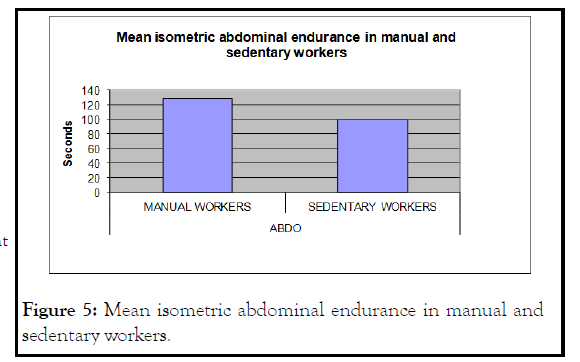

Figure 5: Mean isometric abdominal endurance in manual and sedentary workers.

The mean and SD of isometric abdominal muscles endurance is (128.5 ± 15.70) seconds. The mean and SD of isometric back extensor muscles of spine endurance is (201.65 ± 55.72) seconds. The difference of endurance between isometric abdominal muscles and isometric back extensor muscle of spine is 73.15 seconds which shows that endurance of isometric back extensor of spine is more than endurance of isometric abdominal muscles (Table 2).

| Group-B | Age (Years) | Isometric endurance | Mean (Sec.) | S.D. | Diff. (Sec.) | t-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary workers | 20-40 (30 ± 6.37) | Abdominal muscles | 94.44 | 21.72 | 46.17 | -0.005 | Significant |

| Back extensor muscles | 140.61 | 22.69 | 2.94 (E-06) |

Table 2: Difference of isometric abdominal muscles and back extensor muscles in sedentary workers.

Unpaired t-test, comparing the significance with t-value of 5.19 (E-06) is highly significant at p<0.005 level.

The mean and SD of isometric abdominal muscles endurance is (94.44 ± 21.72) seconds. The mean and SD of isometric back extensor muscles of spine endurance is (140.61 ± 22.69) seconds. The difference between isometric abdominal muscle endurance and isometric back extensor muscle endurance in sedentary workers is 46.17 sec, which shows that the endurance of back extensors muscles is more than abdominal muscles in sedentary workers.

Unpaired t-test comparing the significance with t-value of 2.94 (E-06) is highly significant at p<0.005 level (Table 3) (Figure 4).

| Abdominal muscles | Groups | Age (years) | Mean (Sec.) | S.D. | Diff (Sec.) | t-value | |

| Manual workers | 20-40 (30 ± 6.37) | 128.5 | 16.84 | 29.1 | 3.76 (E-05) | Significant | |

| Sedentary workers | 20-40 (28.1 ± 5.3) | 99.4 | 26.56 |

Table 3: Difference of isometric abdominal muscles in manual workers and sedentary workers.

The mean and SD of isometric abdominal muscles endurance in manual workers is (128.5 ± 16.84) seconds. The mean and SD of isometric abdominal muscles endurance sedentary worker is (99.44 ± 26.56) seconds. The difference of isometric abdominal muscle endurance between manual and sedentary workers is 29.1 seconds which shows that the isometric endurance of abdominal muscles is more in manual workers than sedentary workers.

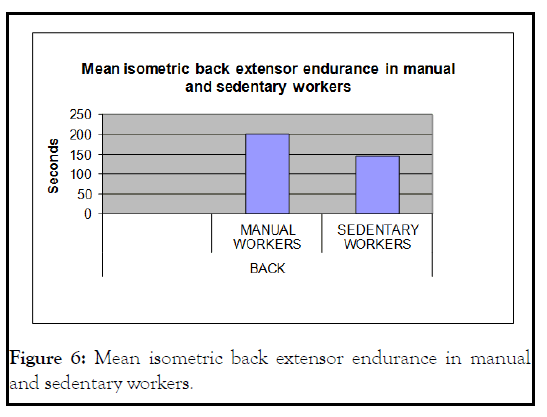

Unpaired t-test comparing the significance with t-value of 3.76 (E-05) is highly significant at p<0.005 level (Table 4) (Figure 6).

| Back extensor muscles | Groups | Age (years) | Mean (Sec.) | S.D. | Diff (Sec.) | t-value | |

| Manual workers | 20-40 (30 ± 6.37) | 202.35 | 60.03 | 58.59 | 4.65 ( E-05) | Significant | |

| Sedentary workers | 20-40 (28.1 ± 5.3) | 143.76 | 23.86 |

Table 4: Difference of isometric back extensor muscles in manual workers and sedentary workers.

Figure 6: Mean isometric back extensor endurance in manual and sedentary workers.

Results and Discussion

The isometric abdominal muscles endurance is more in manual workers than the sedentary workers, at a significance level of p<0.005.

The isometric endurance of back extensor muscles is more than isometric abdominal muscles in both the groups, at a significance level of p<0.005.

The isometric back extensor muscles endurance is more in manual workers than in sedentary workers, at a significance level of p<0.005.

Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 2 and 3 shows that the endurance of isometric back extensor muscle is more than the isometric endurance of abdominal muscles in both groups and it is highly significant. During manual work, generally there is activity of both abdominal muscles and back extensor muscles. But, back extensor muscles are postural muscles, so they act continuously and maximally with recruitment of all fibers. While abdominal muscles act very minimally during this situation and maximally in strainous work during manual work [29-31].

Liebenson suggested that modern sedentary life style has an impact on the development of muscular dysfunction. A tendency is seen towards overuse of postural muscles because of prolonged constrained postures during sitting. Phasic muscles on the other hand tend to become inhibited and weak, because of disuse and de-conditioning. Modern societies emphasize on constrained postures and sedentary lifestyle promotes an imbalance between overactive and inhibited muscles. Also in sedentary work, there is no activity of abdominal muscles seen as compare to spinal extensor muscles there is no recruitment of fibers seen in abdominal muscles. Because of disuse of abdominal muscles, the antagonistic back muscles become stronger by overuse. Thus, there is protrusion of abdomen with compensated lumbar lordosis is seen in sedentary workers.

Table 3 and Figure 4 shows that isometric abdominal muscle endurance is more in manual workers than in sedentary workers. This may be due to strainous activities in manual work, there is more number of fibers recruitment as there is more activity of abdominal muscles to increase in intra-abdominal pressure to stabilize the spine and abdominal contents (spatially inguinal canal). So, their endurance will be more. But, in sedentary work, there is no or very minimal activity of abdominal muscles. So, its endurance will be decreased [32].

Table 4 and Figure 5 shows that endurance of isometric back extensor muscles is more in manual workers than sedentary workers. In manual work, there is more number of recruitment of muscle fibers seen because of strainous activity (as back muscles acts more as tonic i.e. postural muscles as well as work to bear extra load). In this, there is recruitment of type-I and type-IIa and IIb muscles seen. So, its endurance will be more. However, in sedentary work, back extensor muscles acts only as tonic muscles. Also, there is no recruitment of extra number of muscle fibers as there is no extra load to recruit them. So, its endurance will be less as compare to manual workers.

Low back pain is a well-recognized major cause of disability in the industrialized world with multi factorial etiology. Spine endurance and stabilization exercises are most commonly prescribed by professionals for the rehabilitation and prevention of low back injuries. Diminished trunk extensor muscle endurance is linked to low back trouble as endurance plays a significant role in back health rather than strength which has a very weak relationship with back health in normal subjects. These mean scores and ratios can be used as a guideline to recognize muscle dysfunction and also to anticipate low back pain occurrence in the future.

The lumber stability is obtained through both the concomitant increase in muscle co-activation of back extensor muscles and abdominal muscle s and for this both muscles groups needs good endurance. An imbalance in trunk muscle endurance can influence significant lordotic curve of lumbar spine and might be one of the risk factor for potential low back pain. Endurance of both muscles groups is important to maintain the stability of spine, restore the function and prevent the disability due to back pain.

Conclusion

The isometric abdominal muscles endurance is less in both the groups as compare to isometric back extensor muscles endurance. So, abdominal muscles should be concentrated during endurance training. The objective of any fitness regime, maintenance of good health and posture and treatment of back pain is identifying dangerous causes that require immediate attention and attempt to prevent chronic low back pain problems. The modified Sorensen and Kraus Weber test can be used to asses and train the trunk muscles endurance as they are simple, easy, reliable and replace the costly and time consuming machine methods for evaluating and training endurance and can be performed anywhere and also without spatial supervision.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

As the modified Sorensen and Kraus Weber test for evaluating the isometric endurance of back extensor and abdominal muscles are simple, easy to perform and reliable, they can be used as preventive measure for low back pain and disability associated with them. Persons with age group more than 40 years could be studied with more number of male and female subjects to further validate the findings of the study. The effectiveness of training may be found out by taking pre-training and post-training endurance values for the given training period. Age, gender, BMI, Personal habits, emotional status and diurnal variations all these factors has effect on endurance. So, all these factors can be taken into account while evaluating the endurance. Future studies can be conducted on subjects with sedentary lifestyle with and without low back pain in different BMI groups by employing ultrasound imaging techniques and exploring trunk muscle thickness.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the institution for providing an opportunity to work on the title of the study. The authors are grateful to the subjects that participated in the study. Special thanks go to Mr. Pradeep Marandi, Supdt. PT who managed the subjects and study environment for smooth conduction of our study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

Approved.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

- Egger GJ, Vogels N, Westerterp KR. Estimating historical changes in physical activity levels. Med J Aust. 2001;175(11-12): 635-636.

- Jans MP, Proper KI, Hildebrandt VH. Sedentary behavior in Dutch workers: differences between occupations and business sectors. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6): 450-454.

- Pauwels S, Wilmaerts J. Sedentary lifestyle and influence on trunk flexors and extensors muscle endurance among first year university students. 2017.

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9): S498-504.

- Ayanniyi O, Ukpai B, Adeniyi A. Differences in prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms among computer and non-computer users in a Nigerian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1): 177.

- Van Uffelen JG, Wong J, Chau JY, Ploeg HPV, Riphagen I, Gilson ND, et al. Occupational sitting and health risks: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4): 379-388.

- Chau JY, Van Der Ploeg HP, Van Uffelen JG, Wong J, Riphagen I, Healy G, et al. Are workplace interventions to reduce sitting effective? A systematic review. Prev Med. 2010;51(5): 352-326.

- Solomonow M, Baratta R, Zhou B-H, Burger E, Zieske A, Gedalia A. Muscular dysfunction elicited by creep of lumbar viscoelastic tissue. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2003;13(4): 381-396.

- Van Uffelen JG, Heesch KC, Brown W. Correlation of sitting time in working age Australian women: who should be targeted with interventions to decrease sitting time? J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(2): 270-287.

- Yoo W-G, An D-H. The relationship between the active cervical range of motion and changes in head and neck posture after continuous VDT work. Ind Health. 2009;47(2): 183-188.

- Maribo T, Schiottz-Christensen B, Jensen LD, Andersen NT, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Postural balance in low backpain patients: criterion-related validity of centre of pressure assessed on a portable force platform. Eur Spine J. 21(3): 425-431.

- Nesser TW, Huxel KC, Tincher JL, Okada T. The relationship between core stability and performance in division I football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(6): 1750-1754.

- Knežević O, Mirkov D. Trunk muscle activation patterns in subjects with low back pain. Vojnosanitetski pregled.military- Medical and pharmaceutical review. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70(315): 315-318.

- O’Sullivan PB, Grahamslaw KM, Kendell M, Lapenskie SC, Moller NE, Richards KV. The effect of different standing and sitting postures on trunk muscle activity in a pain-free population. Spine. 2002;27(11): 1238-1244.

- Johnson J. Functional rehabilitation of low back pain with core stabilizations exercises: suggestions for exercises and progressions in athletes, All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 2012.

- Janwantanakul P, Pensri P, Jiamjarasrangsi W, Sinsongsook T. Associations between prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms of the spine and biopsychosocial factors among office workers. J Occup Health. 2009;51(2): 114-122.

- Arab AM, Salavati M, Ebrahimi I, Mousavi EM. Sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of the clinical trunk muscle endurance tests in low back pain. Clin Rehabil. 2009;21(7): 640-647.

- Tissot F, Messing K, Stock S. Studying the relationship between low back pain and working postures among those who stand and those who sit most of the working day. Ergonomics. 52(11): 1402-1418.

- Gorden Waddell. The back pain revolution. 2004.

- Chok B, Lee R, Tan SB. Endurance training for the trunk extensor muscles in people with subacute low back pain. Phys Ther. 1999;79(11): 1032-1042.

- Moffroid MT. Endurance of trunk muscles in persons with chronic low back pain assessment, performance and training. ; J Rehabil Res Dev. 1997;34(4): 440-447.

- Moreau CE, Green BN. Isometric back extension endurance tests: A review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(2): 110-122.

- Brain P, Orazio D. Low back pain handbook. 1999.

- Moffroid MT, Haugh LD, Haig AJ, Henry SM, Pope MH. Endurance training of trunk extensor muscles. Phys Ther.1993;73(1): 3-10.

- Ito T, Suzuki H, Takahashi M, Kaneda K, Strax TE. Lumbar trunk muscle endurance testing: An inexpensive alternative to a machine for evaluation Achieves of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(1): 75-79.

- Keller TS, Roy AL. Posture dependant isometric trunk extension and flexion strength in normal male and female subjects. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15(4): 312-318.

- Craig Liebenson DC. The rationale for physical capacity tests. Dynamic chiropractic. 2000.

- Biering-Sorensen F. Physical measurements as risk indicators for low back trouble over a one year period. Spine. 1984;9(2): 106-119.

- Biering-Sorensen F. Medical, social and occupational history as risk indicators for low back trouble in a general population. Spine. 1986;11(7):720-725.

- Watson M, McElligott JG. Cerebellar nor-epinephrine depletion and impaired acquisition of specific motor tasks in rats. Brain Res. 1984;296(1): 129-138.

- Augustus White III, Manohar Panjabi: Clinical biomechanics of spine. 2020.

- Miller DJ. EMG study of lumbar paraspinal muscles of subjects with and without low back pain. Phys Ther. 1985;65(9): 1347-1354.

Citation: Suresh AMR, Kashyap D, Behera TP, Kumar WERD (2021) Comparison of Isometric Endurance of Abdominal and Back Extensor Muscles in Manual and Sedentary Males in the Age Group of 20-40 Years. J Aging Sci. 9: 254.

Copyright: © 2021 Suresh AMR, et al . This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.