Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- CiteFactor

- Cosmos IF

- Scimago

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Electronic Journals Library

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Directory of Abstract Indexing for Journals

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Proquest Summons

- Scholarsteer

- ROAD

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2025) Volume 17, Issue 7

Pediatric and Adolescent Considerations in Antiretroviral-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Mechanisms, Risks, Monitoring and Management

Fahmida Akter1, Hure Jannat Jyoti2, Sophia Hossain3, Sadia Afroz4, Eshita Akter4, Sadman Radit Aurnab5, Aqib Hossain Khan6 and Imtiaj Hossain Chowdhury6*2Department of Pharmacy, University of Asia Pacific, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Department of Pharmacy, ASA University Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Department of Pharmacy, Gono Bishwabidyalay, Dhaka, Bangladesh

5Department of Pharmacy, Bangladesh University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

6Department of Pharmacy, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Received: 11-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. BLM-25-29898; Editor assigned: 15-Sep-2025, Pre QC No. BLM-25-29898 (PQ); Reviewed: 29-Sep-2025, QC No. BLM-25-29898; Revised: 11-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. BLM-25-29898 (R); Published: 18-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.35248/0974-8369.25.17.781

Abstract

The scale-up of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) has transformed pediatric and adolescent Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection into a manageable chronic disease. Children living with HIV now initiate therapy in infancy and remain on lifelong treatment, resulting in cumulative exposure to antiretrovirals and their toxicities. Hepatotoxicity, ranging from asymptomatic transaminase elevations to severe Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI), represents one of the most clinically significant adverse effects of ART. Although hepatotoxicity has been extensively described in adults, pediatric populations face unique vulnerabilities due to developmental pharmacokinetics, nutritional deficiencies, coinfections, and evolving metabolic risk factors during adolescence. This review synthesizes current evidence on mechanisms of ART-related hepatotoxicity, age-specific susceptibilities, and drug class–associated risks in children and adolescents. It further explores the influence of coinfections such as hepatitis B and tuberculosis, emerging challenges including Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), and the role of genetic polymorphisms in shaping hepatotoxicity risk. Current recommendations for screening, monitoring, and management are summarized, with a focus on adapting adult-derived protocols to pediatric practice. Gaps in evidence, especially in low and middle-income countries, and priorities for future research including pharmacogenomics, longitudinal studies, and non-invasive biomarkers are highlighted. Pediatric and adolescent patients with HIV represent a vulnerable population in whom hepatotoxicity is both preventable and manageable if recognized early. Optimizing monitoring strategies and developing safer regimens are essential to safeguard long-term liver health in the next generation of people living with HIV.

Keywords

HIV; Pediatrics; Adolescents; Antiretroviral therapy; Hepatotoxicity; Drug-induced liver injury

Introduction

The global scale-up of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) has markedly reduced HIV-related morbidity and mortality, including in pediatric populations. According to UNAIDS, an estimated 1.4 million children under 15 years were living with HIV in 2023, with approximately 1 million receiving ART [1,2].

The widespread adoption of Dolutegravir (DTG)-based regimens has further improved viral suppression and resistance outcomes in children and adolescents [3]. However, lifelong ART exposure beginning in infancy introduces the potential for cumulative drug toxicity, particularly hepatotoxicity. Children and adolescents living with HIV often require decades of continuous therapy, which increases the likelihood of liver injury from direct drug toxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, or metabolic complications over time [4]. Moreover, early initiation of ART may predispose patients to long-term hepatocellular stress, compounded by potential coinfections (e.g., HBV, HCV) and lifestyle factors that emerge in adulthood. [5] Thus, the cumulative burden of ART exposure represents a significant concern for lifelong liver health in people living with HIV.

Hepatotoxicity is a well-recognized complication of ART and includes asymptomatic transaminase elevations, immunemediated hypersensitivity hepatitis, mitochondrial hepatopathy, steatosis, and fulminant hepatic failure [6]. While much of the evidence base arises from adult studies, children and adolescents have distinct risk profiles. Developmental differences in hepatic enzyme maturation, nutritional vulnerabilities, and coinfections such as Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Tuberculosis (TB) can magnify susceptibility to Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI). Furthermore, adolescents face emerging risk factors such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), which intersect with ART-related hepatotoxicity [7,8]

While Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) has dramatically improved survival and quality of life for children and adolescents living with HIV, its lifelong administration presents a dual challenge: Sustaining virologic control while minimizing cumulative toxicity. Hepatotoxicity, in particular, has emerged as a significant concern in pediatric populations exposed to ART from infancy. The interplay of immature hepatic enzyme systems, coinfections such as Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Tuberculosis (TB), and nutritional deficiencies may exacerbate the risk of Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) in children [9,10]. In adolescents, additional risk factors including obesity, insulin resistance, and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) compound these vulnerabilities [10,11]. These realities underscore the importance of age-appropriate pharmacovigilance, with regular liver function monitoring, individualized regimen selection, and the availability of less hepatotoxic alternatives. Integrated care approaches that address nutritional support, screening for metabolic syndrome, and proactive management of coinfections are essential to reduce the long-term burden of ART-related liver injury [12]. As ART initiation now routinely begins in infancy and continues lifelong, ongoing research into safer formulations, pediatricspecific dosing guidelines, and predictive biomarkers for hepatotoxicity is critical to ensuring durable, safe, and effective HIV treatment across the pediatric age spectrum.

Despite its clinical relevance, pediatric ART hepatotoxicity remains under-characterized. Most current monitoring guidelines are adapted from adult data, with limited pediatricspecific evidence. This review aims to synthesize available data on ART-induced hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents, emphasizing mechanisms, age-related vulnerabilities, drug class– specific risks, comorbid conditions, monitoring, and management strategies.

Materials and Methods

This review followed a systematic approach to identify, evaluate, and synthesize evidence on antiretroviral therapy (ART)–induced hepatotoxicity in pediatric and adolescent populations. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Search terms included combinations of: “HIV,” “children,” “adolescents,” “antiretroviral therapy,” “hepatotoxicity,” “drug-induced liver injury,” “NNRTI,” “PI,” “INSTI,” “NRTI,” “nevirapine,” “dolutegravir,” “liver enzymes,” “NAFLD,” and “toxicity.”

Eligible studies included randomized trials, observational cohorts, pharmacokinetic studies, case series, and systematic reviews evaluating hepatic outcomes in individuals receiving ART. Publications were excluded if they lacked liver-related outcomes, or were commentaries without primary data. Titles and abstracts were screened, followed by full-text review of potentially relevant articles. Data extraction focused on hepatotoxicity mechanisms, incidence, drug-specific risks, comorbidities, monitoring practices, and long-term outcomes.

Findings were synthesized qualitatively due to heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and outcome definitions. Evidence was integrated to provide a comprehensive assessment of pediatric specific hepatotoxicity patterns and clinical implications.

Mechanisms of antiretroviral-induced hepatotoxicity

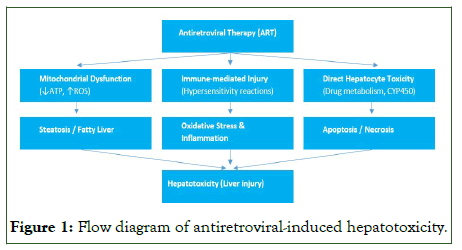

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) has significantly improved survival and quality of life in people living with HIV. However, hepatotoxicity remains one of its most clinically relevant adverse effects, contributing to treatment interruptions and morbidity [13]. The mechanisms of antiretroviral-induced liver injury are multifactorial, involving direct drug toxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, and altered hepatic metabolism. These processes may lead to steatosis, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation, ultimately culminating in hepatocellular injury. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for early detection, prevention, and management of ART-related liver complications (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow diagram of antiretroviral-induced hepatotoxicity.

Direct hepatocellular toxicity: Many antiretrovirals undergo hepatic metabolism, and toxic metabolites can directly injure hepatocytes. Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs), particularly nevirapine, are associated with hepatocellular necrosis due to reactive intermediate metabolites [14]. Protease Inhibitors (PIs), metabolized by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes, may cause hepatotoxicity through direct cytotoxicity and metabolic disturbances.

Mitochondrial dysfunction: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) are implicated in mitochondrial hepatotoxicity. Older NRTIs such as Stavudine and Didanosine inhibit mitochondrial DNA polymerase-γ, leading to impaired oxidative phosphorylation, lactic acidosis, and hepatic steatosis [15]. Although these agents are largely phased out, their longterm use in older pediatric cohorts highlights the importance of cumulative toxicity.

Immune-mediated injury: Idiosyncratic, immune-mediated liver injury occurs with certain antiretrovirals. Abacavir hypersensitivity reaction, strongly associated with the HLAB*57:01 allele, may present with hepatitis alongside systemic symptoms [16]. Nevirapine can also trigger immunoallergic hepatitis, particularly within the first 6–12 weeks of initiation, and appears more frequent in younger children and females [17].

Metabolic and steatotic injury: Protease inhibitors and Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs), particularly dolutegravir, are associated with weight gain and metabolic derangements. These changes predispose to NAFLD, an increasingly recognized cause of liver morbidity in adolescents living with HIV. As these individuals transition into adulthood, the interplay of ART, obesity, and hepatic steatosis becomes an increasingly important concern for long-term liver health [18,19].

Drug–drug interactions: Children with HIV often receive concomitant therapies, including TB drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin), antifungals, and anticonvulsants. These agents may potentiate ART hepatotoxicity through overlapping toxicities or cytochrome P450–mediated interactions [20].

Age-related vulnerabilities

Children and adolescents experience hepatotoxicity differently from adults due to developmental and contextual factors.

Immature hepatic enzyme systems: Neonates and young children exhibit delayed maturation of hepatic phase I (CYP450) and phase II (Glucuronidation, Sulfation) enzymes. This enzyme immaturity impairs drug clearance and predisposes to accumulation of parent compounds or toxic metabolites, thereby increasing vulnerability to hepatotoxic injury [21]. Clinically, this risk is exemplified by drugs like Nevirapine and Efavirenz, which have been associated with significant liver toxicity stemming from immune-mediated injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress, and impaired bile acid transport [22].

Nutritional status: Malnutrition, still common in many HIVendemic regions, compromises hepatic resilience. Protein-energy malnutrition impairs detoxification pathways, while micronutrient deficiencies (vitamin A, selenium, zinc) exacerbate oxidative stress [23]. Conversely, in high-income settings, rising rates of obesity in HIV-infected adolescents contribute to metabolic liver injury.

Hormonal and metabolic changes in adolescence: Puberty introduces hormonal fluctuations and shifts in body composition that alter drug pharmacokinetics. Increased insulin resistance and lipid abnormalities during adolescence interact with ARTassociated metabolic effects, compounding liver risk [24].

Cumulative lifetime exposure: Unlike adults who initiate ART later, children are exposed from birth or early infancy, leading to decades of potential drug–liver interaction. Even subclinical injuries in early life may predispose to fibrosis, cirrhosis, or NAFLD in adulthood [25].

Adherence and behavioral risk factors: Adolescents face unique challenges, including poor adherence, alcohol or substance use, and irregular health service utilization. These factors increase the likelihood of treatment interruptions, regimen switches, and repeated liver insults (Table 1) [26].

Category |

Risk factor |

Notes/Examples |

Age-related [27] |

Immature hepatic enzymes |

Slower clearance of NNRTIs in neonates/young children |

Pubertal hormonal changes |

Altered drug metabolism, increased metabolic risk |

|

Nutritional [29] |

Malnutrition |

Impaired hepatic detoxification, oxidative stress |

Obesity/metabolic syndrome |

NAFLD in adolescents, worsened by PIs/INSTIs |

|

Drug-related [27-29] |

NRTIs (Stavudine, Didanosine) |

Mitochondrial toxicity, lactic acidosis |

NNRTIs (Nevirapine) |

Hypersensitivity hepatitis, especially in young children |

|

PIs/INSTIs |

Dyslipidemia, weight gain, steatosis |

|

Comorbidities [30] |

HBV/HCV co-infection |

Increased hepatotoxicity risk with ART |

TB co-treatment |

Isoniazid/rifampicin overlapping toxicity |

|

Genetic [31] |

HLA-B*57:01 allele |

Abacavir hypersensitivity with hepatitis |

CYP450 polymorphisms |

Altered NNRTI metabolism |

|

Behavioral [32] |

Poor adherence, alcohol/substance use |

Repeated hepatotoxic insults, treatment interruptions |

Table 1: Key risk factors for antiretroviral-associated hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents.

Drug class–specific hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs): NRTIs form the backbone of pediatric ART regimens. Older NRTIs such as Stavudine (d4T) and didanosine (ddI) are well known for mitochondrial toxicity, leading to hepatic steatosis and lactic acidosis [33]. Although these agents are no longer recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and have been phased out of most programs, many children initiated on them in earlier years may still face long-term hepatic consequences. Newer NRTIs such as Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF), Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF), Lamivudine (3TC), and Abacavir (ABC) are considerably safer, but occasional hepatotoxicity has been documented. Abacavir carries the risk of hypersensitivity hepatitis in HLA-B*57:01–positive individuals, although this allele is less prevalent in African populations [31].

Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs): Nevirapine remains one of the most studied causes of pediatric ART-related hepatotoxicity. It is strongly associated with immune-mediated hepatitis, typically within 6–12 weeks of initiation, particularly in children under two years, females, and those with higher CD4 counts at ART initiation [34]. Clinical trials and cohort studies have reported hepatotoxicity rates of up to 8–10% in pediatric populations. Efavirenz, now more common in adolescents, is generally safer but may cause mild transaminase elevations [35].

Protease Inhibitors (PIs): Ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (LPV/r) was historically the cornerstone of first-line pediatric ART [36]. PIs are associated with metabolic complications including hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance, which predispose to secondary NAFLD [37]. Direct hepatotoxicity is less common but has been observed, especially in the presence of HBV or HCV co-infection. Darunavir, increasingly used in second-line therapy, has a relatively favorable hepatic safety profile but requires monitoring [38].

Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs): Integrase inhibitors such as Dolutegravir (DTG) and Bictegravir (BIC) are now preferred first-line options for children and adolescents due to high efficacy and tolerability [39,40]. Clinical trials, including IMPAACT P1093 and ODYSSEY, demonstrated good hepatic safety, with minimal grade 3–4 transaminase elevations. However, INSTIs are linked to weight gain and metabolic alterations, raising long-term concerns about NAFLD in adolescents [41]. Pediatric-specific longitudinal data remain limited (Table 2).

| Drug class | Common agents (Peds) | Mechanism of injury | Typical presentation | Notes |

| NRTIs | 3TC, ABC, TDF, TAF (older: d4T, ddI) | Mitochondrial toxicity, hypersensitivity (ABC) | Steatosis, lactic acidosis, hepatitis | d4T/ddI largely phased out; ABC requires HLA-B*57:01 testing |

| NNRTIs | Nevirapine, Efavirenz | Immune-mediated hypersensitivity | Acute hepatitis, rash-hepatitis syndrome | Nevirapine risk highest in young children and females |

| PIs | LPV/r, Darunavir | Metabolic derangements, direct hepatotoxicity | Dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, transaminase elevations | Contributes to NAFLD risk in adolescents |

| INSTIs | Dolutegravir, Bictegravir | Weight gain, metabolic changes | Subclinical steatosis, mild ALT elevations | Generally safe; long-term pediatric outcomes unknown |

Table 2: Antiretroviral class–specific hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents.

Results and Discussion

Comorbidities and contextual risks

Viral hepatitis co-infection: Children with HIV frequently acquire HBV or HCV via vertical transmission or early exposure. Co-infection accelerates liver injury and increases ART-related hepatotoxicity [42]. In such cases, ART regimens must include agents active against HBV (TDF or TAF plus 3TC or FTC) to prevent reactivation or flare. Monitoring should be more intensive, with baseline and periodic HBV DNA or HCV RNA testing where feasible.

Tuberculosis co-treatment: HIV–TB co-infection is common in children, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Standard TB therapy (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide) carries intrinsic hepatotoxic risk, which may be additive with ART. Pediatric studies show DILI incidence of 5–15% during concomitant ART and TB treatment, with risk factors including malnutrition, female sex, and elevated baseline liver enzymes [43].

Malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency: Protein-energy malnutrition impairs hepatic glutathione-mediated detoxification, increasing vulnerability to oxidative stress and hepatocellular injury. In resource-limited settings, this synergizes with ART toxicity. Conversely, in high-income countries, pediatric HIV survivors face rising obesity rates, leading to NAFLD risk [44,45].

Genetic susceptibility: Pharmacogenomic studies highlight genetic predispositions to hepatotoxicity. NAT2 polymorphisms affect isoniazid metabolism, increasing TB-related hepatotoxicity,while CYP2B6 variants alter NNRTI metabolism [46]. Screening for HLA-B*57:01 before abacavir initiation is recommended where feasible, though its predictive value in pediatrics is understudied.

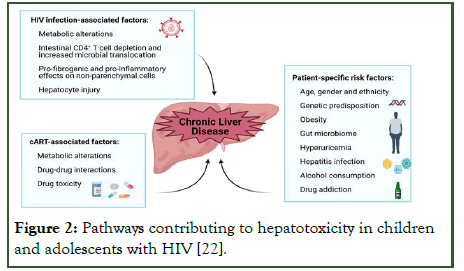

Emerging NAFLD and NASH: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is now recognized as a leading cause of chronic liver disease in adolescents with HIV, particularly those exposed to long-term ART and with obesity or metabolic syndrome. Studies show NAFLD prevalence of 15–30% in perinatally infected adolescents in high-income settings, though under-diagnosed in low-income regions due to lack of imaging and biomarkers (Figure 2) [47].

Figure 2: Pathways contributing to hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents with HIV [22].

Clinical spectrum and monitoring

Spectrum of hepatotoxicity: The clinical manifestations range from asymptomatic transaminase elevation to fulminant hepatic failure. Most children experience mild, transient enzyme elevations. Severe outcomes such as lactic acidosis with older NRTIs or immune-mediated hepatitis with Nevirapine are less common but clinically significant [48,49]. Chronic injury, including fibrosis and NAFLD, is increasingly observed in adolescents transitioning to adult care [47].

Grading and definitions: Pediatric hepatotoxicity is graded using the Division of AIDS (DAIDS) toxicity tables: Grade 1 (mild) ALT/AST elevation to Grade 4 (life-threatening) [50]. Causality is often assessed using the RUCAM (Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method), though pediatric-specific validation is limited [51].

Monitoring recommendations: Guidelines recommend baseline liver function testing before ART initiation or modification, with repeat testing at 2–4 weeks, 3 months, and every 6–12 months thereafter. In higher-risk children (HBV/HCV co-infection, TB co-treatment, use of nevirapine or PIs), more frequent monitoring is advised [52]. Non-invasive fibrosis assessment tools such as APRI and FIB-4 are under study but not validated for routine pediatric use (Table 3).

| Time point | Recommended tests | High-risk populations (e.g., HBV/HCV, TB therapy, NNRTIs) |

| Baseline | ALT, AST, bilirubin, HBV/HCV serology, nutritional assessment | Add HBV DNA or HCV RNA if feasible |

| 2–4 weeks after ART initiation | ALT, AST | Monitor closely if on Nevirapine or TB co-treatment |

| 3 months | ALT, AST, bilirubin | Add lipids if on PI/INSTI |

| 6–12 months | ALT, AST | More frequent (every 3 months) if co-infected or on high-risk regimens |

| Annually | ALT, AST, bilirubin, metabolic panel | Add FibroScan/APRI if available |

Table 3: Monitoring schedule for children and adolescents on ART.

Management strategies

General principles: Management depends on severity, causality, and clinical status. Mild, asymptomatic enzyme elevations may only require continued monitoring. Moderate to severe hepatotoxicity may necessitate dose interruption, regimen switch, or hospitalization in fulminant cases [53].

Grade-based approach:

• Grade 1–2 (Mild/moderate): Continue ART with close monitoring.

• Grade 3 (Severe): Interrupt suspect drug(s); investigate for alternative etiologies (viral hepatitis, TB drugs).

• Grade 4 (Life-threatening): Discontinue all hepatotoxic agents; provide supportive care; restart with safer regimen once stable.

Switching strategies: If Nevirapine-induced hepatitis occurs, the drug should be permanently discontinued and replaced with an INSTI or PI [54]. In cases of Abacavir hypersensitivity, rechallenge is contraindicated, and alternative NRTIs must be selected. Children with HBV co-infection should always remain on HBV-active ART, even if hepatotoxicity occurs, to prevent viral reactivation [55].

Adjunctive measures: Optimizing nutrition, treating viral hepatitis, and managing metabolic syndrome are essential components of hepatotoxicity management. Vaccination against HBV and avoidance of hepatotoxic concomitant drugs when possible should be emphasized [56]. In adolescents, counseling on alcohol and substance use is important.

Long-term outcomes

Recovery and reversibility: Most children with ART-related hepatotoxicity experience full biochemical recovery after drug withdrawal or substitution. However, subclinical damage may persist, particularly in those with repeated episodes of DrugInduced Liver Injury (DILI) or concurrent risk factors.

Fibrosis and cirrhosis: Persistent hepatic inflammation may progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis, particularly in children with viral hepatitis co-infection or metabolic risk factors. Elastography studies in perinatally infected adolescents report early signs of fibrosis in 10–15% despite viral suppression [57].

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Risk: While pediatric HCC remains rare, chronic HBV co-infection combined with ARTinduced hepatotoxicity may increase lifetime risk [58]. A few case reports document HCC in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents with longstanding HBV co-infection. Surveillance strategies should be considered in high-risk populations [59].

Psychosocial and quality of life outcomes: Adolescents experiencing recurrent hepatotoxicity may require regimen switches that limit treatment options, creating anxiety about drug failure [60]. Chronic illness burden, frequent monitoring, and dietary restrictions may further impact adherence and quality of life (Table 4).

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Risk: While pediatric HCC

| Outcome | Frequency/Prevalence | Risk Factors | Notes |

| Biochemical recovery | 70–80% after drug discontinuation | Mild/moderate DILI, early detection | Majority recover fully |

| Persistent ALT elevation | 20–30% in longitudinal studies | Recurrent DILI, HBV/HCV, obesity | May progress to fibrosis |

| Fibrosis | 10–15% of perinatally infected adolescents | HBV/HCV, PIs, obesity, malnutrition | Underdiagnosed in LMICs |

| Cirrhosis | Rare but reported in teens | Chronic HBV/HCV, repeated hepatotoxicity | Requires lifelong surveillance |

| HCC | Rare case reports | HIV/HBV co-infection, chronic liver disease | Lifelong risk persists |

Table 4: Long-term outcomes of ART-related hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents.

Future perspectives

Safer ART regimens: The shift toward integrase inhibitors (Dolutegravir, Bictegravir) in pediatric populations is promising, with reduced hepatotoxicity compared to NNRTIs and PIs [61]. Ongoing surveillance for metabolic consequences and NAFLD is essential. Development of long-acting injectable ART formulations may reduce cumulative hepatic exposure but requires pediatric safety studies.

Precision medicine approaches: Pharmacogenomic testing (e.g., HLA-B*57:01, CYP2B6 polymorphisms) should be integrated into pediatric HIV programs where feasible. Tailoring ART based on genetic risk may prevent idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity and optimize drug safety [62].

Improved monitoring tools: Non-invasive methods such as transient elastography, MRI-based fat quantification, and serum fibrosis biomarkers need validation in children [63]. These tools could replace invasive biopsies for longitudinal monitoring.

Research gaps:

•Lack of long-term prospective cohorts of perinatally infected children to assess chronic liver outcomes.

•Limited data from Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), where hepatotoxicity burden is likely higher.

•Under-exploration of sex and puberty-related differences in susceptibility.

•Few interventional trials evaluating adjunctive therapies (antioxidants, hepatoprotective agents) in pediatric populations.

Conclusion

ART has transformed pediatric HIV into a chronic, manageable condition, but hepatotoxicity remains a clinically significant complication. The risk is shaped by drug class, host factors, comorbidities, and environmental context. While most children recover fully, a subset progress to chronic liver disease, fibrosis, or cirrhosis, especially when additional risk factors such as HBV/HCV, TB treatment, or obesity are present.

Future strategies must focus on safer regimens, pharmacogenomic screening, improved monitoring, and targeted interventions to mitigate hepatotoxicity. Strengthening pediatric-specific research and ensuring access to diagnostic tools in LMICs will be critical to safeguard long-term liver health in children and adolescents living with HIV

References

- UNAIDS. Global HIV and AIDS statistics 2024 fact sheet. Geneva: UNAIDS. 2024.

- Global statistics. The global HIV and AIDS epidemic. 2025.

- Abrams EJ, Strasser S. 90-90-90 Charting a steady course to end the pediatric HIV epidemic. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20296.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feeney ER, Mallon PW. HIV and HAART-associated dyslipidemia. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2011;5:49–63.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Den Brinker M, Wit FW, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, Jurriaans S, Weel J, van Leeuwen R, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus co-infection and the risk for hepatotoxicity of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2000;14(18):2895–2902.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scarsi KK, Darin KM, Rawizza HE, Meloni ST, Kline ER, Abrams EJ, et al. Liver function tests and hepatotoxicity among HIV-infected children on ART in Nigeria. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(2):e45–e50.

- Galli L, Chiappini E, Gabiano C, Giaquinto C, Tovo PA, de Martino M. Liver toxicity in HIV-infected children and adolescents receiving ART. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(4):448–456.

- Bitnun A, Samson LM, Kakkar F, Brophy J, Kakkar F, Lee T, et al. Metabolic complications and hepatotoxicity in perinatally HIV-infected youth: A review. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2019;14(1):34–42.

- Low A, Gavriilidis G, Larke N. Incidence of severe liver toxicity in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(1):e22–e31.

- Rivera DM, Steele RW, editors. Pediatric HIV infection treatment and management: Approach considerations, overview of antiretroviral therapy. Medscape; 2025.

- World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring. 2021.

- Pecani M, Andreozzi P, Cangemi R, Corica B, Miglionico M, Romiti GF, et al. Metabolic syndrome and liver disease: Re-appraisal through the paradigm shift from NAFLD to MASLD. J Clin Med. 2025;14(8):2750.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Núñez M. Clinical syndromes and consequences of antiretroviral-related hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):1143–1155.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dieterich DT, Robinson PA, Love J, Stern JO. Drug-induced liver injury associated with nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:S80–S89.

- Pérez-Matute P, Pérez-Martínez L, Blanco JR, Oteo JA. Role of mitochondria in HIV infection and associated metabolic disorders: Focus on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and lipodystrophy syndrome. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:493413.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Kim YJ, Kim SI, Kim YR, Woo JH. Abacavir-induced hypersensitivity reaction presenting with severe hepatitis and renal failure. Infect Chemother. 2012;44(5):399–402.

- Drugs.com. Nevirapine: Package insert/prescribing information. 2025.

- Bischoff J, Gu W, Schwarze-Zander C, Boesecke C, Wasmuth JC, van Bremen K, et al. Stratifying the risk of NAFLD in patients with HIV under cart. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101116.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lake JE, Overton T, Naggie S, Sulkowski M, Loomba R, Kleiner DE, et al. Expert panel review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in persons with HIV. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):256–268.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fry SH-L, Barnabas SL, Cotton MF. Tuberculosis and HIV—an update on the “cursed duet” in children. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:159.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strassburg CP, Strassburg A, Kneip S, Barut A, Tukey RH, Rodeck B, et al. Developmental aspects of human hepatic drug glucuronidation in young children and adults. Gut. 2002;50(2):259–265.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benedicto AM, Fuster-Martínez I, Tosca J, Esplugues JV, Blas-García A, Apostolova N. NNRTI and liver damage: Evidence of their association and mechanisms involved. Cells. 2021;10(7):1687.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Ziemba L, Tierney C, Reding C, Bone F, Bradford S, et al. Micronutrients and nutritional status among children living with HIV with and without severe acute malnutrition: IMPAACT P1092. BMC Nutr. 2023;9(1):121.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blázquez D. Lipid and glucose alterations in perinatally acquired HIV-infected adolescents and young adults receiving antiretroviral therapy. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:85.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wells RG. Hepatic fibrosis in children and adults. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2017;9(4):99–101.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Recovery Research Institute. Uncovering the ingredients of successful adolescent recovery. Boston: Massachusetts General Hospital. 2020.

- Gil AC-M. Hepatotoxicity in HIV-infected children and adolescents on antiretroviral therapy: Elevation of serum liver enzymes and possible mechanisms. J Pediatr. 2007.

- Rivera CG, Otto AO, Zeuli JD, Temesgen Z. Hepatotoxicity of contemporary antiretroviral drugs. Cells. 2021;16(6):279-285.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rose PC, Nel ED, Cotton MF, Pitcher RD, Otwombe K, Browne SH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for hepatic steatosis in children with perinatal HIV on early antiretroviral therapy. Front Pediatr. 2022:10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benedicto AM, Fuster-Martínez I, Tosca J, Esplugues JV, Blas-García A, Apostolova N, et al. NNRTI and liver damage: Evidence of their association. Cells. 2021;10(7):1687.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wallner JJ, Beck IA, Panpradist N, Ruth PS, Valenzuela-Ponce H, Soto-Nava M, et al. Rapid near point-of-care assay for HLA-B*57:01 genotype associated with severe hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;37(12):930–935.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mulu W, Gidey B, Chernet A, Alem G, Abera B. Hepatotoxicity and associated risk factors in HIV-infected patients on ART. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;23(3):217-226.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Margolis AM, Heverling H, Pham PA, Stolbach A. A review of the toxicity of HIV medications. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10(1):26–39.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chu KM, Boulle AM, Ford N, Goemaere E, Asselman V, van Cutsem G. Nevirapine-associated early hepatotoxicity: incidence, risk factors, and associated mortality in a primary care ART programme in South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9183.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brück S, Witte S, Brust J, Schuster D, Mosthaf F, Procaccianti M, et al. Hepatotoxicity in patients prescribed efavirenz or nevirapine. Eur J Med Res. 2008;13(7):343–348.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schuval SJ. Pharmacotherapy of pediatric and adolescent HIV infection. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5(3):469–484.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dejkhamron P, Unachak K, Aurpibul L, Sirisanthana V. Insulin resistance and lipid profiles in HIV-infected Thai children receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based HAART. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27:403–412.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wikipedia contributors. Darunavir. Wikipedia. 2025.

- Chandasana H, Thapar M, Hayes S, Baker M, Gibb DM, Turkova A, et al. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of dolutegravir to optimize pediatric dosing in HIV-1–infected infants, children, and adolescents (IMPAACT P1093, ODYSSEY teams). Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023;62(10):1445–1459.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spector SA, Brummel SS, Chang A. Long-term safety and efficacy of dolutegravir in treatment-experienced adolescents with HIV infection: IMPAACT P1093. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2024;95(3):297–303.

- Jemal M. A review of dolutegravir-associated weight gain and secondary metabolic comorbidities. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rubino C, Stinco M, Indolfi G. Hepatitis co-infection in paediatric HIV: Progressing treatment and prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2024;19(6):338–347.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manokaran V, Kaur B. Incidence and predictors of drug-induced liver injury in pediatric tuberculosis patients under anti-tubercular therapy: A prospective observational study. Cureus. 2025;17(6):e85661.

- Becker K, Leichsenring M, Gana L, Bremer HJ, Schirmer RH. Glutathione and antioxidant systems in protein-energy malnutrition: results of a study in Nigeria. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18(2):257–263.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Accacha S. From childhood obesity to metabolic dysfunction: A growing concern. Metabolites. 2025;15(5):287.

- Mahajan R, Tyagi AK. Pharmacogenomic insights into tuberculosis treatment: NAT2 variants linked to hepatotoxicity risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Genom Data. 2024;25(1):103.

- Carrasco I, Olveira A, Lancharro Á, Escosa L, Mellado MJ, Busca C, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using noninvasive techniques among children and youth living with HIV. AIDS. 2022;36(6):805–814.

- Ndagijimana M, Walker AS, Musiime V, Kityo C, Kekitiinwa A, Ssali F, et al. Hepatotoxicity and antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children: Incidence and risk factors in the ARROW trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022;89(2):172–181.

- Núñez M. Hepatotoxicity of antiretrovirals: Incidence, mechanisms and management. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S132–S139.

- Division of AIDS (DAIDS). Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events. 2017.

- Danan G, Teschke R. RUCAM in drug and herb-induced liver injury: the update. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(1):14.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living with HIV. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection. 2023.

- Grigorian A, O’Brien CB. Hepatotoxicity secondary to chemotherapy. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2(2):95–102.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Nevirapine. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012.

- Healy SA, Gupta S, Melvin AJ. HIV/HBV coinfection in children and antiviral therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11(3):251–263.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta A, Vail RM, Shah SS, Fine SM, McGowan JP, Merrick ST, et al. Prevention and management of hepatitis B virus infection in adults with HIV. 2025.

- Pokorska-Å?piewak M, Dobrzeniecka A, LipiÅ?ska M, Tomasik A, Aniszewska M, MarczyÅ?ska M. Liver fibrosis evaluated with transient elastography in children with chronic HCV infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(2):103–108.

- Paganelli M, Stephenne X, Sokal EM. Chronic hepatitis B in children and adolescents. J Hepatol. 2012;57(4):885–896.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seers T, Sarker D, Ross P, Heaton N, Suddle A, Lyall H, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in perinatally acquired HIV and HBV coinfection: A case report. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(12):1156–1158.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Francis P, Navarro VJ. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. 2025.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamphuis AEM, Bamford A, Tagarro A, Cressey TR, Bekker A, Amuge P, et al. Optimising paediatric HIV treatment: recent developments and future directions. Paediatr Drugs. 2024;26(6):631–648.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pillaye JN, Marakalala MJ, Khumalo N, Spearman W, Ndlovu H. Mechanistic insights into antiretroviral drug-induced liver injury. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8(4):e00598.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yodoshi T. Exploring non-invasive diagnostics and non-imaging approaches for pediatric metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30(47):5070–5075.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Akter F, Jyoti HJ, Hossain S, Afroz S, Akter E, Aurnab SR, et al. (2025) Pediatric and Adolescent Considerations in Antiretroviral-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Mechanisms, Risks, Monitoring and Management. Bio Med. 17:781.

Copyright: © 2025 Akter F, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.