Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

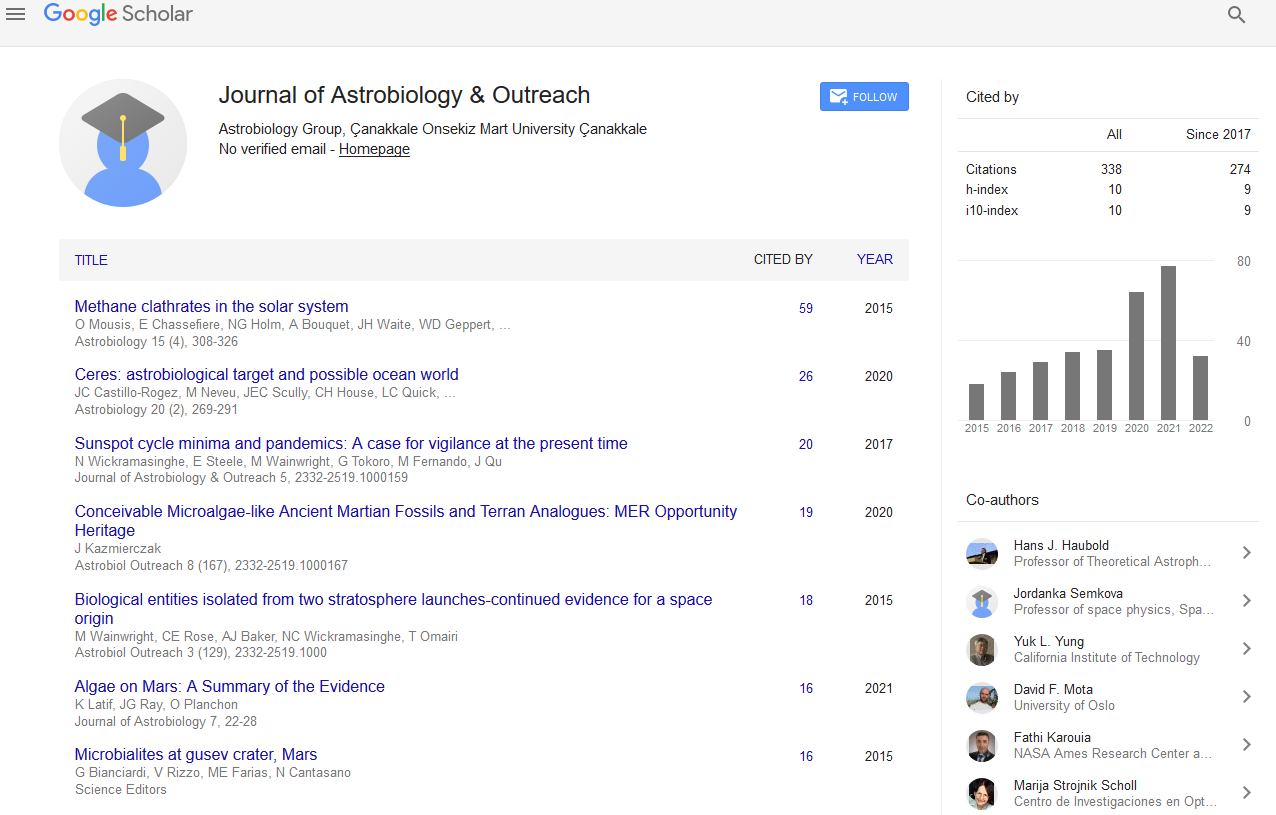

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Perspective - (2025) Volume 13, Issue 3

The Chemistry That Made Life and Its Lessons for the Universe

James Brady*Received: 29-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. JAO-25-30648; Editor assigned: 01-Sep-2025, Pre QC No. JAO-25-30648 (PQ); Reviewed: 15-Sep-2025, QC No. JAO-25-30648; Revised: 22-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. JAO-25-30648 (R); Published: 29-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2332-2519.25.13.384

Abstract

Description

The question of how life began on earth is one of science’s greatest mysteries. Central to this inquiry is prebiotic chemistry the study of the chemical reactions that preceded the formation of the first living systems. By investigating how simple molecules self-assembled into complex structures capable of supporting life, scientists are not only uncovering the origins of life on our planet but also gaining insight into the potential for life elsewhere in the universe. The chemistry that made life on earth provides a roadmap for understanding the conditions necessary for life, the universality of biochemical pathways, and the signals we might detect on other worlds.

Life as we know it is built from a relatively small set of molecules, including amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and sugars. Prebiotic chemistry seeks to explain how these essential building blocks could arise naturally under early Earth conditions. Experiments have shown that simple molecules such as water, carbon dioxide, methane, and ammonia can, under the right conditions, combine to form amino acids and nucleotides the precursors to proteins and nucleic acids. Classic experiments, such as the Miller-Urey experiment, demonstrated that electrical sparks in a mixture of early -earth gases could produce amino acids, offering the first laboratory evidence that the raw materials of life can form spontaneously. Modern research has expanded these findings to include other energy sources, such as ultraviolet light, hydrothermal activity, and mineral catalysis, revealing multiple pathways through which prebiotic molecules can emerge.

Beyond forming building blocks, prebiotic chemistry investigates how these molecules organize into systems capable of replication and metabolism. One prominent theory, known as the RNA world hypothesis, posits that RNA molecules capable of both storing genetic information and catalyzing chemical reactions played a central role in early life. Laboratory studies have shown that RNA nucleotides can polymerize under plausible prebiotic conditions, and that RNA strands can evolve catalytic functions. Other models suggest that metabolic networks could have arisen on mineral surfaces or in hydrothermal vent systems, where chemical gradients provide energy for self-sustaining reactions. These investigations highlight that life may not have arisen from a single reaction but rather from a network of chemical processes acting in concert.

Prebiotic chemistry also informs the search for life beyond earth. By understanding the chemical pathways that led to life on our planet, scientists can identify other environments in which similar processes might occur. Mars, for example, has evidence of past liquid water, volcanic activity, and organic molecules, making it a prime candidate for studying prebiotic chemistry. Similarly, icy moons like Europa and Enceladus harbor subsurface oceans and geothermal energy, conditions that could support chemical reactions analogous to early earth. Even distant exoplanets with the right combination of water, carbon, and energy sources may be capable of forming prebiotic molecules, broadening the scope of habitable environments in the galaxy.

The study of prebiotic chemistry also emphasizes the universality and resilience of life’s chemical foundations. Extremophiles on earth microorganisms that thrive in high heat, acidity, salinity, or radiation demonstrate that life can adapt to environments once considered inhospitable. Their existence suggests that if the right chemical ingredients are available, life may emerge and persist under a variety of planetary conditions. This perspective shifts the search for life from simply finding earth-like planets to identifying worlds where essential chemical pathways could occur.

In conclusion, chemistry that made life on Earth provides both a blueprint and a lesson for understanding the universe. By studying the formation, organization, and evolution of prebiotic molecules, scientists can identify potential habitats for life, interpret biosignatures on other worlds, and appreciate the remarkable resilience of living systems. In essence, prebiotic chemistry offers a bridge between Earth’s earliest history and the broader search for life, revealing that the processes that created life here may not be confined to our planet but could be at work across the cosmos.

Citation: Brady J (2025) The Chemistry That Made Life and Its Lessons for the Universe. J Astrobiol Outreach.13:384.

Copyright: © 2025 Brady J. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.