Indexed In

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2021) Volume 5, Issue 2

Vasoplegic Shock after Pheochromocytoma Resection: The Role of Methylene Blue

Ramos Matias*, Fratebianchi Franco and Verlangieri StellaReceived: 16-Feb-2021 Published: 10-Mar-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2684-1606.21.5.141

Abstract

We present a case of a patient with hypotension refractory to the administration of norepinephrine after laparoscopic pheochromocytoma resection in the left adrenal gland. We describe the use of methylene blue as an alternative drug therapy to the adrenergic system, as well as associated doses, contraindications and complications.

Keywords

Pheochromocytoma; Vasoplegic shock; Catecholamines; Methylene blue

Abbrevations

MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; NOS: Nitric Oxide Synthase; NO: Nitric Oxide; GC: Guanylate Cyclase; GMP: Guanosine Monophosphate; GTP: Guanosine Triphosphate

Introduction

The perioperative management of pheochromocytoma is a challenge for the perioperative medical team. From preoperative optimization to management of adrenergic crises in the operating room, the role of the anesthesiologist is crucial in order to obtain good results. In particular, hypotension after surgical isolation of the tumor can be a problem given its refractoriness to commonly used vasoactive agents. We will describe the use of methylene blue in a case of vasoplegic shock refractory to norepinephrine.

A 56-year-old, male ASA-III patient presented with an adrenal tumor identified as pheochromocytoma, scheduled for laparoscopic adrenalectomy. At the pre-anesthetic visit, he revealed a history of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, myocardial infarction that required placement of a metal stent in the right coronary artery, and type I neurofibromatosis. His usual medications included: Valsartan, ivabradine, metformin, digoxin, rosuvastatin, clopidogrel, nebivolol, levothyroxine, acetylsalicylic acid, doxazosin, and acenocoumarol. Acenocoumarol and clopidogrel were suspended five days before surgery, according to current recommendations [1]. Preoperative studies included an echocardiogram that reveals global hypokinesia, eccentric ventricular hypertrophy, ejection fraction of 38%, decreased right ventricular function (14 mm TAPSE), and mild mitral regurgitation. Coronary angiography shows the anterior descending artery free of lesions, the circumflex artery with a severe lesion that compromises its lumen by 70% and the right coronary artery with severe stent restenosis that decreases its lumen by 95%.

On the day of surgery, the blood pressure on admission to the operating room was 132/76 mmHg and the heart rate was 86 beats per minute (bpm). He was premedicated intravenously with midazolam (2 mg) and fentanyl (75 ug), basic monitors were placed and the radial artery was catheterized. After induction with fentanyl (6 mcg/kg), propofol (1 mg/kg) and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg), an ultrasound-guided central venous catheter was placed in the right internal jugular. Remifentanil (0.4 mcg/kg/min) and sevoflurane (% et sevoflurane 1.4) were used for maintenance of anesthesia.

During surgery, Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) was maintained between 70 and 90 mmHg with an infusion of norepinephrine (initial dose 0.033 ug/kg/min). Due to surgical manipulation, the tumor released catecholamines causing hypertensive crises that required the administration of sodium nitroprusside in infusion titrated between 1 to 2.5 ug/kg/min plus boluses of phentolamine of 2 mg. There was an episode of sinus tachycardia of 145 bpm associated with 270/130 mmHg of blood pressure that required the administration of 0.5 mg/kg of esmolol.

Minutes after clamping of the effluent vein, a hypotensive crisis precipitated. All vasodilators were suspended and the norepinephrine infusion was restarted at 0.15 ug/kg/min, which, given the lack of response, was titrated to a dose of 0.7 mcg/kg/ min. MAP continued at 40 mmHg despite fluid therapy with lactated Ringer and there was no response to boluses of 50 ug of norepinephrine.

Although the adrenergic discharges produced by the release of catecholamines by the tumor configure a cardiac challenge, which in the context of an organ damaged by ischemic heart disease could be a trigger for cardiogenic collapse, hypotension, tachycardia and low central venous pressure (4 mmHg) was interpreted as vasoplegic shock. In favor of this interpretation is the surgical context and the temporal correlation with the vascular isolation of the tumor, the absence of electrocardiographic signs of cardiac ischemia, and the absence of pulmonary changes suggestive of acute lung edema.

Given the lack of vasopressin in our institution and given the evident inefficiency of adrenergic agonists for the control of blood pressure, it was decided to administer methylene blue, 10 mg bolus and then 60 mg more as an infusion over 10 minutes. Once the administration was finished, blood pressure began to gradually recover during surgical closure and it was necessary to decrease the dose of norepinephrine. After the surgery, the patient was extubated in the operating room and the vasoactive drugs were suspended. He was transferred to the coronary unit lucid and hemodynamically stable. His vital signs upon admission were: Heart rate 107 bpm, blood pressure 120/70 (89) mmHg, SpO2 95% in ambient air and 18 breaths per minute. The patient was discharged from the closed unit three days later.

Results and Discussion

This case shows the effect of an abrupt cut in the supply of endogenous catecholamines by the pheochromocytoma after its surgical isolation. The sudden decrease in the concentration of catecholamines, the decrease in adrenergic receptors on the cell surface, and the residual action of adrenergic antagonists caused a hypotensive crisis that required the rapid intervention of the medical team. Most of the time, the body responds to the suspension of vasodilators, adequate fluid therapy, and the infusion of exogenous catecholamines. In this case, aggressive use of adrenergic drug therapy with norepinephrine was completely ineffective, leading to the diagnosis of catecholaminerefractory vasoplegic shock [2]. Pharmacological alternatives were immediately considered, and vasopressin was a great candidate [3], due to its lack of availability in our institution, it was ruled out.

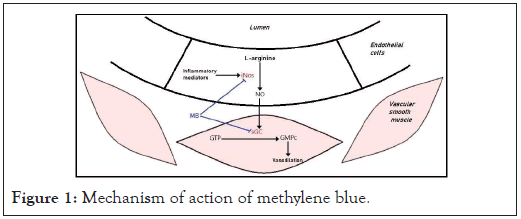

We know that surgical stress and inflammatory phenomena promote the activation of the inducible isoform of Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) in the vascular endothelium. This enzyme, of which there are three isoforms (nNOS, eNOS and iNOS), catalyzes the reaction that produces Nitric Oxide (NO) from L-arginine. The produced NO diffuses into the muscle layer which is part of the wall of the microcirculation and there activates the enzyme Guanylate Cyclase (GC) [4]. GC catalyzes the reaction by which cyclic Guanosine Triphosphate (GTP) forms cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP). This latter mediator participates as a second messenger, activating kinases and finally promoting the decrease in intracellular calcium concentration. Calcium plays a fundamental role as a trigger for smooth muscle contraction, so its decrease leads to the reverse phenomenon: Smooth muscle relaxation. This, in the vascular tree, translates as vasodilation and the consequent loss of peripheral vascular resistance (Figure 1). The end result is a drop in afterload, which, even with normal or even increased cardiac output, the body loses the ability to generate adequate blood pressure for perfusion.

Figure 1: Mechanism of action of methylene blue.

Methylene blue does not depend on the availability of adrenergic receptors for the recovery of muscle tone since it crosses cell membranes and acts by inhibiting iNOS and GC in vascular smooth muscle [5]. This dye, outside of the perioperative context, has been used for the treatment of methemoglobinemia, priapism and malaria, showing an adequate safety profile for its use. In the field of critical care and anesthesia, methylene blue has proven to be useful in vasoplegia in cardiac surgery [6], in reperfusion of liver transplantation, in anaphylactic shock and in burn patients [7].

The dose of methylene blue usually used according to research on septic shock, cardiac surgery or anaphylaxis is 1 to 2 mg/kg [8]. Toxic manifestations have been reported with doses of 7 mg/kg. After ruling out contraindications, such as the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors or glucose 6 phosphatase deficiency, it was decided to administer 1 mg/kg of methylene blue. This produced a substantial improvement in the hemodynamic profile, which manifested in the need to decrease the dose of norepinephrine as blood pressure recovered to normal values. The result was similar to that obtained in a previous report, but in a pediatric case [9].

Methylene blue, like deoxyhemoglobin, absorbs the 660 nm wavelength light emitted by the saturometer. This can be interpreted by the device as arterial desaturation [10]. In our case, this phenomenon was no observed.

Conclusion

This case report shows the hemodynamic response to methylene blue of a catecholamine-refractory vasoplegic shock secondary to pheochromocytoma resection. We believe that the improvement was not just a coincidental correlation, but higher quality research should be done to provide better evidence. We are sure that the anesthesiologist must have a low threshold to start therapy with pharmacological alternatives to the adrenergic system in order to achieve hemodynamic stability once hypovolemia is corrected. However, scientific evidence supporting the use of methylene blue is not of high quality, we believe that this agent should not be used as a first treatment option. We hope that the report of this case, with others, will be the basis for the development of trials of greater complexity and scientific quality in the future in order to obtain better clinical evidence.

Consent

The authors declare that the informed consent of the patient has been obtained for the publication of this work.

REFERENCES

- Kozek-Langenecker S, Ahmed A, Afshari A, Albaladejo P, Aldecoa C, Barauskas G, et al. Management of severe perioperative bleeding. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017; 34(6): 332-395.

- Landry DW, Oliver JA. The pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345: 588-595.

- Augoustides J, Abrams M, Berkowitz D. Vasopressin for hemodynamic rescue in catecholamine-resistant vasoplegic shock after resection of massive pheochromocytoma. Anesthesiology. 2004; 101: 1022-1024.

- Mayer B, Brunner F, Schmidt K. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis by methylene blue. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993; 45: 367-374.

- Faber P, Ronald A, Millar BW. Methylthioninium chloride: Pharmacology and clinical applications with special emphasis on nitric oxide mediated vasodilatory shock during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60: 575-587.

- Leyh RG, Kofidis T, Strüber M, Fischer S, Knobloch K, Wachsmann B, et al. Methylene blue: The drug of choice for catecholamine-refractory vasoplegia after cardiopulmonary bypass? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 125: 1426-1431.

- Hos-seinian L, Weiner M, Levin MA, Fischer G W. Methylene Blue. Anesth Analg. 2016; 122(1): 194-201.

- McCartney SL, Duce L, Ghadimi K. Intraoperative vasoplegia: Methylene blue to the rescue! Curr Op in Anaesthesiol. 2018; 31(1): 43-49.

- Amin Nasr A, Fatani J, Kashkari I, Al Shammary M, Amin T. Use of methylene blue in pheochromocytoma resection: Case report. Pediatr Anesth. 2009; 19(4): 396-401.

- Kessler MR. Spurious pulse oximeter desaturation with methylene blue injection. Anesthesiology. 1996; 65: 435-436.

Citation: Matias R, Franco F, Stella V (2021) Vasoplegic Shock after Pheochromocytoma Resection: The Role of Methylene Blue. J Surg Anesth. 5:141.

Copyright: © 2021 Matias R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.