Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

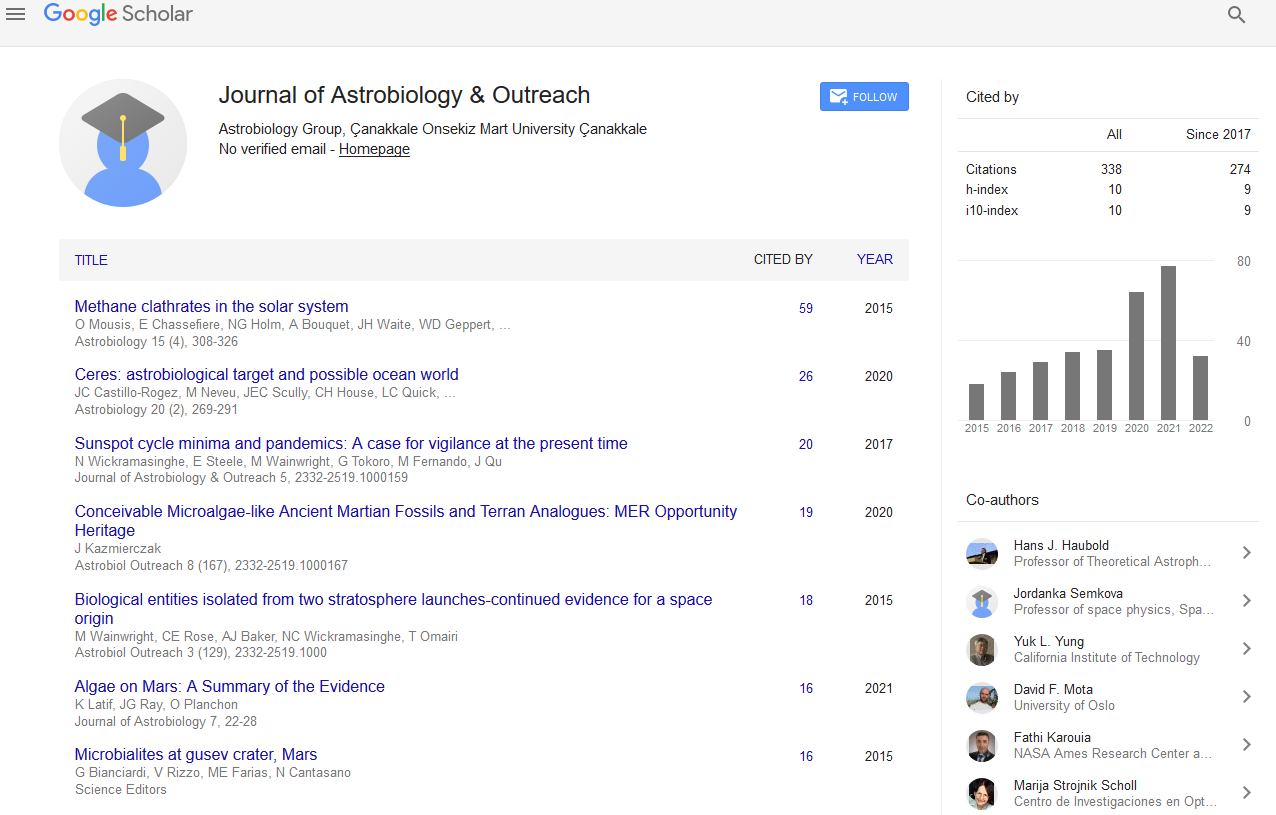

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Commentary - (2025) Volume 13, Issue 4

The Origin of Life Bridging Chemistry Biology and Astrobiology

Adam Hibberd*Received: 28-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. JAO-25-29921; Editor assigned: 01-Dec-2025, Pre QC No. JAO-25-29921 (PQ); Reviewed: 15-Dec-2025, QC No. JAO-25-29921; Revised: 22-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JAO-25-29921 (R); Published: 29-Dec-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2332-2519.25.13.390

Description

The question of how life began on Earth remains one of the most profound and fascinating inquiries in science. The origin of life, or abiogenesis, refers to the process by which simple, nonliving chemical compounds gave rise to self-replicating systems that eventually evolved into complex organisms. While definitive answers remain elusive, significant advances in astrobiology, chemistry and molecular biology have provided important clues about the conditions that may have enabled the transition from chemistry to biology.

Early Earth, around 4.5 to 3.5 billion years ago, was a dynamic environment characterized by volcanic activity, hydrothermal systems and a reducing atmosphere. The presence of water, carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia and other compounds set the stage for prebiotic chemistry. According to the “primordial soup” hypothesis, these ingredients accumulated in oceans and ponds, where energy sources such as lightning, ultraviolet radiation and geothermal heat drove chemical reactions. This idea gained experimental support from the Miller-Urey experiment in 1953, which demonstrated that amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, could form spontaneously under simulated early Earth conditions.

Another influential perspective emphasizes the role of hydrothermal vents at the ocean floor. These environments provide both chemical gradients and catalytic mineral surfaces, which could facilitate the synthesis of organic molecules. Alkaline hydrothermal vents, in particular, generate natural proton gradients across mineral membranes, resembling the chemo osmotic principles that sustain modern cellular metabolism. This has led to the suggestion that life may have originated in these submarine environments, where simple molecules assembled into more complex polymers.

Central to the origin of life is the question of heredity. Modern biology relies on DNA and proteins, but both are highly complex. To resolve this paradox, researchers proposed the “RNA World” hypothesis, suggesting that RNA could have acted both as a genetic material and as a catalyst. Indeed, ribozymes RNA molecules with enzymatic functions support the plausibility of a pre-DNA world where RNA played dual roles. Over time, DNA and proteins may have taken over specialized tasks, giving rise to the central dogma of biology.

Another possibility is that life emerged from self-organizing systems, where lipids and amphiphilic molecules formed primitive membranes, enclosing metabolic reactions and genetic material. Protocells, simple compartments with selective boundaries, would have provided the structural basis for evolution by natural selection. Once self-replicating molecules were contained within protective vesicles, the process of Darwinian evolution could begin, gradually increasing complexity and stability.

Astrobiology expands the discussion beyond Earth, exploring whether similar processes might occur elsewhere in the universe. The discovery of organic molecules in meteorites, such as the Murchison meteorite and the detection of complex compounds on comets and interstellar dust suggest that the basic ingredients of life are widespread. Extraterrestrial environments like the subsurface oceans of Europa and Enceladus, or the methane-rich atmosphere of Titan, provide natural laboratories to test theories of prebiotic chemistry. If life originated more than once in the cosmos, it would imply that the transition from chemistry to biology is a common outcome under suitable conditions.

Conclusion

Despite decades of research, the origin of life remains unsolved, but this mystery drives interdisciplinary exploration. Advances in synthetic biology and laboratory simulations are bringing scientists closer to constructing life-like systems from non-living materials, helping to illuminate plausible pathways from molecules to cells. Whether life began in a warm pond, a hydrothermal vent, or was seeded from space through panspermia, the question touches on both scientific curiosity and philosophical wonder.

Citation: Hibberd A (2025). The Origin of Life Bridging Chemistry Biology and Astrobiology. J Astrobiol Outreach.13:390.

Copyright: © 2025 Hibberd A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited