Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- SWB online catalog

- Publons

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2023) Volume 11, Issue 1

Philosophical and Public Administration in China and Western Countries

Olga Gil*Received: 02-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. IPR-23-19519; Editor assigned: 05-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. IPR-23-19519 (PQ); Reviewed: 19-Jan-2023, QC No. IPR-23-19519; Revised: 26-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. IPR-23-19519 (R); Published: 03-Feb-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2375-4516.23.11.216

Abstract

This work shows differences in public participation in China and Western countries, conceptually and empirically. To do so, the different philosophical and public administration traditions are outlined. Main contributions are tables and dashboards to allow general comparisons and to differentiate contexts in both political settings, besides being useful for other settings.

The tables included are:

• Deliberative democracy,

• The Gil Dashboard of endogenous foundations for change both in China and the West

Keywords

Democracy; Public participation; European Union; Administration

Introduction

According to Anthony Kenny, Philosophy is not a matter of knowledge; it is a matter of understanding, of organizing what is known. Kenny maintains that once problems can be unproblematically stated, when concepts are uncontroversially standardized then we have a science setting up home independently, rather than a branch of philosophy. In this work, a subfield of political science that has been established independently will be reviewed and questioned: Public participation within public administration [1]. We are going to analyse public participation in the light of political philosophy, or “how we live together”, as stated by Ongaro [2]. And it will be defended that there are questions related to philosophy that have not been completely settled in the subfield of public administration. These questions are more evident when we compare public administration in the east and the western traditions. Therefore, political theory should be placed at the center of our inquiries. These questions related to philosophy that have not been completely settled are more evident when we compare public administration in the East and the Western traditions. Thus, a fundamental question of this philosophical inquiry will be from the perspective of political theory: do the philosophical foundations of public participation are different from the west in the Chinese context? Our tentative hypothesis is that yes indeed, the foundations of public participation are different from the West in the Chinese context. Moreover, these differences, in practice, are broader than theoretical models of public administration would suggest. In so doing, political philosophy throws light to understand these differences, in particular, when we study typologies of democratic innovations.

This work will be done with an eye in a case of innovation. Innovation is a crucial theme for public administration all over the world. It is more so today in the context of economic crisis, recurrent budget constraints and the challenges facing governments associated with the Millennium Development Goals. These goals need efforts to promote economic growth and address social needs such as education, health, social protection, and job opportunities, while tackling climate change and environmental protection globally [3]. The work is also concerned with the fact that since 2015 the world has changed dramatically, with life becoming more difficult and challenging for the west, yet across Asia these are hopeful times, with rising wealth opening its scale. Isolation and fragmentation in the west stands in sharp contrast with what has happened in the Silk Roads since 2015 with first, the shift of global GDP from the developed economies to the east and China emphasis on the mutual benefits of a platform for long term cooperation and collaboration. As president Xi said in Astana in 2013, peoples of the Silk Roads are of “different races, beliefs and cultural backgrounds (and) fully capable of sharing peace and development.” The Silk Roads initiative has surged from the original 63 to 130 countries in 2019. Within these world challenges, what is the importance of context as a force shaping and constraining policies-and more broadly public administration in China as compared to Western societies? For the purpose of this work context will be analysed within the field of public participation in innovative policy design, with an eye on typologies of democratic innovations. Pollitt considers context as the missing link, and a necessity to understand PA innovation. Thus, context could be an administrative paradigm, administrative culture, administrative tradition, a political administrative regime, or reform trajectories that may help as an explanatory framework. In this work, philosophical foundations of the political-administrative regimes will be examined as context in the case of study. Reasons for the study lie in the fact that public organizations around the world are facing unprecedented challenges to their legitimacy [4].

Context and innovation

This work analyses context theoretically in China as compared with western countries, from the philosophical foundations of public participation. Beside trying to show how a particular context works, it shows the ways in which context helps to anchor the status quo and to avoid change, while favouring new policy outcomes. In doing so, it shows the nuances of context and change within the Chinese case as suggested by Ongaro and van Thiel, Ongaro, Pollitt and Bouckaert [3,5]. The work reviews changes related to public participation in smart city plans in the city of Shanghai, and how changes are entangled more broadly to the Confucian contexts and the philosophical foundations of PA in China. Innovation is understood as a form of deliberate, or at least managed; socially purposeful change aimed at attaining something that otherwise would not be achieved, by leveraging on the possibility to do new and different things, to do the same things in different ways, or to enable a different meaning to be given to something. This definition includes innovation in three domains: the first, as product innovation, such as delivering new public services or initiating new policies. The second domain, referred to as process innovation. The third domain: innovation of meaning to accompany societal changes. Based on this framework, innovation is conceptualised in a fourfold way as follows:

1. Innovation as public sector/administrative/public management reform at the level of the public sector in its entirety or large portions of it, and of government wide processes and routines for example, public personnel policies, or the diffusion of performance management systems in the public sector;

2. Innovation at the micro-level, by which we mean something akin to the notion of strategic renewal at the level of individual public organisations and policy networks;

3. Innovation in the economy as enabled by PA; and

4. Innovation in society as enabled or facilitated by PA.

Points (1) and (2) articulate innovation as reform and strategic renewal of the public sector, which exerts an impact on PA and facilitates its development, while points (3) and (4), on the contrary, outline the role of PA as agent or enabler of economic and societal innovation respectively. These domains of innovation will be explored looking at public participation in the first smart city plan in Shanghai. One way to operationalize context is to look at the “how” processes; “top-down/bottom up, legal dimensions and organizational processes.” In this work we will focus on the analysis of how processes from top-down/ bottom up perspectives and the legal dimension. Smart city plans, the case of study we chose includes the three domains of innovation: initiating new policies, innovation of meaning accompanying societal changes and innovation of the economy. When analysing context, we have focused on the how processes, as suggested by Pollitt and Bouckaert [6].

Evolving conceptual frameworks

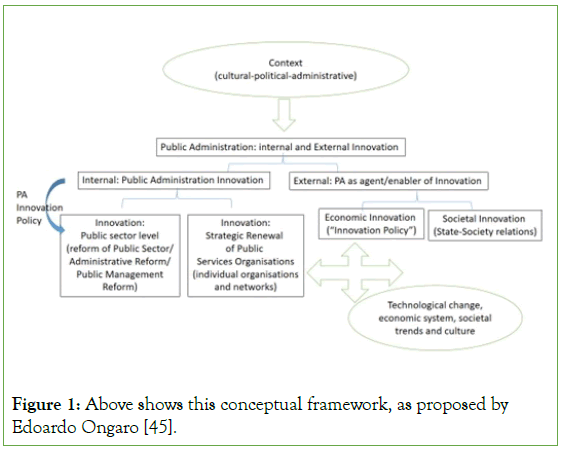

One of the greatest challenges of the public sector is to institutionalize new mechanisms of political participation in order to get support for the practice of governance in its various organizational levels, according to Conteh [7]. This is why political participation is brought to the fore in this work focused on context. This has to do with the fact that there are specific constraints and pressures in the public sector that create a more complex context when compared to private companies’ environments [8]. In order to study innovation in PA in different contexts and in practice, two models or conceptual frameworks are presented and these models are now reviewed. The first model, in Figure 1 sets public administration in the center of the stage, stating that context exerts an influence on innovation. Public administration would also be key to technological change, major changes in the economic system, societal trends and culture. Problems with this model come with the fact that there are no clues on how the process of innovation would occur. We lack the possibility to operationalize context as top-down/bottom up perspective and also in its legal dimension, as proposed by Pollitt and Bouckaert (Figure 1) [6].

Figure 1: Above shows this conceptual framework, as proposed by Edoardo Ongaro [45].

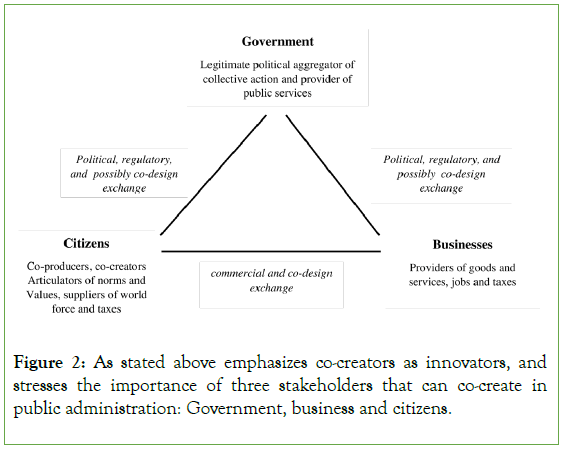

Model two, as Figure 2 shows, proposes a different framework for the analysis of context, whereas government, people and firms could be a salient part of the context for innovation, with the possibilities of co-design open to all actors. But this model has also problems to explain the Chinese context, and its legal dimension.

Figure 2: As stated above emphasizes co-creators as innovators, and stresses the importance of three stakeholders that can co-create in public administration: Government, business and citizens.

Figure 2, emphasizes co-creators as innovators, and stresses the importance of three stakeholders that can co-create in public administration: Government, business and citizens.

Can we think however of a better conceptual framework for the Chinese case, speaking of public administration innovation focusing on the city of Shanghai in China? It will be argued that we need to make endogenous the foundations for change, and we will do it by relating PA and the underlying philosophical foundations of public participation.

A definition of smart cities focusing on human capital

Drawing upon the literature studying smart cities in the last two decades, there are different traditions on the definitions of smart cities. What makes a city smart? For the purpose of this work, since we are focusing on public participation, the focus will be on human capital, and in particular to a definition that opens the smart concept to a wider framework than the artificial intelligence available [9]. Thus, the smart cities definition includes two forms of human intelligence: Human and collective, from the collective skills of population to the social institutions articulating cooperation. Allwinkle and Cruickshank highlight from Hollands’ definitions on human capital the emphasis on people and their interactions [10]. Komninos gives us a nexus to study differences between the philosophical foundations of participation in different contexts when he focuses the definition on the collective skills of population and the social institutions articulating cooperation [9]. The following section reviews public participation in public administration in China and in particular in the first smart city projects in Shanghai. In this part of the research, we have relied on government documents and articles from the press, academic articles, and web pages.

To operationalize the empirical work, for reasons of space the work reflects public administration innovation focusing on a particular case, the city of Shanghai in China–this resource allows introducing new empirical research and methodological details. Thus, the work draws on previous works on the concept of smart city in Shanghai, and focusing on human capital.

Methodology

Hsiao and Yang consider it is possible to map a research area and to broaden knowledge about it with the establishment of a connection pattern between the main publications of the field [11]. This is the method used in this research, where Ongaro´s work on Philosophy and Public Administration has been a point of departure. Other authors have been identified both in the East and the West focusing on philosophical traditions and more recently, on democratic innovations. An approximation of Wittgensteinian ‘families’ of conceptual clusters allows to identify differences determined by context, spaces and processes, further refining the method following Elstub and Escobar [12]. Wittgensteinian ‘families’ of conceptual clusters are to certain extent similar and this allows us to reimagine the role of citizens in governance processes, and to understand renegotiations of the relationship between government and civil society [13]. The analysis is based upon a review of the literature, the results of which are presented in the next section, where we find variations in the use of the terms public participation and democratic innovations. The review was conducted between February and March 2019. Given that this is an emerging field it was decided that a scoping review would be the most effective way of surveying the field. Scoping studies ‘differ from systematic reviews because authors do not typically assess the quality of included studies’ [14]. And they also differ from narrative or literature reviews ‘in that the scoping process requires analytical reinterpretation of the literature’ (Ibid.). We conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed journal articles as well as books and book chapters, based on systematic searches of the databases Web of Science and Scopus and pre-specified inclusion criteria (i.e., key search terms: Philosophica and foundations and public and participation; public and participation and China; no date limit; range of search filters: Title, abstract, topic). The largest combined searches yielded 2.109 results, which were checked for relevance in stages by reading titles, abstracts and conducting in-text searches. The final shortlist of publications that met the criteria was 42 and each paper was coded to locate main concepts, definitions and typologies of democratic innovations. Connection patterns with related and more recent works were established later on through Google Scholar.

The review of the literature helps us first, to establish various basic, non-contingent philosophical principles. Once these are secured, implications are explored taking into account additional and non-philosophical, empirical data and assumptions. Doing so enables us to make some conclusions on the concrete and specific issues of this work; philosophical foundations of public participation in public administration in China. Our choice of case is driven by an interest to learn from innovation practices in different world institutional settings, from using the tools of political philosophy in an applied way, and by an interest to build bridges of understanding in a world where the Silk Roads are a platform relating together different races and cultural backgrounds across the world.

Philosophical foundations of public administration in China

The purpose of this section is to analyze the philosophical foundations of public participation in the East and the differences with the West. In doing so, philosophical issues of justification and legitimacy of public governance are explored in both contexts. The aim is to benefit the field of public administration, as suggested by Ongaro [3]. We focus on the question of what is public participation in the East and the West, and how do they diverge as a philosophical applied inquiry.

Lu and Shi emphasize the importance of guardianship discourse in China, derived from the guardianship model of governance proposed by thinkers like Plato and Confucius [15]. A model “further re-packaged and promoted as an alternate discourse on democracy”, with a primary difference from the liberal democracy discourse in that it promotes paternalistic meritocracy in the name of democracy. Lu and Shi find certain pessimistic views on the average person’s ability to pursue long term and collective interests in the guardianship discourse that emphasizes that the key to quality governance lies in the breeding and selection of morally competent rulers to act as guardians of a society [15]. With their superior knowledge and virtue, the guardians can be trusted to effectively serve the public interest. This discourse requires that the guardians be endowed with the discretionary power and authority that is necessary to make decisions on public issues with limited constraints from the citizenry. Democracy is presented as a government led by competent and virtuous politicians with substantial discretionary power who are willing to listen to people’s opinions, sincere in taking care of people’s interests, and capable of identifying the best policies for their society. Essentially, the guardianship discourse tries to promote paternalistic meritocracy in the name of democracy, following Lu and Shi. Within the guardianship discourse, we have the general doctrine of Confucious that rests on the minben (people-as-the-basis) idea and a virtuous ruler, with ideas of morality upon which society is built and maintained. The leader of the nation shall be an example of moral cultivation, and this example, if followed by society, precludes welfare. The respect for others and their responsible roles in society also help towards cultivating an encompassing sense of virtue. For Confucious, a prerequisite for leadership is the ruler´s sense of virtue, and the so called rules of propriety, including the following:

• If they be led by virtue and uniformity sought to be given by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of shame, and moreover (they) will become good.

• Ministers should serve their prince with faithfulness.

• Importance of the principles of truth and right

• In ordering the people, the importance is to be just.

We could argue that these values expressed by Confucious are references for context. If we want to find context applied nowadays, these values are translated into “the Party’s consciousness of the need to maintain political integrity” which in practice includes an eight-point decision on improving Party and government conduct. The characteristics of the leadership are in tune with Confucious teachings [16]. The legitimacy of the leader rests on responsibility and commitment, as we can see in this presentation of the general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee; “Xi has shown vision in making strategic decisions, exercised highly adept political leadership and demonstrated clear commitment to the people and a strong sense of responsibility, which proved that he has been “worthy of the core of the CPC Central Committee and the whole Party”.

Under the model of guardianship, the rules of propriety that members of the party should follow emanate from the leader. As a tuned example, the general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, Xi Jinping, asserted that The Political Bureau members should take the lead in implementing the eight-point decision and pay close attention to how local governments and departments under their supervision carry out the rules (Annex 1). Within the model of guardianship, intra party democracy is an expression of democratic centralism-an additional trait of context in Chinese administration. Xi states that democratic centralism is the fundamental organizational principle and leadership system of the CPC, calling it an important feature that distinguishes Marxist political parties from other political parties. He has said the system integrates full intra-Party democracy and proper centralism, making it a scientific, sound and efficient system. The following is an example of intra-party democratic deliberation:

“Participants (Political Bureau members) deliberated on a report on the implementation of the eight-point decision by the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee since the 19 National Congress of the CPC before the Political Bureau members gave speeches one by one”.

Xi said efforts should be made to unify both democracy and centralism and truly transform the strength of democratic centralism into political, organizational, institutional and practical strengths of the Party. Thus, stressing the authority and centralized unified leadership of the CPC Central Committee, Xi defends that “many tough problems, which had been long on the agenda but never resolved, were solved, and many things, which had been wanted but never got done, were accomplished because of the unity within the Party”. Xi also defends that governing such a large party and country requires intraparty democracy, through democratic centralism. Xi also states that implementing democratic centralism is the common political responsibility of the whole Party and is primarily the responsibility of leading cadres of all levels, especially the Political Bureau members. Party officials, especially the leading Party officials, should mandate in their fighting spirit and enhance their competence, according to Xi.

The guardianship discourse, however, is today complemented with views that “democratic public administration and the rule of law are also values urgently needed by the public sector”, speaking of the need of democratic regeneration. This is more so after the Chinese political leaders advanced the concept of “New Normal” in 2014, responding to challenges such as a growth rate of gross domestic product that dropped below 8 per cent for the first time since 2000. Where “established models of government are facing a declining base of legitimacy and effectiveness [17].” This is also in line with the concept of New Era that has been written recently in the Chinese communist party constitution: “The new era concept provides an ontological foundation and a terminological starting point for the Chinese polity. Having been written into the CCP constitution, the new era ideology has far-reaching implications for China’s mode of governance, economy, society, and foreign policy [18].

Adding up into elements for context in Asia, Wolfgang Drechsler looks for states or country-like structures that use Buddhist economics as elements of importance. In his work, among diverse cases of Buddhist economies, Drechsler differentiates the “Unification of King and People” model in Yogyakarta. Drechsler finds Unification of King and People as a contextualized version of deliberative democracy [19]. There exist three elements in this Unification of King and People: Social justice, multiculturalism in a framework of tolerance, and a knowledge-based economy. In the analysis done by Drechsler, the figure of the Sultan delivers what public-policy specialists want to hear, in a contemporary way, including the cultural, traditional, identity creating, representational and spiritual offerings as Sultan. Drechsler emphasizes that legitimation is by consensus, both traditional and personal. Drechsler also points out that depending on context and the audience “both happiness and economic growth” are emphasized [20].

Main features of context in China from philosophical foundations;

• Confucian conception of the State as an extension of the family and other forms of social life

• Guardianship based on a paternalistic meritocracy

• Pursue of long term and collective interests

• Superior knowledge and virtue

• Responsibility and commitment as bases of legitimacy

• Legitimation by consensus (democracy as deliberation of the communist political party)

• Morally competent rulers

• Minben (people-as-the-basis)

• Political integrity of the party

• Eight point government conduct for improvement

• Democratic centralism, according to Xi Jingping definition

The challenge of effectiveness-when gross domestic product goes below 8 percent

Philosophical foundations of public administration in the West

Looking for context in public administration in the West we may go back to Aristotles. In Aristotles speculation, the state in general is the ultimate form of human organization, and it exists to satisfy the highest goals of human life. In this conception, the State belongs to a higher order as opposed to Confucian conceptions that see the state as an extension of the family and other forms of social life. Max Weber context for modern public administration is a bureaucracy, subordinated to political organs-elective organs in democratic systems, and to the law enacted by elective organs. Following Lu and Shi the liberal democracy discourse accentuates the use of institutional arrangements to reach collective decisions on public issues and ensure good governance. At the heart of these arrangements lie both competitive elections and institutionalised protection of political rights. The system not only allows people to press political leaders over policy concerns, but also grants them the right to replace the government through established procedures. In essence, within this discourse contemporary, democracy is presented at the very least as a government organised on the basis of a set of institutions that guarantee some basic freedoms and ensure people’s rights to participate, choose their leaders, and collectively make decisions for their society. More recently Jun has emphasized in his approach the active involvement of citizens in promoting public values [21]. Public administration is thus the result of a process of social construction, and the social construction of democratic public administration would entail employee participation, citizen involvement, empowerment and consultation are centre stage not just as outcome, but in the dialectical process of construing a public administration and an administrative theory where the emphasis in on the public in the administrative process.

Jun includes in his conception social design and two sides of public administration; the general public and the governmental sides of public administration. Social design would be evolutionary, an integrative process to build shared realities that could lead to a process of invention, evolution and self-governance. This contribution rests on an existentialist perspective, as noted by Ongaro.

Deliberative democracy in society is also a tool to be influential on government policy or action. It is a political philosophy has roots in Aristotles and later on, the enlightenment, based on a defence of democratic decision-making. Weymouth and Hartz- Karp propose three key governance principles to differentiate deliberative democracy in society from community consultation, empowered community engagement, and other forms of democracy and citizen participation analysed by Carson and Hartz-Karp (Table 1) [22-24].

| Deliberation/Weighing | Representation/Inclusion | Influence/Impactfulness |

|---|---|---|

| The group looks for a common good arriving at a publicly justified decision or conclusion that is based on the shared judgment. The search for common ground is important. Reaching consensus is desirable but not essential. Two elements are particularly relevant. The first is the use of randomly selected citizens who often knew little about the topic under deliberation or are politically inactive, but could clarify the values they held dear. This is found to be advantageous to deliberation, because participants are not cognitively or emotionally anchored to a position and hence they are open to potential attitude shifts on the topic. Within the Deliberation/Weighing governance mode is also the inclusion of stakeholders involved in, or affected by, the issue being deliberated, whose expertise and buy-in would be important. |

Representation is important: • As a form of democracy, the legitimacy claim to decide on behalf of a “demos” is definitional. • The deliberative desire to weigh all arguments and perspectives on an issue of importance to a “demos” drives a search for inclusion of those perspectives as another claim to (deliberative) legitimacy (in contrast with a pre-set policy agenda). Descriptive representation (demographic characteristic: e.g., age, gender, socio-economic status etc.); Random selection (often with stratification for demographic characteristics to maximise representativeness) is the most common method of achieving a decision-making group who reflect the diversity of outlooks (worldviews) within the general population. This diversity legitimacy boosts the claim that any decisions are made for the common good, since the group descriptively resembles the collective. |

A prior commitment by official decision-makers enables participants to exert influence-and to be seen as exerting influence-on policy development and decision-making about the matter being deliberated. This commitment can depart from serious consideration of recommendations with commitments of public responses. |

Table 1: Deliberative democracy by Weymouth and Hartz-Karp.

• The first key governance principle is Deliberation/Weighing; Participants in a deliberative democratic process in society weigh reasons and arguments for and against competing options using rationality and shared values, as stated by Greenhalgh and Russell [25].

• The second key governance principle is Representation/Inclusion; a form of democracy that pays particular attention to the deliberative communication mode.

• The third key governance principle is Influence/Impactfulness; most deliberative forums take place in the context of existing power structure and statutes and usually have to take account of this.

Although related, in the West there is a tradition to distinguish participatory democracy as a governance system from deliberative democracy. Participatory democracy involves a broad involvement of constituents in a political system. However, participatory democracy has had critics for the lack of focus on deliberation and collaboration. Deliberative democracy as a governance system has also shortcomings (Weymouth and Hartz-Karp); despite its successful implementation in many countries and improvements in methodology, it has yet to be scaled (both vertically and horizontally) and institutionalised, as Mansbridge recall [26]. The need to scale initiatives to improve their scope and reach, while addressing higher levels of complexity, has had to date only a limited success. And a further problem is to retain high-quality deliberation and containing costs. Institutionalisation is problematic, in part because most existing democratic power structures inherently limit the potential for co-decision-making between elected officials and their constituents, and in part because power is rarely conceded voluntarily.

Ongaro also brings about a different context, diverging from that resting on the mode of participation. It is based on radical positions emphasizing the minimal state as the aim of reforms or innovations in recent decades. These positions tend to “advance any form of common good and instead disparage the significance of any attempt to reform it, assuming the minimization of the state might itself lead to the betterment of the lives of the political community or the fittest to survive in the environment”.

Main features of context in the west. From philosophical foundations;

• Aristotles; State as ultimate form of human organization, it exists to satisfy the highest goals of human life.

• Weber; Modern public administration a bureaucracy subordinated to elective organs in democratic systems, and to the law enacted by elective organs.

• Institutional arrangements to reach collective decisions, based on competitive elections.

• Replacement of government through established procedures.

• Set of rights and institutions that guarantee basic freedoms and ensure people´s rights to participate choose their leaders and collectively make decisions.

• Active involvement of citizens in promoting public values.

• Social design evolutionary, with an emphasis on the public in the administrative process.

• Participatory and deliberative democracy in some cases

In the following section definitions of smart cities are provided before analysing public participation in public administration in China in a context of innovation in relation with its philosophical foundations.

The Chinese case and the smart city plan in Shanghai

Applying the concepts in former sections on philosophical foundations of public participation in public administration to the case of Shanghai, we would expect a context of guardianship discourse, together with what is called good governance an emphasis on moral cultivation, virtue and propriety, responsibility and commitment, brought about from Confucius teachings. To these traits we would also expect centralism and intraparty democracy understood as deliberation. When we analyse the general picture, however, Shanghai, and the Chinese case more broadly reflect a more diverse context, with the introduction of some pilots of deliberative democracy at the local level (Tong and He) [27]. He recalls that Chinese villagers or village representatives have monitored budgeting to ensure that village leaders collect money for public goods, distribute village income in a fair way and invest village money effectively since the early 1990s. This has been called ‘the openness of the village account’ and ‘the democratic management of the village account’. In 1991, the local People’s Congress in Shenzhen set up a budget committee in which deputies had an opportunity to examine the budget. In 1998, Hebei province introduced sector budgeting, meaning that partial budgets were disclosed to the people’s deputies of the People’s Congress for examination and deliberation. In 2004, Huinan Township in Shanghai undertook an experiment in public budgeting. In 2005 we found a step forward, with a First Chinese Deliberative Poll, an experiment of deliberative democracy, carried out in the town of Zeguo, Wenling City, Zhejiang Province (Fishkin) [28,29]. This experiment has been among the first world wide conducted by a government itself and actually implemented as public policy. Zeguo deliberative poll has been described as “the first case in modern times of fully representative and deliberative participatory budgeting.” Deliberative polling is “a method of consulting people on public affairs. By randomly selecting participants from the population and soliciting discussions on key policy issues, it serves as an effective way for the government to learn about people’s needs and promote innovative problem solving” [30].

There exist some other limited experiments on the involvement of the public in policy making, and human-centred smart city development in China, such as the one carried out in Guiyang Municipal Government and led by UNDP (2017). These experiments follow the path suggested by Premier Li Keqiang on March 9, 2017 that commits the government to “exploring new forms of social governance” which is elaborated as improving self-governance, community governance and the role of social organisations as well as protecting legal rights, especially of vulnerable groups including women, children and the elderly. As Zhou remarks, many research works find difficulties to improve the bureaucratic structure for developing countries dedicated to promoting the democratic consultation system such as public participation [31-34]. However, the former examples have been set in place. More recently we see new developments, as pointed by Mittelstaedt in his review of the report to the 19th party congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Mittelstaedt stresses that there is a change in context under way that we may see in what he calls social governance. For instance, legal scholars Jiang Ming’an and Yang Jianshun have elaborated on the report’s idea of “together constructing, governing, and sharing”. This idea would rest in the acknowledgement that society is divided into diverse communities that have a wide variety of interests and needs: “Social governance innovation therefore stresses the need for communities to construct and govern themselves, while the government provides them with guidance and public goods such as policing and healthcare (Mittelstaedt)”. The legal system is also affected, and a variety of legal scholars argue that the new era requires a novel approach to the law: Knowledge of the law is no longer enough; “belief in the rule of law” is also needed (Mittelstaedt). The report expressed this idea using the phrase “rule of law cultivation”. The aim is not only for people to passively obey laws, but also to actively deploy and consciously protect them. Thus, legal scholars argue that the task of the newly established leading group for advancing lawbased governance is to coordinate the propagation of the law, the education of citizens, and legal work.

If we focus on our applied case, Shanghai, the local government has declared to firmly support the Party’s reform efforts and has been actively promoting the implementation of reform measures in many respects, including coordinating with related state departments and local Party Committees and governments to promote the launching and implementation of general plans and policies. We also find as global aim a deepening industry reform, and unleash of market forces. The General Office of the Central Committee of the CPC and General Office of the State Council Print and Issue the Opinions on Further Strengthening the Work of the so called Highly Skilled Talents. Following the Eight point regulation, municipal leaders were urged to improve research and inspection at grassroots level, cut unnecessary meetings, regulate activities related to foreign affairs, and make news reports on the local government and the Party more efficient in a bid to win the trust and support from the people: “We must implement the new rules. If we only talk the talk, we will harvest the opposite result and incur aversion from the people,” said Han Zheng, Party chief of Shanghai municipal Party committee in 2012. After Han, Yang Xiong and Ying Yong have been the following appointed mayors of Shanghai. This shows a general context for public policy and innovation that continues to give the administration, and the party within it, a central role. However, some experiments have been carried out with deliberative democracy. In response to the 2014 No.1 Research Program of Shanghai Municipal Party Committee, a Deliberative Poll was held at Puxing Sub-district in Pudong New District, Shanghai on May 31st, 2015. Advised by the Center for Comparative Urban Governance (CCUG) at Fudan University, the Deliberative Poll invited ordinary citizens to participate in selecting projects that receive “Neighborhood Committee Selfgovernance Fund”. The preparation and implementation of this project-starting from training moderators, random sampling of residents, and ending with Deliberation Polling-spanned over six months. The project offers an example of putting theories of deliberative democracy into practice in urban China.

The design and implementation of the smart city plan for the city of Shanghai, however, is closer to the model of guardianship discourse. Fifty-one urban areas with plans and specific goals addressing smart cities by 2011 (Liu, Peng) draw by the political party, where the focus on a design from above:

“Attention must be paid to the cultivation and management of talented persons and professionals... education and training... build a high-end talent platform with famous university and scientific research institutes and carry out a mode of cooperation between colleges...... local industries,...... with the complementary of vocational training schools, providing coordination for producing, learning, studying, and researching (Liu and Peng)”[35].

In Shanghai the first three-year plan attempted to render more support to people able to participate on building the smart city. However, to do so the mechanics have been “introducing leadership, compound and professional talents,” to raise talent for the development of “smart city building,” and coordination of innovation of firms, universities, research institutions and users for the new generation of IT industry, including cloud computing and the Internet of things. The context included what was described as a sound environment, meaning professional forums, conferences and exhibitions. The sound environment attempted that the whole society supported the smart city developments. The smart city plan includes the participation of local governments and universities, both led by officials from the communist party. Cooperation is open to local governments, universities and foreign firms, under the same model of guardianship. Japanese firms as well as IBM, for instance, have developed strong win-win alliances with local governments. In all cases the party elected officials have a stronghold of executive power, with higher level governments decentralizing tasks to local authorities. The urban regions adopt a mode of governance in which the local governments lead the smart city projects. Local governments are also the node for foreign firms interested in local collaboration.

Context is based on the strengthening of organization and leadership of public administration. There is a municipal leading group responsible for building the smart city, and a unified deployment of the work on smart city construction. This group has under her supervision an office responsible for daily coordination of the work related to the smart city overarching project. Shanghai also set up a Smart City Expert Committee and an expert policy advisory mechanism. Together with organizations considered relevant they also set up a Smart City Promotion Center. The relevant commissions, offices and bureaus are responsible for detailed implementation of the tasks in different areas. In accordance with their respective responsibilities. Districts and counties within the city also set up corresponding mechanisms to propel smart city building in their respective areas under the deployment of the city. Citizen engagement mechanisms have been designed to engage citizens through service trials, training, crowdsourcing and gamification. For the Shanghai Pudong New Area services have included an evaluation of the citizens through assessment frameworks. Training has been understood as a tool for participation, and under the smart Pudong people plan 50,000 citizens have been trained on the use of smart services. Shanghai, as all Chinese smart cities pilots have formal leadership structures with senior officials responsible (Mayor or Vice Mayor), responsible for the overall delivery of the smart city program. Stakeholders are included in the smart city realization (China Academy). As Riva Sanseverino contends a major difference in China comes with respect to Open Data in urban contexts [36]. In China data is not open. Data is property of the Chinese government or of big IT companies. Moreover, in most cases, there is no compatibility among data deriving from different departments, making data sharing hard. Data is not publicly available, creating a problem to residents participation in using data to deploy novel products and services. Therefore in this dimension, Chinese pilot cities have different foundations for public participation in public administration, as compared to cases in the west [37-41].

From the specific case of Shanghai, what can we say of the philosophical micro foundations of public participation in China? We did find policies in tune with the guardianship discourse, responsibility and commitment from above, justified on moral cultivation, virtue and property, brought about from Confucius teachings. We also found centralism, intraparty democracy-understood as deliberation, and some experiments with democratic deliberation under deliberative poll schemes [45-50].

From the analysis of our case, the public participation framework in public administration in the case of Shanghai, a different model to understand and explain innovation is proposed. This model makes endogenous the foundations for change, and allows for comparisons with the west (Table 2).

| Country | Legitimacy based guardianship | Legitimacy based on democracy (direct appointment of leader through elections) | Democracy as deliberation | Rule of law | Democratic public administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| West | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 2: The Gil dashboard; Endogenous foundations for change.

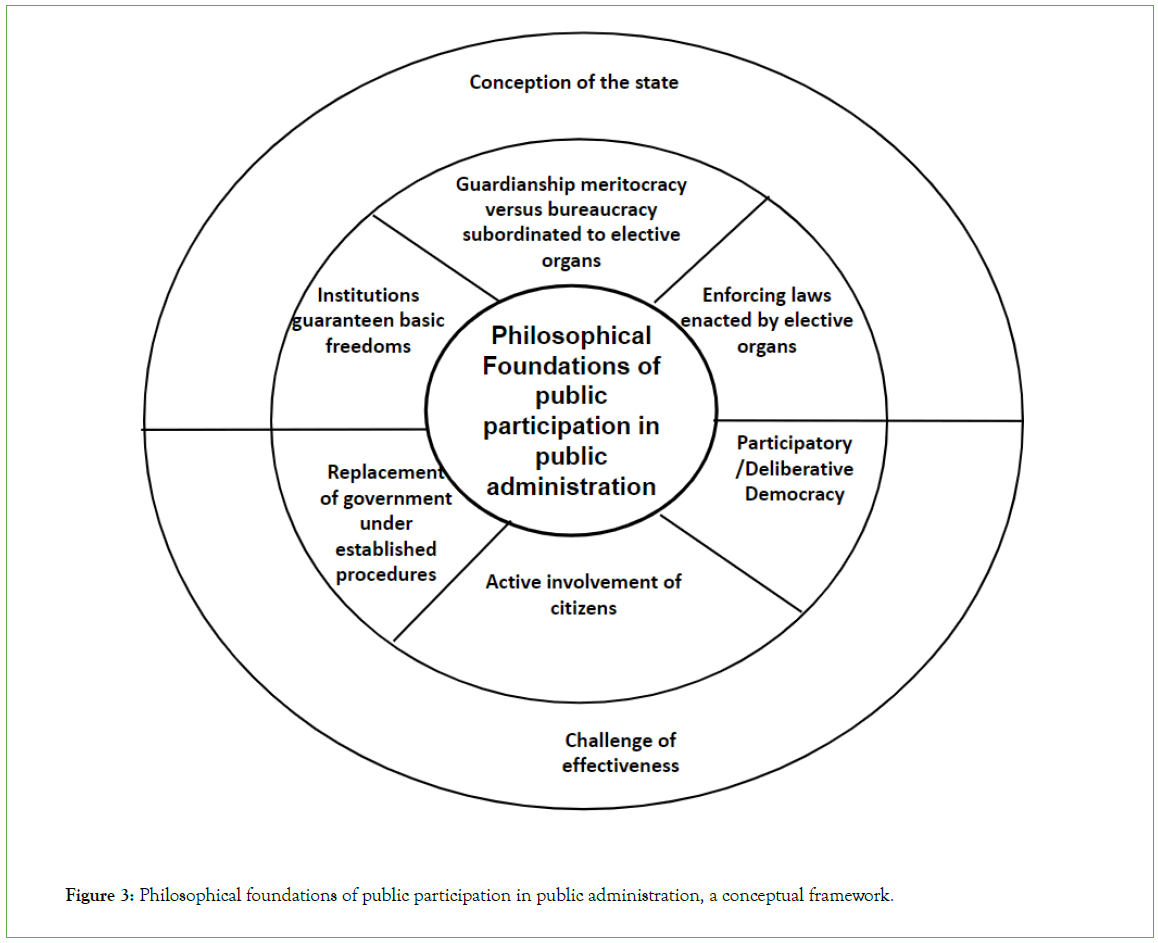

One possible conceptual model for context in public administration from a philosophical point of view could be the following shown in Figure 3. The model does situate neither innovation nor technology at the center of the equation, as they do not preclude differences in context. It focuses on the political administrative regime, on processes (Pollitt and Bouckharet), on the top-down, bottom up perspectives and the legal dimension [51].

Figure 3: Philosophical foundations of public participation in public administration, a conceptual framework.

Results and Discussion

Analysis and findings from our case

In this work the main question of the philosophical enquiry has been what are the philosophical foundations of public participation in public administration in the Chinese context Our work has so far confirmed the hypothesis that foundations of public participation in public administration are different in the Chinese context from the west. The confirmation of this hypothesis rests on the research, showing difficulties in the standardization of concepts for public administration in China and the west: The fact that underlying assumptions and features of public participation in both contexts might not be unproblematically stated brings philosophy to the fore, and with a particular strength as a previous stage of understanding previous to organizing what is known [52,53].

We have seen that differences in practice are broader than previous theoretical models of public administration suggest, while political philosophy has helped us to shed light to understand these differences. In our exploration of context in China and the west we have first stressed these main differences as philosophical points of departure. We have reviewed context in public administration focusing on the philosophical foundations of public participation, revisiting context in China and western countries. In the case of China context is provided by the Confucian conception of the State as an extension of the family and other forms of social life. There is an emphasis on the concept of guardianship based on a paternalistic meritocracy. Together with this, the stress on moral cultivation of competent rulers, virtue and propriety, responsibility and commitment of the leadership, brought about from Confucius teachings. Next to these traits, we found the pursuing of long term interests, the superior knowledge and virtue expected from rulers, responsibility and commitment as basis of legitimacy, and legitimation by consensus, where democracy is understood as deliberation within the Communist party. Thus, what is termed as democratic centralism and intra-party democracy understood as deliberation are bases to provide for the context of good governance? Recent ruling stresses the political integrity of the party, and a new eight point government conduct for improvement. More recently, however, we also find voices defending democratic public administration and the rule of law as values urgently needed by the public sector (Jing and Osborne). This is more so in the light of the concept of “New Normal” brought about by political leaders in 2014, responding to challenges such as a decreasing growth rate of gross domestic product, dropping below 8 per cent for the first time since 2000. A new context in need of a base of legitimacy and effectiveness (Jing and Osborne). Our study of the case of smart city policies in Shanghai might be explained under this context for the analysis. We have also found innovations related to the introduction of democratic deliberation under deliberative poll schemes [54-60].

In the case of the West, philosophical foundations take us to Aristotles and the conception of the State as the ultimate form of human organization, as it would exist to satisfy the highest goals of human life. More recently, the reference to Max Weber, defining context for a modern public administration as a bureaucracy subordinated to political organs elective organs for the democratic systems, and to the law also enacted by elective organs. Principles of legitimation lie in the mixed formula; subordinated public administration+elected organs+rule of law, and this mixed formula answers challenges such as those posed by Rodriguez and Long among bureaucracy and innovation, rigidity and flexibility from their 20 empirical case analysis from both America and Europe [37]. We find a stress on institutional arrangements based on competitive elections to reach collective decisions; the replacement of government through established procedures; a set of rights and institutions that guarantee basic freedoms and ensure people’s rights to participate, choose their leaders and collectively make decisions; the active involvement of citizens in promoting public values; and more recently an approach to social design as something evolutionary. Examples of participatory and deliberative democracy are also found. For the West, Ongaro has raised the importance of ideas such as the radical positions defending the minimal state, assuming the minimization of the state might itself lead to the betterment of the lives of the political community which also give context to change and innovations in public administration. As we have shown, these positions create different contexts and approaches for the legitimation of public administration and their operation [61-68].

A dashboard for an endogenous foundation for change in public administration has been proposed (the Gil Dashboard), including legitimacy based guardianship, legitimacy based on democracy with appointments through elections, democracy as deliberation, the rule of law and democratic public administration. Both countries showed to fare differently on these grounds and allowing cross comparisons. This model shows specific differences in contexts in China and the west [38-45].

Conclusion

The work shows how the philosophical foundations of public participation in China and the west diverge. We found both contexts referring to democracy as an ‘essentially contested concept’ while (democratic) innovation is interpreted in a number of different ways across countries and policy areas, as recalled by Estub and Escobar. Thus, local differences are fundamental with regard to the institutional foundations of public participation in public administration, and we have shown so for a particular applied case in Shanghai. This work makes a contribution on how cultural, political and administrative contexts shape public administration and public policies from a philosophical point of view. However, this research also shows that more works are needed as case studies tackling context for China and from enriched comparative perspectives.

References

- Kenny A. A new history of Western philosophy. OUP Oxford. 2012.

- Ongaro E, Van Thiel S, editors. The Palgrave handbook of public administration and management in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 2018.

- Ongaro E. Philosophy and public administration: An introduction. Edward Elgar Publishing. 2020.

- De Vries H, Bekkers V, Tummers L. Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public administration. 2016;94(1):146-166.

- Pollitt C. Hospitals and the dynamics of multiple contexts. InContext in Public Policy and Management 2013.

- Pollitt C, Bouckaert G. Public management reform: A comparative analysis-into the age of austerity. Oxford university press. 2017.

- Conteh C. Public management in an age of complexity: regional economic development in Canada. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2012.

- Juliani F, de Oliveira OJ. State of research on public service management: Identifying scientific gaps from a bibliometric study. Int J Inf Manage. 2016;36(6):1033-1041

- Komninos N. Intelligent cities: towards interactive and global innovation environments. Int. J. Entrepreneurship Innov. 2009;1(4):337-355.

- Allwinkle S, Cruickshank P. Creating smart-er cities: An overview. J. Urban Technol. 2011;18(2):1-6.

- Hsiao CH, Yang C. The intellectual development of the technology acceptance model: A co-citation analysis. Int J Inf Manage. 2011;31(2):128-136.

- Elstub S, Escobar O. A Typology of Democratic Innovations. Paper for the Political Studies Association’s Annual Conference, 10th-12th 2017.

- Elstub S. The third generation of deliberative democracy. Political studies review. 2010;8(3):291-307.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement sci. 2010 ;5(1):1-9

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu J, Shi T. The battle of ideas and discourses before democratic transition: Different democratic conceptions in authoritarian China. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2015;36(1):20-41.

- Xinhua, 2018. CPC meeting underlines core status of Xi. December 27. Retrived March 13th 2019.

- Jing Y, Osborne SP. Public service innovations in China: An introduction. InPublic service innovations in China. 2017:1-24.

- Mittelstaedt, J C. New era between continuity and disruption. retrieved March 21rs, at: China’s “New Era” with Xi Jinping characteristics.

- Drechsler W. The reality and diversity of Buddhist economics. Am J Econ Sociol. 2019;78(2):523-560.

- Drechsler W. The Reality and Diversity of Buddhist Economics (With Case Studies of Thailand, Bhutan and Yogyakarta). TUT Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance. 2016.

- Jong S. Social Construction of Public Administration, The: Interpretive and Critical Perspectives. SUNY Press. 2019.

- Weymouth R, Hartz-Karp J. Principles for integrating the implementation of the sustainable development goals in cities. Urban Science. 2018;2(3):77.

- Hartz-Karp J, Carson L, Briand M. Deliberative democracy as a reform movement.

- Carson L, Hartz-Karp J. Adapting and combining deliberative designs: Juries, polls, and forums. The deliberative democracy handbook: Strategies for effective civic engagement in the twenty-first century. 2005:120-38.

- Greenhalgh T, Russell J. Evidence-based policymaking: a critique. Perspect Biol and Med. 2009;52(2):304-18.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mansbridge J, Bohman J, Chambers S, Christiano T, Fung A, Parkinson J, et al. A systemic approach to deliberative democracy. Deliberative systems: Deliberative democracy at the large scale. 2012:1-26.

- Tong D, He B. How democratic are Chinese grassroots deliberations? An empirical study of 393 deliberation experiments in China. Jpn. J. Political Sci. 2018;19(4):630-642.

- Fishkin J. When the people speak: Deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oup Oxford. 2009.

- Fishkin JS, He B, Luskin RC, Siu A. Deliberative democracy in an unlikely place: Deliberative polling in China. British Quart J Polit Sci. 2010;40(2):435-448.

- Fuguo H, Jing H, Xu Y. Making Democracy Practicable in China: The first Deliberative Polling on Urban Governance in Shanghai. The Paper. Accessed on March 20th 2019.

- Zhou Y, Hou L, Yang Y, Chong HY, Moon S. A comparative review and framework development on public participation for decision-making in Chinese public projects. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019;75:79-87.

- Xie LL, Xia B, Hu Y, Shan M, Le Y, Chan AP. Public participation performance in public construction projects of South China: A case study of the Guangzhou Games venues construction. J. Proj. Manag. 2017;35(7):1391-1401.

- Tang BS, Wong SW, Lau MC. Social impact assessment and public participation in China: A case study of land requisition in Guangzhou. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2008;28(1):57-72

- Yang S. Public participation in the Chinese environmental impact assessment (EIA) system. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2008;10(01):91-113.

- Liu P, Peng Z. Smart Cities in China, IEEE Computer Society Digital Library.

- Riva Sanseverino E, Riva Sanseverino R, Anello E. A cross-reading approach to smart city: A european perspective of chinese smart cities. Smart Cities. 2018; 2;1(1):26-52.

- Rodriguez E, Long F. Laboratorios de innovación: burocracia y sociedad frente al fenómeno de la experimentación en el sector público. Comparando experiencias de ambos lados del Atlántico. InVI Congreso Internacional sobre Democracia organizado por la facultad de Ciencia Política y relaciones Internacionales de la Universidad de Rosario. Rosario 2018;10-13.

- Cortés-Cediel ME, Gil O, Cantador I. Defining the engagement life cycle in e-participation. InProceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age 2018;1-2

- Gil O, Navío J, Pérez de Heredia M. Cómo se gobiernan las ciudades? Ciudades inteligentes. Casos comparados: Shangái, Iskandar, ciudades en Japón, Nueva York, Ámsterdam, Málaga, Santander y Tarragona. Silva Editorial; 2015.

- Gil O, Cortés-Cediel ME, Cantador I. Citizen participation and the rise of digital media platforms in smart governance and smart cities. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2019;8(1):19-34

- Elstub S, Escobar O. A Typology of Democratic Innovations. Paper for the Political Studies Association’s Annual Conference, 10th-12th 2017.

- Elstub S. The third generation of deliberative democracy. Political studies review. 2010 Sep;8(3):291-307.

- Abellán J, Artacho PA. Burocracia y administración pública. el paradigma burocrático y el pensamiento weberiano. In Democracia, Gobierno y Administración Pública contemporánea 2020; 43-64.

- Sáez MA, Nieto LL, del Campo ME. Procesos de transición a la democracia: estudios comparativos. Instituto Interamericano de Derechos Humanos, Centro de Asesoría y Promoción Electoral. 1992.

- Barreda M, Ruiz-Rodríguez LM, editors. Análisis de la política: enfoques y herramientas de la ciencia política. Huygens Editorial. 2016.

- Chambers S. Deliberative democratic theory. Annual review of political science. 2003;6(1):307-326.

- de Lima Gete MB, del Campo García ME. Buen gobierno, rendimiento institucional y participación en las democracias contemporáneas. Sistema: revista de ciencias sociales. 2008(203):55-69.

- Dryzek JS. Deliberative democracy and beyond: Liberals, critics, contestations. Oxford University Press on Demand. 2002.

- Franzé J. ̈Que es la politica?:Tres respuestas: Aristóteles, Weber y Schmitt. Los libros de la catarata. 2004.

- Gastil, J, Richards, R.C. Deliberation. In International Encyclopedia of Political Communication; Mazzoleni, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK. 2016.

- García Guitián E. El significado de la representación política. Anuario de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. 2004:109-120.

- Gutmann, A.; Thompson, D.F. 1998. Democracy and Disagreement; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Thompson DF. Deliberative democratic theory and empirical political science. Rev. Political Sci. 2008.

- He B. Civic engagement through participatory budgeting in China: Three different logics at work. Public administration and development. 2011;31(2):122-133.

- Li W, Liu J, Li D. Getting their voices heard: Three cases of public participation in environmental protection in China. J Environ Manage. 2012;98:65-72.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin Y. A comparison of selected Western and Chinese smart governance: The application of ICT in governmental management, participation and collaboration. Telecommunications policy. 2018;42(10):800-809.

- Moreno del Rio C. Los fundamentos de la política: la noción de política, las teorías sobre el concepto de poder y el dilema legalidad vs. legitimidad política. InAnálisis de la política: enfoques y herramientas de la ciencia política 2016:23-44.

- Nabatchi T, Gastil J, Weiksner GM, Leighninger M. Democracy in motion: Evaluating the practice and impact of deliberative civic engagement. Oxford University Press. 2012.

- Nam T, Pardo TA. Smart city as urban innovation: Focusing on management, policy, and context. InProceedings of the 5th international conference on theory and practice of electronic governance. 2011: 185-194.

- Ciudadana P, España EI, Del Estado AG. Participación y crisis institucional. Participación ciudadana: Experiencias inspiradoras en España. 2018.

- Sanchez Medero G, Pastor Albaladejo G. The quality of participatory processes in the urban redevelopment policy of Madrid city council.2019.

- Seaker Chan Center SI. Public participation in China and the West.

- Wences MI. Lecturas de la sociedad civil. Un mapa contemporáneo de sus teorías. Republicanismo cívico y sociedad civil. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. 2007.

- Smart EC, Cooperation GC. Comparative study of smart cities in Europe and China. Current Chinese Economic Report Series, Springer. 2014.

- Eight point regulation. Retrived March 13th 2019 at Public participation in China and the West.2019.

- General Office of the Central Committee of the CPC and General Office of the State (China).

- China UN. Smart cities and social governance: Guide for participatory indicator development. United Nations Development Programme in China, Beijing, China.

- Shan XZ. Attitude and willingness toward participation in decision-making of urban green spaces in China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012;11(2):211-217.

Citation: Gil O (2023) Philosophical and Public Administration in China and Western Countries. Intel Prop Rights. 11:216.

Copyright: © 2023 Gil O. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.