Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

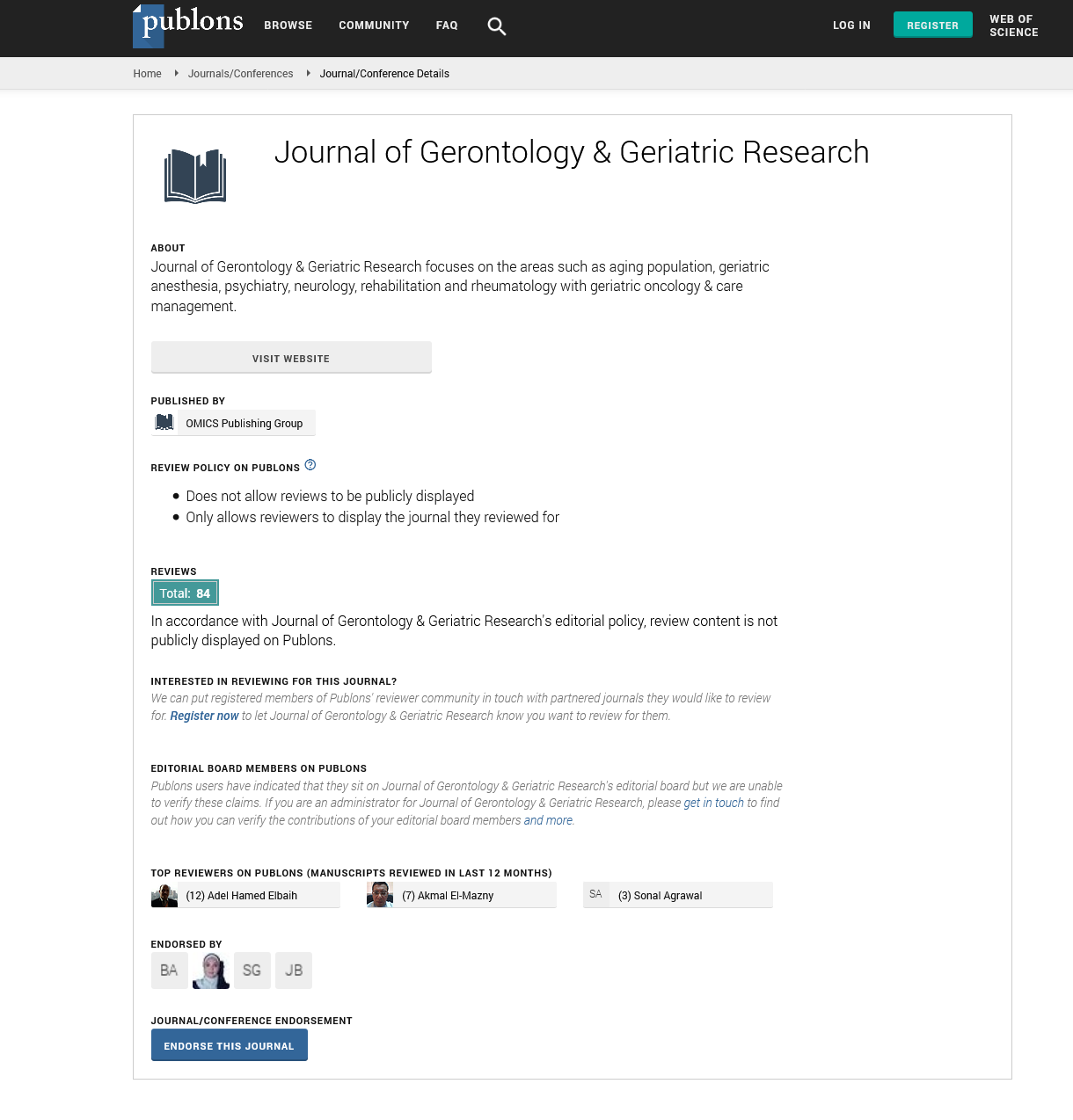

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Editorial - (2022) Volume 11, Issue 5

A Note on Predictors of Health in Older Adults

Alison Chasteen*Received: 02-May-2022, Manuscript No. jggr-22-17196; Editor assigned: 04-May-2022, Pre QC No. P-17196; Reviewed: 12-May-2022, QC No. Q-17196; Revised: 18-May-2022, Manuscript No. R-17196; Published: 23-May-2022, DOI: 10.35248/2167-7182.2022.11.615

Editorial

A composite indication of self-assessed health, functional capacities, and life meaning is used to determine healthy ageing. The impact of the healthy lifestyle index, psychosocial index, and socioeconomic position on the likelihood of healthy ageing is assessed using logistic regression models (i.e. being healthy at older age). The lifestyle and psychosocial indexes are made up of a variety of behaviours that are thought to be beneficial for ageing well. Models are examined for three age categories of older people: 60– 67, 68–79, and 80+, as well as three countries: Western, Southern, and Central-Eastern Europe. In terms of external variables, socioeconomic position has been identified as the most important influencing factor in promoting the highest levels of health fragility. In reality, cardiovascular disease and mortality were found to differ between high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries, with the poorest countries facing higher risks. Nonetheless, socioeconomic status is a multifaceted concept that is linked to both money resources and educational attainment. The latter was discovered to be the most consistent indicator of socioeconomic status (rather than wealth), with people with low education levels in low- and middle-income countries having a significantly higher risk of major cardiovascular events, for example, than those with higher education levels [1].

In recent decades, the world's population has become older. According to World Bank data (2020), 9.321 present of the entire global population is 65 years or older, up 3.069 present since 1990. According to global forecasts, life expectancy will rise by two-thirds in low- and middle-income nations by 2050, when two-thirds of the population would be over 60. Furthermore, the present pandemic has underlined the necessity to explore issues in policies and activities in order to maintain well-being, quality of life, and active ageing in the face of demographic transition. By declaring 'The Decade of Healthy Ageing,' the World Health Organization (WHO) is leading an international commitment to improve the lives of older people, their families, and communities, stating: 'A decade of concerted global action on healthy ageing is urgently needed to ensure that older people can fulfil their potential in dignity and equality, in a healthy environment.' Four themes are at the heart of the action areas: ‘Age-friendly environments' and better places to promote non-discriminatory opportunities free of physical and social barriers; 'Combating Ageism,' an effort to reduce and eliminate negative behaviours, perceptions, prejudices, and stigma that have negative effects on the well-being and health of older people; 'Integrated care,' with non-discriminatory access to health services; and 'Long-term care,' with non-discriminatory access to health services Given that a healthy old age is linked to well-being during the ageing process, sociogerontological studies have found that certain daily activities (such as leisure and voluntary activities, among others), as well as a positive attitude toward life itself, have a positive impact on quality of life. Furthermore, classic authors (for example, Havighurst, Spreitzer and Snyder, and Brandtst, among others) defend the idea that activity is critical to achieving a higher quality of life as we age [2].

Rowe and Khan's traditional definition of ageing in good health, which refers to the notion of successful ageing, is based on the balance of three components: absence of disease and disease-related impairment, high functional capability, and active participation in life. It had a big influence on a lot of following definitions. Initially, the majority of them were based on a biomedical approach to healthy ageing that used objective, often clinical, markers, but later on, subjective measures of health status, such as self-rated health, were added to the mix. The lifestyle index, which includes vigorous and moderate physical activity, consumption of vegetables and fruits, regular meal eating, and appropriate liquid consumption, is linked to healthy ageing, with each of the elements in the index increasing the likelihood of being healthy at an older age. Individuals who age healthily have a much higher index score (on average by 1 point for men and 1.1 point for women). The psychosocial index, which includes work, outdoor social participation, indoor activities, and life satisfaction, has also been found to be highly associated to health, with each point of the index score increasing the likelihood of healthy ageing. In the population under the age of 68, there is an educational gradient in healthy ageing [3].

The presented definitions became increasingly precise in assessing the criteria that must be met to define healthy ageing, such as the absence of any significant or specific illness, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or a previous cancer diagnosis; no limitations in performing basic Activities of Daily Living (ADL); freedom from clinically significant cognitive impairments and depression symptoms; high cognitive and physical functions, and active lifestyles. Specific clinical assessment markers were frequently used to support these assessments. The psychosocial viewpoint on healthy ageing includes multidimensional models that depict the process of adjusting to an older stage of life using objective and subjective markers as well as lay people's conceptions of healthy ageing. The concept of "doing and having" as well as "going and doing" is included in psychosocial models of healthy ageing, as are experiences associated to the continuance of significant former social activities (having paid work, volunteer work, domestic tasks, active participation in community, social support from family, friendship, economic security, sport, travel and creative activities) [4,5].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Beard JR. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016;387:2145-2154.

- Carta MG. Association of chronic hepatitis C with major depressive disorders: irrespective of interferon-alpha therapy. Cli Prac Epidem Mental Health. 2007;3:1-4.

- Dorr DA. Use of health‐related, quality‐of‐life metrics to predict mortality and hospitalizations in community‐dwelling seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:667-673.

- Gallegos-Orozco J. Health-related quality of life and depression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:124-129.

- Golden J. Depression and anxiety in patients with hepatitis C: Prevalence, detection rates and risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:431-438.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Citation: Chasteen A (2022) A Note on Predictors of Health in Older Adults. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 11:615.

Copyright: © 2022 Chasteen A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.