Indexed In

- CiteFactor

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Scholarsteer

- Publons

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2016) Volume 4, Issue 1

An Assessment of Professional Ethics in Public Procurement Systems in Zimbabwe: Case of the State Procurement Board (2009-2013)

Abstract

This study seeks to assess the maintenance and promotion of professional ethics in the public procurement systems of Zimbabwe from 2009 to 2013. The information gathered reveal causal factors behind the violation of professional ethics. The Public Choice Theory propounded by Buchanan and the Principal-Agent Theory will help in explaining why such results have been attained. This paper was compiled after reviewing some procurement publications, journal articles, and newspapers as well as employing questionnaires and interviews. The research found that there is rampant and endemic violation of professional ethics in the Zimbabwean public procurement systems since the 1990s. About US$2 billion is believed to be lost due to financial indiscipline in 2012 only. This was because of a multiplicity of factors which acted as contributing factors for the thriving of corruption. Among these several factors include political predation, low remuneration levels as well as lack of knowledge which goes with the rigors of public procurement business. The study concludes that the determinants of unofficial practices are mainly due to political predation thereby impacting negatively on the economy. The study also makes some recommendations on how professional ethics could be fully maintained and promoted and such recommendations include decentralizing public procurement, national commitment towards rooting and stamping out graft, training of procurement officials, adopting e-commerce mechanisms and ensuring compliance to the code of conduct. The paper also notes the effects of financial indiscipline in the State Procurement Board. Zimbabwe’s public procurement systems if managed properly, would reduce skewed and uneven development, lure foreign investors and improve service discharge in the form of quality project implementation in the public sector.

Keywords: Professional ethics; Public procurement; State procurement board

Introduction

Since the year 2000, public sector enterprises in Zimbabwe have been faced with a plethora of challenges leading to poor service discharge. This stretched through 2008 although attempts have been made through public sector reforms. Corruption according to Tanzi [1] is a complex phenomenon that is almost never explained by a single cause. Causal factors leading to the violation of professional ethics in the public procurement can be traced back to the 1990s through 2000. According to Zhou [2], in the 1990s, the Zimbabwe government was embroiled in a matrix of socio-political problems. In this regard, lack of accountability, good governance and professional responsibility in state structures became endemic. Moyo [3], observes that from 2005, the RBZ turned public administration into a BACCOSSI affair without any policy accountability or professional responsibility. The appointee system was and still remains one of the causes compromising professional ethics. The President appoints the members of the SPB for a term of three years and thereafter may be re-appointed. According to Kunaka and Matsheza [4], the SPB is a statutory body whose members will be appointed directly by the president. In this regard, allegiance is one of the major stumbling blocks to professional ethics in the SPB.

Political appointees try to please their masters and in some cases ignore prescribed procedures. In support of this, Thebald [5], notes that under numerous pressures, often subject to extortion from their superiors to keep their jobs or having to bribe heavily in the first place to get them, corruption becomes inevitable. When the public procurement system is under the auspices of politicians, the entourage of the SPB end up being servants of political parties for they will be on a spotlight of political scrutiny, doing according to political demands thereby compromising professional ethics. Moyo [6], in this regard argues that corruption is inherent to the politics of patronage.

The palpable failure to maintain professional ethics can be attributed to political predation in the form of patronage system hence Derbyshire’s [7], argument that public administrators end up working within a political environment which in turn conditions their approach to work. They work reasonably close to political core face, constantly aware of political obligations and constrains. In this regard, procurement executives just do the job and there are reduced to a mere rubber stamp, a yes to political office bearers thus ignoring the required protocols of ethical and professional conduct.

In some cases, civil servants’ recruitments and promotions are less merit-based and appointments through a political ticket lead to employment without taking into consideration the credentials which suit the portfolio. In view of this, Moyo [3], argues that public workers are like doctors who diagnose first and then give proper prescription. The lack of adequate knowledge therefore led to inadequacy in market enquiry and the creation of an un-educational nature in the SPB. According to Machokoto [8], patronage system in the staffing process of appointment violate ethical and professional conducts as it is based on tribal, family and political ties. In cases associated with patronage, competence is set aside and nepotism is put at the forefront. The lack of professional ethics in this regard instils pressure on the civil servants to engage in unofficial practices.

In the same vein, according to Mupanduki [9], usually private companies grease high ranking officials in the procurement committee in order to be competitive which is a system of patronage based on who you know and who you are close to. Firms bribe government officials to avoid or reduce tax, to secure public procurement contracts, to bypass laws and regulations, or to block the entry of potential competitor (Ibid.p.197). Political corruption in line with this can be endemic as patronage politics breed opportunities for the annex of favouritism. As a result of professional protocols which are not always taken seriously, the concept of integrity can be defeated. Moyo [6], argues that operations in Zimbabwe depends largely on the management of informal relations and everyday life behaviours of individuals become more a function of informal than formal considerations which he further termed as normalising the abnormal.

Moreover, the excess prejudice of personalism also affects ethical and professional standards. This leads to personalities being taken into consideration instead of competitive values among suppliers. In concurrence with the above exposition, Moyo [6], notes that personalism does not allow for responsibility management based on well-defined principles of accountability. Excessive personalism in turn defeats the concepts of accountability and objectivity. In view of this, Machokoto [8], argues that this defeats important values like impartiality, proper execution of duty and honesty. Administration is often personalized as attitudinal orientations, particularistic rather than universalistic, ascriptive rather than achievement-focused (Ibid). This can threaten the viability of professional ethics thus Moyo [3], concludes that one of the reason why public administration in Zimbabwe today is dead is because of the personalization of public discourse as national issues become extensions of personalities and not technical or professional expressions of public policies.

Economic factors due to incapacity and financial constraints also had an adverse bearing on the professional conduct and ethics. In support of this, Machokoto [8], states that public servants of Zimbabwe appear to be unprofessional as a result of hardships, low remunerations and benefits. Remuneration of the civil servants is generally low compared to their counterparts in the private sector and the same can be said about their moral and ethical conduct. More so, the creation of the ZACC in 2011 to act as a watchdog against corrupt tendencies was welcomed by the populace as a final nail to unofficial activities but has been deliberately weakened through underfunding and understaffing. Andvig and Fjeldstad [10], note that the creation of institutions to prevent corruption are nothing but elements in a longterm process that needs to be supported from above and below and that also needs attitude changes at all levels. This implies that lack of political will multiply the ineffectiveness of institutions of integrity. In line with this, economic quagmire and weak institutions of integrity undermine professional ethics.

Psychological factors cannot be spared as a hindrance to ethical and professional standards. Maslow [11], classified this as the desire for prestige in the face of the world. This led to abuse of offices for material needs. Regardless of the state, employees somehow are tempted for human beings are generally perpetual wanting elements as they always want more. In support of this, Tanzi [1], notes that some of the bribes offered may be too large to resist. Corruption as a result of greed was further cemented in The Standard [12-15], when TI-Z chairman, Loughty Dube was quoted as saying corruption was not driven by poverty, “it is a matter of ethics, it does not need one to be poor to be corrupt … the high profile officials who are involved in corruption have millions of dollars in their bank accounts”. More so, most of public workers according to Moyo [3], practice moonlighting whereby they have a second informal job in addition to the main job. In line with this, a member of the SPB or relative of the member participating as a bidder in tender can also take part in the discussion of the proceedings of that tender which in turn defeats the whole purpose professional ethics in the tendering procedures.

Furthermore, failure by government to take timely and immediate action against those abusing power by failing to adhere to principles is also a challenge to professional ethics. According to Weber [12], this is lack of practical judgment due to red tape. Procedural wheels move at a slow pace due to the laborious processes of the structure. These bureaucratic channels slow the functionality of public service hence Moyo’s [6], argument that bureaucracy is not an engine for ethical and moral values. Corruption becomes inevitable due to excessive departmentalism and the SPB officials are left with no exit strategy except to clandestinely solicit for bribes from suppliers in order to quickly process their forms. Tambulasi [13], notes that bureaucracy slowly trek traditional public administration to the grave. In the case of urgent necessities, accessing funds from the SPB has been a challenge. Over and above, Matsheza and Kunaka [4], summarized causal factors, among others, as poverty, low salaries and economic uncertainty over one’s future. The case understudy is the SPB, a parastatal under the Zimbabwean financial services.

The SPB regulate the procurement of goods and services for the public sector. This national tender board has been set up to ensure fairness and transparency in the award of contracts for public works and supplies. Provision for the procurement of goods and services by the State in the Procurement Act [16] represent purchasing as a composite process with many offices, government departments and producers. In such a scenario, corruption is a problem that mainly arises in the nexus between the government and the market economy. This is because public procurement is one of the key areas where the public sector and the private sector interact financially. It is therefore a prime candidate and susceptible to cronyism, favouritism and bribery because of the magnitude and volumes of transactions.

As a result of financial indiscipline which has reached alarming levels, TI painted a gloomy picture on Zimbabwe as one of the most corrupt countries in the world. According to the 2009 to 2013 CPI [17], Zimbabwe ranges in-between 20-29 which is a third score from highly corrupt perceived levels of public sector corruption around the world, making the country the most corrupt in the SADC region (www.transparency.org.zw). This implies that Zimbabwe is not a corruption-free country. Due to this increase, Moyo [3], states that corruption has become so endemic in the public service to a point of becoming the norm.

The public procurement system has been marred by scandals, evidenced by the deterioration of ethical obligations and morality in the procurement business. Unethical practices by procurement staff in discharging their duties results in tenders seeming to swing towards political elites. A patron-driven political system favors the top leadership which leads to selective allocation of tenders thus threatening meritocracy and competence. The SPB is poorly constituted in terms of autonomy which results in parent ministers wielding extensive powers over tendering practices. Due to political predation, the board is often inclined to select suppliers without complying with the procurement regulations.

Despite invitation to tender notices being published in the government gazette, political interference in the determination of some tenders disregard established rules and is more prevalent in countries with greater state intervention in the form of regulation. This result in undue favouritism in the tendering practices as contracts are given to certain individuals on the basis of background rather than on competitive and cost-effective considerations. Personal interest and partisan politics are the main reasons for observed low accountability and transparency. In this regard, extended kinship and politics of patronage contribute to ineffectiveness and inefficiency.

In line with this, problems evolve in the tendering practices as rewards are offered for loyalty. When a loyal person is accused of corruption, the stalwarts of the ruling party immediately come to the defense of their protégé accusing those calling for accountability as sell out, racist, divisionist, tribalist, non-patriotic and anti the ruling party. Where the appointment of members is based on patronage, it may be difficult to penalize poor performance, which may be excused or tolerated rather than sanctioned. This in turn compromise transparency and accountability by protecting the corrupt in the public procurement systems. Due to lack of proper orientation on procurement, individuals end up becoming “institutions” themselves which is a major loophole that hampers effective procurement. Commissions of inquiry have been set to interrogate but failed to provide answers for million dollar questions like “Why it is happening like this?”, “What is wrong with employees?” “Do employees really understand the rules and regulations of their organizations?” and “What is the state of public procurement in Zimbabwe today?”

Literature Review and Theoretical Aspects of Professionalism

Literature review

Professional ethics is a field of applied ethics whose purpose is to define, clarify and criticize professional work and its typical values. It is a code of values and norms that actually guides practical decisions when they are made by professionals. In view of the above notion, Matsheza and Kunaka [18], view codes of conduct as a system of rules and regulations governing human behaviours in a particular environment. According to Amundsen and Andrade [19], ethics refer to principles which can be used to evaluate behaviour as right or wrong, good or bad. Ethics in this regard entail a system or set of moral principles and rules of conduct recognized in respect to a particular group or culture, that is, trust, respect, responsibility, accountability, fairness and honesty. Andrews [20], explains ethics as standards which guide the behaviour and action of personnel in all institutions regardless of type. Professionalism comprises principles and standards that guide behaviour in the world of business and failure to observe highest ethical values and standards constitutes a challenge. Professional ethics therefore represent what is permissible for practitioners as well as acceptable behaviours and norms that guide their activities despite the fact that institutions have different living and working structures and beliefs.

Professional ethics is a set of values whose purpose is to explicate the best possible world in which the given profession could be working. According to Amundsen and Andrade [19], ethics refer to well based standards of right and wrong, and prescribe what humans ought to do. Ethics are continuous efforts of striving to ensure that people, and the institutions they shape, live up to the standards that are reasonable and solidly based. They seek to provide a system of principles and procedures for determining what a person should do and should not do. From the foregoing, professional ethics define how things ought/ought not to be with respect to some issue, for instance, how a person should act. It is the assumption that what is good “ought to be” and, conversely, what is bad ought not to be. In line with this, professional ethics should be viewed through a normative lens rather than through the bureaucratic-democratic framework that has characterized much of the literature.

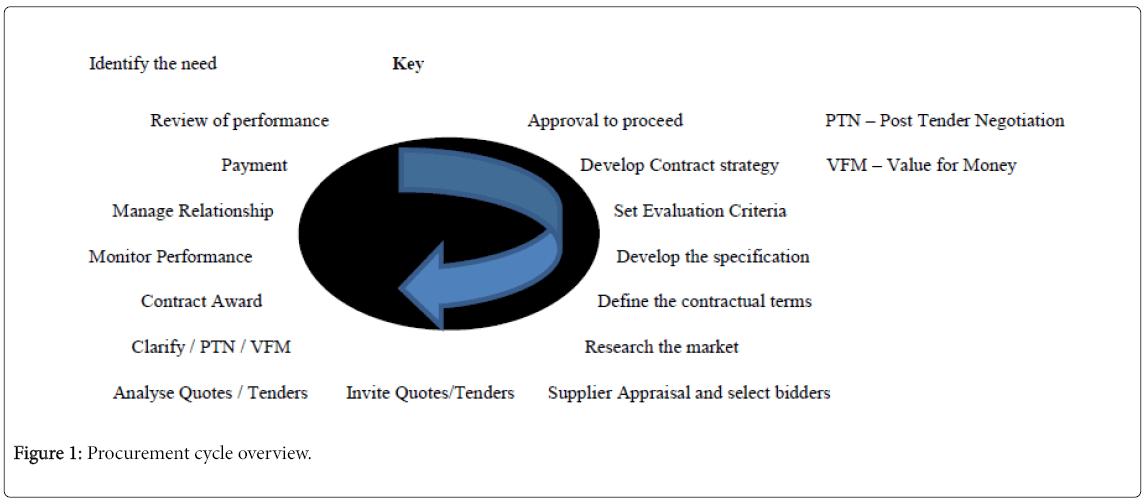

Public procurement system is a process where by the state entrust disbursing of public services to a public enterprise. According to Arrowsmith et al. [21], public procurement refers to the government’s activity of purchasing the goods and services which it needs to carry out its functions. There are three phases of the public procurement process; deciding which goods or services are to be bought and when (procurement planning); the process of placing a contract to acquire those goods or services which involves, in particular, choosing who is to be the contracting partner and the terms on which goods or services are to be provided; and the process of administering the contract to ensure effective performance (Ibid). In this regard, public procurement systems refer to the aforementioned trio. The phases can therefore be lumped into a single cohesive procurement cycle.

A point worth emphasizing is that, public procurement, unlike private, is a business process inside a form of government. Odhiambo and Kamau [22], broadly defined public procurement as the purchasing, hiring or obtaining by any other contractual means of goods, construction works and services by the public sector. The process of out-sourcing constitutes a method of privatisation which is referred to as contracting out. Public procurement therefore means procurement by a procuring entity using public funds. The items involved in public procurement range from simple goods and services such as cleaning services to large commercial projects, such as the development of infrastructure, including road, power stations and airports. Mupanduki [9], notes that such goods and services are often acquired through a public procurement process whereby the government entity contracts with a private sector enterprise to furnish a particular good or service for a fee subject to legal terms and conditions contained in a contract.

Musanzikwa [23], further defines procurement as a process of identifying, sourcing and purchasing of goods and services and covers all activities from identifying potential suppliers through delivery to the benefactors. Public procurement system according to Bovis [24], entails the process of sourcing goods and services destined for the public sector. Mamiro [25] stipulates that it can therefore be termed “public procurement” by virtue of using public funds. According to Odhiambo and Kamau [22], the composition of the entity called “public” poses a problem. While in some countries the term refers to the central and local governments only, it is extended in others to include government-owned enterprises providing public services, such as telecommunications, railways and water companies. Thus where it is not clearly specified, the term “public” may be used to refer to very different entities, which may not be comparable across countries.

Professional ethics constitute the nuts and bolts if not the veins and arteries of the whole procurement cycle. The breach of ethics in the public procurement systems has reached alarming levels. Issues of integrity and ethics in public procurement have been topical to the extent that hardly a day passes without a negative or positive report on the matter. The need for ethical and professional conduct in the public personnel administration therefore cannot be underestimated; it should be sensitive to the needs, aspirations and concerns of the public. Odhiambo and Kambau [22], note that efficient public procurement will not just come into being by itself for there are certain imperatives for the development of an effective procurement system, that is, improving work ethics in which public good is valued more than individual interests. Procurement officers are expected to be qualified and knowledgeable in an endeavour to ensure transparency, integrity, competence, accountability and honesty in fostering consistency and fair practices to ensure effective procurement.

Professional or personnel ethics refer to the organizational values and expectations which form the standard basis of behaviour and activity in the public personnel administration. Values are matters of ultimate ends of individuals or societies. An ethical value is therefore whatever is morally and ethically significant, right or wrong and valuable in the public sector. Professionalism, as a subset of ethics, refers to the guidelines and scientific principles of management to employees in an organization that can be used for instituting efficiency, order and stability. This implies that ethics and professional conduct are intertwined thus public personnel administration in procurement business cannot run away from professional ethics neither can it be separated.

Machokoto [8], observes that lack of professional ethics leads to poor attitudes by civil servants in handling issues. According to Matsheza and Kunaka [18], enabling environment for corruption include weak institutions of governance, that is, marginalization of other pillars by the executive branch. Corrupt activities become accepted as part and parcel of operational norms of institutions. This results in inadequate provision of services and supplies, forcing suppliers to be desperate to pay officials to access contracts. It is therefore a prerequisite for professional ethics to fill this lacuna of unofficial activities.

According to Kennedy and Malatesta [26], professional ethics commit members to serve the public interest; respect the constitution and laws; demonstrate personal integrity; promote ethical organizations; and strive for professional excellence. Financial indiscipline is intrinsically linked to the concept of ethics. It is thus pertinent to understand professional ethics within the context of corruption. Corruption behaviour is an act or state of being guilty of dishonest practices, pervasion of morality as well as integrity [18]. Professional ethics denote, among other things, accountability and transparency. Holtzhausen [27], therefore states that ethics are important in the administration of public activities as they serve as a cornerstone of transparency and accountability.

Public procurement in many countries is guided by the Procurement Act, that is, an Act of Parliament which prescribes procedures for the procurement of goods and services by the state. According to Arrowsmith et al. [21], regulatory rules on public procurement generally focus on the process of placing a contract to acquire goods or services. This is meant to ensure that procurement is effected in a manner that is transparent, fair, honest, cost-effective, and competitive. Mamiro [25] points that while incompetence among procurement executives have been indicated as of the deterrent factors, rigid procurement rules in Tanzania further complicate the constrains.

According to Zhou [28] political interference and abuse of parastatals as patronage dispensing instruments contribute to inefficiency and ineffectiveness. Politicians behave like people in a marketplace. Huntington [29], quoted in Andvig and Fjeldstad [10], states that where political opportunities are scarce, corruption occurs as people use wealth to buy power, and where economic opportunities are few, corruption occurs when political power is used to pursue wealth. This would explain the manner in which most tenders swing towards a particular class of people. Such a scenario is an affront to the principles of accountability and transparency. In some cases, board members of procurement entities are political appointees rather than professional technocrats.

In this regard, there is high probability of patronization of procurement institutions which in turn deter good governance in procurement business. Chitiyo [30] postulates that a number of key institutions, mainly in developing countries, were and still are, ‘policed’ by the military personnel. The security sector therefore undermines procurement by subverting civilian control over key organs of the state.

The current empowerment waves across Africa, for instance, Nigeria and South Africa has meant that very few people from ruling political parties have been benefitting from government programmes and tender processes on behalf of others. Taking the foregoing appraisals into cognisance, professional ethics like accountability and nondiscrimination in the public procurement system are undermined. This is affirmative in developing countries and it is more prevalent and inherent in the revolutionary ruling parties which are on the record of using patron-client system through appointments to managerial posts in public enterprises and statutory boards.

The need to comply with these ownership schemes has resulted in tenders being awarded to incompetent companies. Some tenders if not all, won by foreign owned companies have been invalidated in a bid to compliment with the ownership schemes. Contracts as result seem to be influenced decisively by high ranking officials. In a particular vein, Tambulasi [13] argues that political manipulation disrupt accountability structures and open avenues to corruption. This entails nepotism which Matsheza and Kunaka [18], define as the showing of special favours to one’s relatives as against other competitors in areas such as appointments and securing of contracts.

Hyden and Venter [31], observe that African civil servants are obliged to share the proceeds of their public offices with their relatives and more people secure jobs through personal contacts than through advertisements. The publication of invitation to tenders in an endeavour to widen the horizons of circulation is just but a mere formalization of the tendering proceedings. In line with the above, economy of affection can be injected, that is, connections or ties of blood, kin, community, or other affinities like familial or religious as determining public administration in Africa (Ibid).

Public procurement business is carried out in different ways in different countries. According to Odhiambo and Kamau [22], public procurement lessons from case studies like Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda reveal an increasingly important issue related to public procurement as whether governments discriminate in favour of domestic suppliers and the participation of the SMMEs as suppliers to the government. Consideration of professional ethics in public procurement systems however proved to be emblematic since mid-1980s in these aforementioned East African countries. In the case of Tanzania, the quest to ensure efficient, non-corrupt and transparent procurement led the government to review its procurement laws that were enacted in 2006, evidenced by the draft of national public procurement policy by the Ministry of Finance in 2012.

On the other hand, The Newsday [32,33], points that procurement in developed economies are a strategic profession that plays a central role in preventing mismanagement and minimising the potential of corruption in the use of public funds. Due to the intricate nature of public procurement, countries like Canada, France and Tanzania adapted electronic platforms similar to e-commerce for public procurement in an effort to dematerialise. Also in 2001, Japanese tendering systems for public works have undergone reforms to establish procurement processes online. Facets of e-procurement include e-sharing of procurement news, e-advertising of tenders, esubmission of bids, e-evaluation and e-auction, e-contracting, epayments, e-communication, e-dispute resolution and e-checking and monitoring. Policy lessons which can be drawn from e-procurement include reduced transaction costs, increased compliances, and improved management of information, offer competitive prices, timely and efficient payment to suppliers.

Theoretical framework

The principal-agent theory: In the principal-agent theory, the principal is the top level government official and the agent is the government official designated to carry the task. Corruption and bad governance stem from asymmetric information and interest divergence between those who perform tasks (the agents) and those on whose behalf tasks are performed (the principals). Teorell [34], explains corruption as illicit behaviour among agents to be controlled by a principal through mechanisms of institutional design. Corruption can result from manipulation of authority and power by elites in political and administrative structures resulting in institutional corruption. The vast array of such activities are made up of exchanges during everyday interactions between low-level public officials and citizens; exchanges made within the bureaucratic hierarchy, such as various forms of embezzlement and procurement kickbacks and exchanges made in order to exert influence over political institutions. Corruption in this model entails policy set by the top political leadership in order to reward their support coalitions with private goods. Higher-ranking officials cover up lower-level corruption in exchange for a share of the pie of bribes paid at lower levels in which each law enforcer supposed to punish corrupt acts may be corruptible but at the same time depend on another potentially corruptible law-enforcer higher up in the hierarchy (Ibid.p.9-10).

The public choice theory: This theory suggests that that violation of professional ethics is a possibility because the state is not a neutral actor. Buchanan and Tollison [35] equates the behaviour of individual actors in the government sector with persons in their various capacities as voters, candidates for office, elected representatives, leaders or members of political parties and bureaucrats. This implies that public choice provides an exegesis of the behaviour of persons acting politically, whether voters, politicians or bureaucrats. Politicians do not necessarily act in the interest of the public but rather on their own interest regardless of its effects and implication on development. According to Buchanan [36], the theory therefore offers an exegesis of the complex institutional interactions that go on within the political sector with the public officials seeking to maximize their economic interest. Public choice theory thus depicts the involvement of the leadership, their associates, relatives and friends in corruption which has frustrated efforts towards building a corruption-free environment. In sum, patronage is in-built in the theory.

Methodology

The research mainly focuses on qualitative data collection methods.

A group of respondents who constitute key informants were selected using purposive sampling which is a technique of identifying people that can serve as key informants, giving inside information and discussing topics on the research agenda. Leadership of the SPB were used to have an in-depth understanding of the relationship between public sector and private suppliers.

Quota sampling was used on people who have been receiving services. The unstructured interviews were conducted among senior employees like directors of the SPB and members of the general public respectively. They were also used on clients who come to register to compete on the tendering proceedings. Documents and statutory instruments were reviewed in accordance with what is to be assessed and also provide information for data that was collected in the field. These include the SPB annual reports, government publications and the SPB minutes.

The collected data was presented in thematic approach and issues that answer similar research questions was brought together in small sub-headings. Thematic sub-headings were used by the researcher in data presentation which is a descriptive presentation of qualitative data. Secondary data was analysed through a content analysis. Crosscase analysis was used, which is based on an in-depth investigation of a single individual or a group thereby taking each responded as a case.

Research Findings and Analysis

The role of professional ethics in public procurement

Professional ethics improve public image, protect public funds and aids decision making. This involves out-sourcing cost effectively from authentic sources; ensuring timely delivery and buying in accordance with procurement regulations to ensure VFM. In the case of value which exceeds $300 000 000, the SPB invites tenders for such supply in accordance with the procedure for formal tenders [37], thus there is need for professionalism in contracting out large transactions as the nature of corruption is associated with big business.

Professional ethics also ensure maintenance of vital principles of integrity, that is, transparency and accountability in meeting the criteria for selecting tenders. As a result, governmental contracts can be effectuated in a manner that is transparent, fair, honest, costeffective, and competitive [38].

Procurement procedures

The process for tender application: This is the process of inviting tenders after the planning phase of specifying needs. Advertising is done in local and international channels with a deadline for the submission of tenders. Procurement Act Part IV (31) provides that invitation to suppliers to tender shall be published in the Gazette, where the procuring entity is the State; and in a newspaper, where the procuring entity is not the State. Nevertheless, application procedures are prone to manipulation. Information gathered by The Newsday [39], indicates that tenders to rehabilitate a 31 km stretch of Illitshe Road in Umguza, Matebeleland North Province by ZINARA were advertised as a cover up to conceal the corrupt activities after the contract had already been corruptly awarded without going to tender. In this regard, mere formalization of advertising compromises the processes for tender application.

The procedure for tender processing: This entails the evaluation process were the best tender is selected. In support of the above, Musanzikwa [23], notes that tender processing determines the actual quality, reliability and delivery of the goods and services. Tender processing involves the verification of the suppliers’ capability. In spite of this, information gathered by The Sunday Mail [40] and The Herald [41,42], reveals allegations of corruption during the bidding and adjudication processes. Companies that were earmarked to win the ZETDC bid, like Denallaire Technologies, Finmark Industries and PowerTel had been pre-determined by corrupt officials from both ZESA and the SPB as there were related parties. Procurement executives cited Dr Magaya, PowerTel Communications’ chief technology strategy expert, in the violation of procurement regulations. Their involvement compromised tender evaluation processes as the same company which was also an adjudicator was evaluating other competitors. Serious breach of ethics can be noted in this regard.

The process for tender allocation: Tender evaluation is followed by contract signing with the supplier and implementation with penalties for breach of contract as an integral feature of agreement. Procurement Act Part IV (34) provides for the eligibility of suppliers, that is, before awarding tenders, they must satisfy the procuring entity by possessing necessary professional and technical qualifications and competence to perform the procurement contract. They are other requirements, that is, taking into account that they have paid all taxes, duties and rates for which they are liable in their respective countries. This process is followed by evaluating the performance of the contract.

However, procurement officers can use their public power to extract bribes from suppliers and some individuals become middlemen in the allocation of tenders. Commenting on transparency, The Newsday [32,33], points that the tender process in Zimbabwe has become a hotbed for corruption where government officials responsible for the allocation of tenders, together with powerful politicians in the different lines ministries, have benefitted from kickbacks and bribery. Tender application, processing and allocation entails planning, that is, specification phase, advertising, evaluation, that is, verification, award, contract signing and implementation and evaluation of performance.

In interpreting the overview above Figure 1, the cycle can be categorized into four phases. Identifying the need, approval to proceed, developing contract strategy, setting evaluation strategy, developing the specification, defining the contractual terms, researching the market, supplier appraisal and selecting bidders can be lumped into planning phase. Inviting of quotes or tenders can be categorized into the advert section and closing of tender. In line with this, clarifying PTN/VFM and analyzing quotes or tender scan further categorized into the evaluation phase. Contract award can be dubbed as the process of signing a contract. Lastly, review of performance, payment, managing relationship and monitoring of performance boils down to the evaluation of performance phase.

Direct and indirect factors contributing to the violation of professional ethics in public procurement

Factors contributing to the violation of professional ethics in procurement include lack of planning, lack of education and knowledge of procurement skills, low remuneration levels for procurement workers as they are being underpaid and lack of motivation or demoralization. These factors in turn create a breeding ground for corruption.

The acts of corruption on the part of procurement officials are ignored, not easily discovered, or when discovered are penalized only mildly. Lack of effective institutional controls opens the doors for corruption. Regulations and authorizations included in the procurement processes give a kind of monopoly power to the officials who are mandated to authorize and inspect procurement activities. Unethical activities will result from procurement officers with a great amount of power and a good chance to extract bribes.

The principal officer of the SPB as an appointee has discretion over important decisions related to the determination, selection, litigation and provision of contracts. As a result of this discretion over decisions regarding public investment projects, public procurement spending can become more distorted by corruption. Public projects in some case provide safe grounds for corruption. Corruption is likely to be a major problem in the procurement practices characterised by a patronclientele system. In the case of political corruption, those who represent the state, that is, the president and parent ministers or their close relatives may use the procurement to pursue rent seeking and corrupt practices. The aforementioned factors leading to the violation of professional ethics rotate on the attempts made by individuals to get favorable decisions, paying bribes and exploiting close personal relations with public officials.

Government bureaucracy is much more vulnerable to corruption. Colonial legacy go a long way in explaining why some bureaucracies are much less corrupt than others. According to Mupanduki [9], closely related to the weakness of government institutions is the colonial legacy which is impacting on the extent of corruption in independent Zimbabwe. Furthermore, politically motivated hiring, patronage and nepotism contribute to the lack of moral standards and discipline in government institutions which is detrimental to professional ethics.

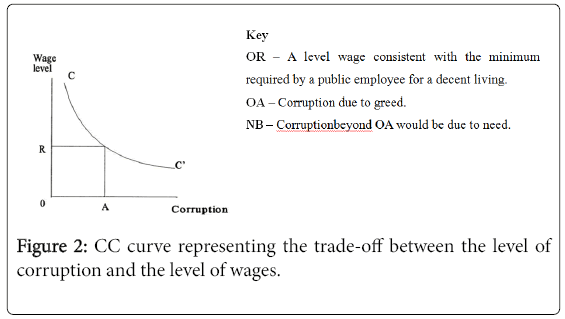

The incentive structures, that is, the level of public sector wages determine the degree of corruption. Though corruption results from greed or need, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs provides that for a worker to be motivated there must be recognition needs which include enough job resources. Absence of such needs lead to demoralization such that procurement officers cannot bother to trace mistakes in the process of procurement audit or can push procurement officers to resort to other means to make their ends meet. Tanzi [1], notes that the lower the wage level, the higher the corruption and vice versa. Procurement officers just as civil servants in Zimbabwe are earning low salaries; hence they are prone to soliciting or accepting bribes.

The relationship between wage level and corruption index as has been tested empirically in Figure 2 above means that a decrease in wage levels increases corruption. Low remuneration levels in turn results in poverty which can constitute a crime as procurement managers can be pushed to break the law by accepting bribes to make their ends meet. On the same note, increase in wages in an endeavor minimize corruption may worsen the situation as it may lead to demands for higher bribes by the corrupt officials. The rationale behind the aforementioned fact is that while the number of corrupt activities can be reduced, the total amount of financial indiscipline may not necessarily fall.

Institutional controls of corruption entail the first line of defence and the last line of attacking corrupt activities. A deeper look at the penalty systems constitutes a useful unit of analysis, especially for explaining the finer points which determine endemic corruption in the public procurement systems in Zimbabwe. Though the crime prevention institution of integrity in Zimbabwe plays a central role in deterring unethical acts to take place, it does not appear to provide a novel and auspicious direction for the fight against of corrupt activities. Higher penalties may worsen the situation as it may lead to demands for higher bribes by the corrupt officials.

Pragmatically, in Zimbabwe, few people are punished for acts of corruption. Moyo [3], notes that Zimbabwe suffers from an acute case of inability to implement what has been formulated. This is because political impediments prevent the full or quick application of the penalties thus implying politically motivated acts of corruption.

The challenges faced in the public procurement systems

The period of GNU was engulfed in a matrix of political tussles. Incessant changes within government commonly arise particularly in Africa and result in non-compliance to payment terms and failure to address potential conflicts of interest in public procurement [43].

In the case of low turnover in the execution of interventions, delays in decision making constitute a challenge in public procurement, emblematic in Gokwe North $600 000 hospital project lagging behind the plan for its completion. The Sunday Mail [40], indicates that the SPB has mainly been blamed for stretching the approval process for tenders to carry out government projects. For example, in 2012, the SPB contractor to build ZIMRA personnel living quarters at Beitbridge border post had failed to complete the work and attempts to give work to another supplier were discouraged by the SPB. In the same vein, The Newsday [44], unveils that REA equipment lies idle since the inception of the intervention in 1999 and “…the speed to channel money towards projects was hampered by the turnaround time, taking almost half a year to acquire materials through the SPB …” According to The Zimbabwean [45]. REA has brought power and light to a mere 10% of rural areas countrywide. In the same vein, information gathered by The Sunday Mail [46], indicates that, out of targeted 800 000 households, an approximate of 350 000-360 000 pre-paid meters have been installed thus low quality in project implementation.

In case of incompetence and financial indiscipline, it can be noted that that most individuals tasked with the responsibility to procure resources lack procurement skills. Financial indiscipline is a major challenge in public procurement due to lack of professional ethics. An interplay tenders have been marred with flaws and below are a capsule of some telling examples. According to Musanzikwa [23], the SPB has been accused of awarding tenders to shady and incompetent companies that offered them kickbacks, for instance, Harare City Council made a delivery of poisonous sodium cyanide, instead of aluminium sulphate solution, to Harare’s Morton Jeffrey Waterworks in September 2012.

In line with poor assessment of the market, it can be revealed that the deal to construct the Airport road was opaque and riddled with overpricing and over-procurement that is, purchasing at inflated prices. Frightening questions can be raised on why Dr Mahachi sticks to the view that council had no choice but to deal with Augur Investments as if there were no other alternative contractors. The tender for the construction of the 20 km road was pegged at a cost of $80 million. However, as indicated in The Sunday Mail [46], the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructural Development concurred with the Comptroller General financial year ended December 2010 in revealing that the cost of constructing a road should not exceed US $500 000 per kilometre. This entails that the monetary value cost of constructing the road should have been $10 million or so.

Due to political predation and interference, Airport Road tender to Augur Investments was awarded without going through an open tender process. This resulted in Augur Investments sub-contracting power construction of South Africa to enter upon the project because the tender was awarded on political grounds without taking into cognisance the capabilities of the company. This implies that process for tender awarding may spill into the political domain which in turn compromises efficiency. The more often procurement is channelled through political processes the awarding of tenders can be handicapped by the role of irrational political forces. In this regard, public procurement can be prone to individualism which is subject to favouritism.

The professional ethics-legislative framework Nexus

Lack of checks on the indigenization law compromises VFM. Moyo [3] points out that there is no doubt about the virtues of indigenization pronouncement but questions abound about its implementation design from a public administration point of view, especially with regards to its beneficiaries. The call for compliance with indigenization policy has resulted in tenders being allocated to companies without taking into account their competence. Musanzikwa [23] notes that 10% of the SPB tenders should be awarded to locally owned companies. The Herald [41,42], also reveals that Section 12 of Statutory Instrument 21-2010 as amended in March requires all public institutions to procure at least 50% of goods from indigenous suppliers. The policy is connected to the preferential awarding of tenders to companies with abilities to function properly but resulted in the creation of a fertile ground for corruption in the allocation processes since there are no clear checks and balances to monitor the processing of allocating tenders to locals.

The Procurement Act Part IV (41) provides that the SPB may declare a supplier ineligible to be awarded state contract. However, The Sunday [40], exposed allegations of deep-seated corruption and favouritism as the indigenisation law is not closely monitored. According to the General Laws Amendment Bill [47], the current empowerment wave has meant that very few Zimbabweans from one political party have been benefitting from government programmes and tender processes at the expense of Zimbabweans. Taking the foregoing appraisals into cognisance, accountability and nondiscrimination in the public procurement system is undermined. This is affirmative in developing countries, though it is more prevalent and inherent in the Zimbabwean ruling party which is on the record of using patron-client system through appointments to managerial posts in public enterprises and statutory boards.

The Standard [14] and The Standard [15], point that many avenues of looting have been created like ownership schemes. The Zimbabwean Government created NIEEB, a board is responsible for the disbursement of the CSOS. In this regard, procurement is embedded with patronage politics which in turn leads to skewed and uneven tender allocation as political predation undermines equal opportunity for all perspective bidders. This in turn raises alarming calls for ethical allocation of contracts in the public sector.

Special informal tenders are when the formal tender fails to bring up bidders thus it is used in circumstances mainly for national security matters [37]. It is worth appreciating that special formal tenders are faster than the formal tender. In Zimbabwe; this is emblematic in revelations by the executive chairperson of the SPB, Charles Kuwaza, that the President R.G Mugabe directed the awarding of the job to construct the NDC in Mazowe without going to tender. Nevertheless, despite national security concerns, they are allegations that President Mugabe directed the SPB to map out potential suppliers, sacrificing procurement regulations at the altar of politics.

The need to comply and follow the government’s much touted “Look East Policy” in the media led the SPB to follow instructions without going to tender. According to Zhou and Zvoushe [48], due to Look East, policy making is highly unpredictable, temperamental, exclusive, top-down and short-range in focus and characterized by what can be described as ‘implement first’ and ‘formulate and adopt later’. Moyo [3], further notes that what Look East Policy is in design terms remains fuzzy from a public administration point of view. Political predation is at play in dealing with the Chinese contractors.

The effects of violation of professional ethics on the Zimbabwean economy

Violation of professional ethics results in inefficiency-expensive/ non-compliant products, corruption, collusion and bribery. Flawed tenders prejudice government projects and the fiscus. According to The Standard [14,15], ZIMRA Commissioner General G.T. Pasi estimates that the country lost about US$2 billion to corruption in 2012. Poor service delivery is the order of the day as Zimbabwe is characterized by highest levels of corruption and lowest levels of service discharge. As a result of unethical activities, projects are either cancelled, not finished or half-done. This was also emblematic in the rehabilitation of Illitshe Road as information gathered by The Newsday [39], indicates that funds were released before the conclusion of tender procedures. Corrupt activities in turn led to the failure of the project.

Lack of professional ethics compromises economic transformation. The Newsday [49], indicates that without the political will to tackle corruption head-on, the much heralded ZimAsset is as good as dead in the water and Zimbabwe will plunge into a banana republic whose economy is solely dependent on one fluctuating export whose price is determined elsewhere. More so, prospects of democracy can be reduced. In transitional economies like Zimbabwe, corruption slows down or even blocks the movement toward democracy therefore reduce economic growth. Violation of professional ethics in Zimbabwe deter investors, for instance, the disappearance of the bid documents for the telephone digitalization project culminated in the withdrawal of a Japanese investor. If this negative perception continues, then efforts into universal aspirations like MDGs will face bottlenecks and development potential will never be realised.

The indigenization policy is acting as a grand deterrence to the achievement of VFM principle due to substandard and inferior materials and the inappropriate awarding of tenders associated with discrimination. It is also furthering the prevalence of sole sourcing in the awarding of contracts. The law currently stands as a collective ownership similar to state capitalism. As a result of financial indiscipline which has reached alarming levels, TI painted a gloomy picture on Zimbabwe as one of the most corrupt countries in the world as illustrated in APPENDIX D and E.

Comparative analysis with experiences from other countries

The Zimbabwean public procurement system, like Ghana, Tunisia and the UK, must take a departure from Stone Age and adopt space age waves of e-government in procurement. In The Newsday [39], President Mugabe blames corruption on the lack of moral standards. Like in other countries, for example, Tanzania and Uganda, procurement audits must be undertaken annually and procurement laws to be accompanied by contingency plans. Like in Botswana, compliance with the Code of Conduct must be emphasized and the Zimbabwean Government like in Zambia must cut bid bureaucracy to reduce tender processing time. Prosecution of wrong doers, employees manning and improving skills must be further emphasized.

The role of the state in fighting corruption in the procurement systems cannot be underestimated considering the creation of the ZACC in 2011 to curb graft in the public offices and TI-Z which has established a platform to enable the public to report cases of corruption.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

These are intuitive assessments reached after consideration of findings based on illustrations. Advisable strategies and possible courses of action in ensuring professional ethics and managing corruption in public procurement systems can also be proffered. The endeavour is to safeguard objectives of public procurement systems, that is, VFM, integrity, accountability, equal opportunities, fair treatment of suppliers, efficient implementation of policies in procurement and efficiency in the procurement processes.

The research concludes that public procurement systems in Zimbabwe seem to be lagging behind. The research further concludes that there is rampant infraction of professional ethics in the public procurement systems in Zimbabwe. It can also be concluded that determinants of informal public procurement in Zimbabwe leading to the irreverence of professional ethics are diverse; ranging from poor incentive structures to political interference. It can also be concluded that the Principal-Agent and the Public Choice theories appear to provide a novel and auspicious direction for studying factors behind the violation of professional ethics. It can therefore be concluded that there are useful units of analysis, especially for explaining the finer points which discourage the promotion and maintenance of professional ethics.

The study concludes that the Procurement Act [Chapter 22:14] is the footing for the management of public procurement business in Zimbabwe. It also concludes that policies like Indigenization and Look East are impacting negatively on the maintenance and promotion of professional ethics in the public procurement systems of Zimbabwe.

The study concludes that procurement is a common source and a safe ground of corruption. It also concludes that political elites influence public procurement decision making thereby compromising professional ethics. The study also concludes that professionalism has remained one of the cardinal ethics in the Zimbabwean public sector in general and public procurement to be specific but low wages has broken the commitment to discipline. The research also concludes that the ZRP-CIDF is giving a deaf ear to the matters of corruption. Cases are either ignored or not given proper attention by the police through what can be dubbed as “game of protection”. Less attention has been paid to those who might seek due process of law.

The study concludes that breach of professional ethics is impacting negatively on the economic growth of the country and endemic financial indiscipline is acting as a drawback to the smooth flow implementation of projects. It also concludes that violation of professional ethics constrains quality in the management of project implementation in Zimbabwe. Government might allocate enough and adequate inputs to speed up project implementation but the violation of professional ethics distorts the anticipated level of quality projects, programs, plans and policies. This resulted in handicapped products and poor service discharge and VFM can be lost in turn.

In the ultimate analysis, a plethora of challenges currently dogging public procurement in Zimbabwe includes tiresome processing of tenders, financial indiscipline and political predation. The gaps were attributed to weak institutions of integrity, pittance earnings of civil servants, loopholes associated with the appointee system of the Principal Officer and politics of patronage. Against this backdrop, violation of professional ethics in the procurement processes has rendered the procurement system ineffective and inefficient.

Unlike human beings whose death is for real and eternal, public procurement practices can be renewed and live again as if they had not died in the first place. With determined political will, corruption can be minimized, though not to zero. Realistically, the level will remain above zero for it is arduous for a country to be corrupt-free and none scores a perfect 10 in the CPI. Below are a capsule of the highlighted options or strategies and alternatives to fill in the gaps in the system. The following can therefore be made in this research.

Recommendations

The grand objective of public procurement must be centred on the principle of VFM which entails riddance of corruption. Important dimensions of VFM must be the first priority of all procurement executives. It is pertinent to ensure that laws provide emphatic guidelines of the rectification of faults to avoid contravention to the principle of VFM. Procurement awards must be reviewed to assess if it is in line with the procurement regulations.

Exposure of graft can help in dissuading corruption thus the exposé of the rot must be highly commended. The media acts as a watchdog thus can pose a blow on corruption. Media attention therefore would help as a deterrent, for procurement officials not to deviate from the radius of their prescribed procurement regulations. TI-Z must persist in acting as a whistle blower, providing warnings that there is abuse of power, secret dealings and bribery that continues to ravage the society of Zimbabwe to jolt government into action. When it comes to public spending, it must be publicized. The media may help in bringing unethical practices such as graft into light, thus in so doing it deters procurement practitioners from unethical conduct.

As it is arduous to suspend or scrap the policy, checks and balances must be established to guide the preferential clause on procurement to ensure transparency in the awarding of tenders. Going for low cost at the expense of foreign suppliers must be accompanied by proven capability of the supplier. Tenders should be given to deserving companies irrespective of nationality and political affiliation as the policy is not merely for political party cadres. Emphasis must be placed on the capabilities to carry out the contract on the agreed terms. In the same vein, non-compliant contractors who have failed in their obligations must be blacklisted to ensure that government departments do not use the same suppliers in future.

The SPB must adopt a decentralised system of procurement activities as a step towards professionalism like in the case of Zambia; to reduce multi-layered tender processing time; to mitigate bureaucratic nightmares and to ensure a speedier and shorter approval process. Each state spending agency should have some discretion to do their own procurement of materials instead of being constrained by going through the SPB which is characterized by delays, late commencement of procurements and prolonged evaluation processes.

Political will is very important in tackling graft head-on, taking a zero tolerance stance against graft. The political leadership of the country must openly campaign against corruption and denounce unethical conduct. There must be a governmental directive to provide stringent rules against illegal direct awards.

Knowledge of negotiation skills of procurement is essential. There is need for continuous professional development and training in the form of capacity building. Procurement seminars, workshops, conferences, symposiums and trainings, delivered by presenters with practical experience are paramount in capacitating procurement executives. Anyone to work in the purchasing department should have a CIPS qualification. The SPB must also make it mandatory for procurement executives to hold qualifications like SCM and IPL offered at CUT and other HNDs in Purchasing and Supply offered at polytechnics across the country. To combat moral decadence, education institutions must in still good moral values and discipline. Zimbabwe therefore needs to rebuild its moral fibre to create an environment that promotes accountability and transparency. Procurement executives must not merely confine themselves to public procurement skills but also gain skills to do with finance and contract and risk management.

There is a multiplicity of quintessential countries which represent the perfect example of quality online tender portals and mobile alert tender services, for example, UK, Tunisia, Tanzania, Ghana and the Asian Tigers. In order to ameliorate problems of corruption, a timeconsuming and laborious traditional tender process of paperwork, new technologies need to be adopted. The SPB must set up a website foreprocurement and e-participation to boost and improve the transparency of public purchasing at the same time reducing corruption in the tendering processes. It is worth emphasizing that prior to the installation of an e-procurement system, interplay of factors must be taken into account as the digital era has been accompanied by opportunities to misinform audiences. There must be thorough background checks of employees before placing them in positions of trust to screen out those with an appetite for crime. Companies must have water-tight measures in monitoring both incoming and outgoing e-mails so that any suspicious communication or transaction is investigated before unethical practices occur.

Politics must follow the supreme law of the land not law to follow politics. The government must tighten the screws of the law enforcing instruments to fight administrative corruption by increasing the penalties on those who get caught. The SPB must clarify rules and guidelines in all investment related decisions. The 2013 CPI indicates that stern rules governing the behaviour of those in public positions held Denmark and New Zealand to tie for the first place with scores of 91. In line with this foregoing appraisal, what is needful is a demonstration of the rule of enforcement so that individuals can be held accountable for their unofficial acts. Zimbabwe must strengthen institutions of integrity so that individuals will be afraid of the consequences of their actions. Like in the case of Kenyan Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, ZACC must be remodeled to include ethics.

Procurement cycle sometimes must be characterized by adjustments, modifications, increases/decreases, that is continuation of past government contractual activities with merely incremental changes to previous procurement decisions. Procurement wheels sometimes must not be reinvented. The SPB must not always start from scratch but consider up-to-date standardized documents to ensure consistency and reduce risk. Re-use of procurement sensible base documents and specifications if a solution has worked well in the past is important in lessening processing time. It is however important to check if past specification meet the needs, that is, adjusting in accordance with the prevailing circumstances to avoid “sunk cost”.

The rights and wrongs of procurement need to be emphatically defined to control corruption. Emphasis of compliance on ethics must be regarded as an important tool of promoting and upholding professional ethics. As in the case of Botswana and South Africa, the SPB must adapt and adopt King’s Code of Corporate Governance principles which include risk management, internal audit, information technology governance, compliance and enforcement. The SPB must establish an effective and independent audit committee. In line with King’s Code of Governance, remuneration levels must cater for the needs of employees and procurement administrators must earn high to avoid back-handers and cutting of corners in public procurement which is the case in Sweden. Procurement professionals in turn must be rewarded in accordance with the individual’s performance and the strategy of the company. The SPB must introduce non-monetary incentives like residential stands and mortgages for procurement executives as a move towards motivation.

There must be regular contract audit and monitoring of procurement across government projects like in the case of Tanzania to iron out unethical conducts before they get out of hand. Procurement laws must be reviewed in light of current policy frameworks like ZimAsset. In reviewing the procurement regulations, identification of the factors feeding inefficiency and why it is surviving is paramount. In this regard, there must be a complete overhaul due to inefficient processes of pre-tender and post-tender activities in the project management processes. Procurement laws must have direct relationships with public finance management. Contract management and the procurement function must produce procurement plans that feed into the budget to ensure effective review of the efficiency of the procurement processes.

The SPB must be adequately strengthened and funded and relevant tender processes must be used instead of “deals”. Due to the intricate nature of procurement big business and limited operational and fiscal independence, the government must upgrade the SPB by creating an independent ministry and appointing a procurement minister to oversee government contracts.

Lack of keeping to payment and failure to address potential conflicts are outlining risks that commonly arise due to incessant changes within governments in Africa. In the case of inclusive governments, procurement professionals must be ready for potential problems and must avoid signing long-term service agreements unless there is an outstanding advantage and a stable environment which can facilitate effective procurement planning and control.

Another key recommendation is that the whole legal and administrative framework currently governing the public procurement system in Zimbabwe should be reviewed. It would be noble if the Public Procurement system in Zimbabwe is reviewed in view of the current reform proposals championed by the office of the president and cabinet (OPC) under its Modernisation Department. This can be done under the auspices of the new public management concept with a thrust in the reinvention of government model.

The above envisaged recommendation of reforming the Public procurement system should ensure that the Procurement Act [Chapter 22:14] is amended or repealed in order to streamline the functions of the Board. Currently, the Board has two-pronged functions: Supervision and policy direction and spearheading actual transactional procurement. This flies in the face of best practice, corporate governance principles and has a tendency of adulterating the capacity of the Board in the execution of its constitutional mandate. The Board should only be retained for policy direction, monitoring and supervision and transactional procurement should be decentralised to procuring entities in government Ministries, parastatals, public enterprises and other quasi-governmental agencies.

This means that the Accounting Officers of these different government and government agencies will be the heads of such procurement entities and should be accountable to the Board for policy direction, monitoring and evaluation and supervision. Therefore, the checks and balances mechanism between the accounting officers of the procurement entities and the board will go a long way to mitigate graft and all forms of corruption and irregularities that have been allegedly associated with the Zimbabwean procurement system. However, this reform crusade should be coupled with a strong capacity building framework and financial mechanism as a strategy of implementing the recommendations proposed in this installment.

References

- Tanzi V (1998) Corruption Around the World: Causes Consequences Scope and Cures. International Monetary Fund Working Paper Fiscal Affairs Department

- Zhou G (2000) Public Enterprise Sector Reforms in Zimbabwe: A Macro Analytical Approach Abstract Zambezia.

- Moyo JN (2011) “What are the challenges of Public Administration today in Zimbabwe”. University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe.

- Kunaka C, Matsheza P (2002) The SADC Protocol Against Corruption: A Regional Framework to Combat Corruption. Human Rights Trust of Southern Africa (SAHRITT), Harare.

- Thebald R (1990) Corruption Development and Underdevelopment. Durke University Press, Durham.

- Moyo JN (1992) The Politics of Administration: Understanding Bureaucracy in Africa. SAPES Books, Harare.

- Derbyshire JD (1984) An Introduction to Public Administration: People Politics and Power. McGraw-Hill, London.

- Machokoto S (2000) “A critical assessment of ethics and accountability (Professionalism) within public organisations: The case study of Harare Department of housing community services (DHS)”. University of Zimbabwe, Harare.

- Mupanduki MM (2012) An Analysis of the Nature of and Remedies for Corruption in Sub-Sahara Africa: Focusing on Zimbabwe. UMI Dissertation Publishing, New Jersey.

- Andvig JC, Fjeldstad OH (2000) Research on Corruption: A Policy Oriented Survey. Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo.

- Maslow AH (1970) Motivation and Personality. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- Weber M (2002) Bureaucracy. Roxbury Publishing Company, Perkin.

- Tambulasi RIC (2010) Reforming the Malawian Public Sector: Retrospective and Prospectives. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), Dakar.

- Government moves to step up indigenisation (2014) The Standard 19-25 January 19.

- Mugabe must lead corruption fight (2014) The Standard 9-15 February 9.

- Procurement Act [Chapter 22:14] (Acts 2/1999 22/2001)

- Corruption Perceptions Index 2009 to 2013.

- Matsheza P and Kunaka C (2000) Ant-Corruption Mechanism and Strategies in Southern Africa. Human Rights Research and Documentation Trust of Southern Africa (HRDTSA), Harare.

- Amundsen I, Andrade VP (2009) Public Sector Ethics. Catholic University of Angola, Luanda.

- Andrews Y (2001) The Personnel Function Pretoria. Haum

- Arrowsmith S, Treumer S, Fejo J, Jiang L (2011) Public Procurement Regulation: An Introduction University of Nottingham, EUROPEAID Co-operation Office

- Odhiambo W, Kamau P (2003) Public Procurement: Lessons from Kenya Tanzania and Uganda. Institute of Development Studies, Nairobi.

- Musanzikwa M (2013) Public Procurement System Challenges in Developing Countries: the Case of Zimbabwe. International Journal of Economics Finance and Management Sciences 1: 119-127.

- Bovis CH (2007) European Union Public Procurement Law. Elgar European Law Series, Edward Elgar Publishing

- Mamiro RG (2004) Value for Money The Limping pillar in Public Procurement- Experience from Tanzania. Institute of Accountancy, Arusha.

- Kennedy SS, Malatesta D (2010) Safeguarding the Public Trust: Can Administrative Ethics Be Taught?. Journal of Public Affairs Education 16

- Holtzhausen N (2007) Whistleblowing and Whistleblower Protection in the South African Public Sector. University of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Zhou G (2012) Three Decades of Public Enterprise Restructuring in Zimbabwe a will-Of-The-Wisp Chase?. Harare International Journal of Humanities and Social Science

- Huntington SP (1968) Political Order in Changing Societies. Yale University Press, USA.

- Chitiyo K (2009) The case for Security Sector Reform in Zimbabwe. Royal United Services Institute, Occasional Paper, Printed Stephen Austin and Sons

- Hyden G, Venter D (2001) Constitution-making and Democratization in Africa. Africa institute of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Chizu N (2013) Framework in Public Procurement Critical The Newsday 28 October 12.

- Chizu N (2013) Fundamentals of Procurement in Developing CountriesThe Newsday 28 October 9

- Teorell J (2007) Corruption as an Instituton: Rethinking the Nature and Origins of the Grabbing Hand. QoG Working Paper Series

- Buchanan J, Tollison D (1984) The theory of public choice II. University of Michigan, The University of Michigan press

- Buchanan JM (2003) Public Choice: Politics without Romance Policy Centre for Independent Studies.

- Procurement Regulations [Chapter 22:14] (Statutory Instrument 171 of 2002)

- The new Constitution of Zimbabwe 2013 [Chapter 17 Part 6] 315

- Mushava E (2014) Zinara Boss in $2 million tender scam The Newsday 10 February 2.

- Musarurwa D and Chitemba B (2014) Government cancels ZESA tender The Sunday Mail 26 January - 1 February

- Zengeni H (2014) ZETDC tender raises eyebrows: State Procurement Board rules violated; US$35m facility in question The Herald 7 February

- Zengeni H (2014) Companies to procure 50 percent of goods locally The Herald 7 February

- Leach A (2013) The CIPS Pan-Africa Conference highlighted how in the face of the continuing challenges buyers must take responsibility for change The International Magazine for Supply Chain Professionals 18: 43

- Langa V (2012) REA equipment lies idle The Newsday 2 February 3

- Matimire K (2013) REA lights up 10 per cent of rural areas The Zimbabwean 12 December 15

- Chitemba B (2014) Shock as Airport Road gobbles up US$80 million The Sunday Mail 23-29 March

- General Laws Amendment Bill (2010) BPRA’s position on centralization of tender processes and procurement Bulawayo Progressive Residents Association (BPRA)

- Zhou G and Zvoushe H (2012) Public Policy Making in Zimbabwe: A Three Decade Perspective International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2

- Giugale M (2013) ZimAsset dead with corruption The Newsday 25 November 8

Copyright: © 2016 Magaya K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.