Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- CiteFactor

- Cosmos IF

- Scimago

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Electronic Journals Library

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Directory of Abstract Indexing for Journals

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Proquest Summons

- Scholarsteer

- ROAD

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

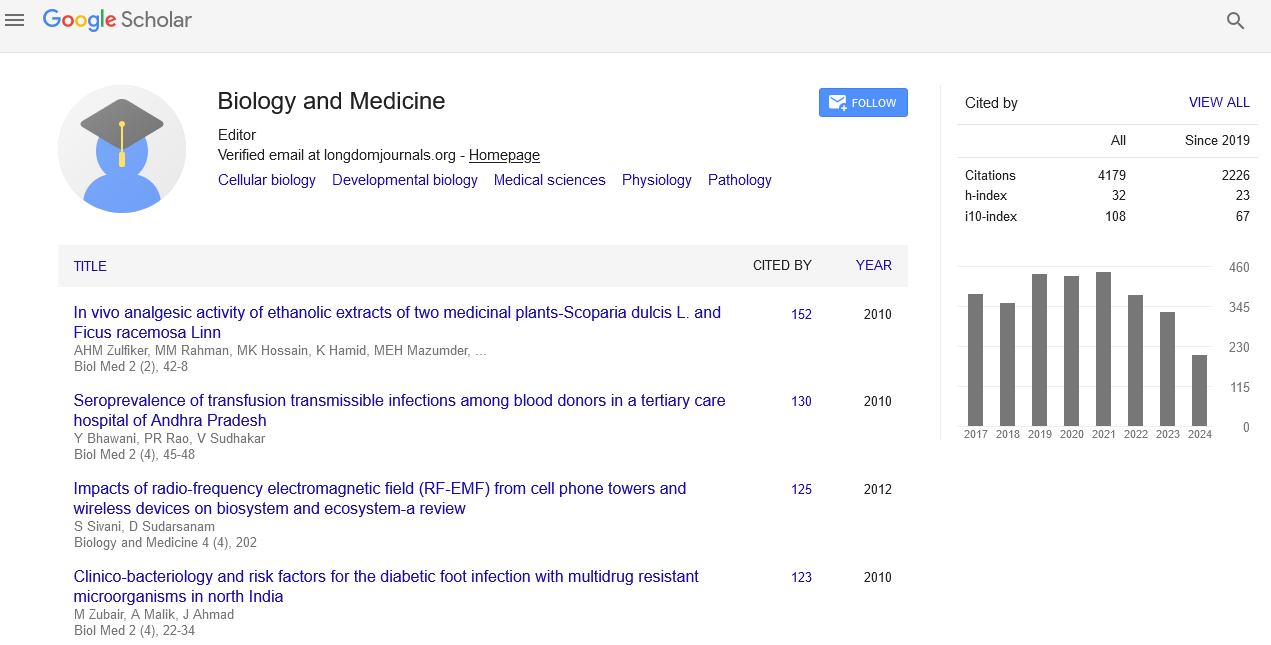

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Perspective - (2025) Volume 17, Issue 7

Epigenetics and Human Disease: Unlocking the Molecular Code Beyond DNA

Sophia Martinez*Received: 30-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. BLM-25-30086; Editor assigned: 02-Jul-2025, Pre QC No. BLM-25-30086 (PQ); Reviewed: 16-Jul-2025, QC No. BLM-25-30086; Revised: 23-Jul-2025, Manuscript No. BLM-25-30086 (R); Published: 30-Jul-2025, DOI: 10.35248/0974-8369.25.17.781

Description

The concept of epigenetics has reshaped our understanding of human biology, providing insights into how gene expression is regulated without altering the underlying DNA sequence. The term “epigenetics” refers to heritable changes in gene function that occur through modifications such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA activity. These processes act as molecular switches and dimmers, determining when and where genes are expressed. Far from being static, epigenetic patterns are dynamic, influenced by developmental cues, environmental exposures, diet, stress, and aging. As research progresses, it has become increasingly clear that epigenetic regulation plays a critical role in health and disease, offering new possibilities for diagnostics and therapeutics.

Epigenetic regulation is central to normal development. During embryogenesis, cells with identical genomes differentiate into diverse cell types through distinct epigenetic programming. DNA methylation patterns guide lineage specification, ensuring that genes unnecessary for a given cell type are silenced, while histone modifications allow fine-tuned gene activation. Disruption of these processes can result in developmental abnormalities, emphasizing their importance in orchestrating complex biological systems.

One of the most studied epigenetic mechanisms is DNA methylation, involving the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, particularly at CpG islands in gene promoter regions. Methylation typically silences gene expression by preventing transcription factor binding or recruiting proteins that compact chromatin structure. Aberrant DNA methylation has been observed in numerous diseases, most notably cancer, where hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes or hypomethylation leading to genomic instability contributes to tumorigenesis.

Histone modifications provide another layer of epigenetic control. Histones, the proteins around which DNA is wrapped, can undergo chemical modifications such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. These modifications alter chromatin accessibility, either promoting transcriptional activation or repression. For instance, histone acetylation by Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) generally correlates with gene activation, while deacetylation by histone deacetylases (HDACs) leads to gene repression. Dysregulation of histone-modifying enzymes has been implicated in a wide range of diseases, including neurodevelopmental disorders and cancers.

Non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), add further complexity to the epigenetic landscape. These molecules regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by targeting messenger RNAs for degradation or translational repression. In addition, some lncRNAs act as scaffolds for chromatin-modifying complexes, guiding them to specific genomic loci. Alterations in non-coding RNA expression profiles have been linked to cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and psychiatric conditions, highlighting their significance as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Epigenetics provides a framework for understanding how environmental factors influence health and disease. For example, nutritional status during pregnancy can shape offspring epigenomes, with lasting effects on metabolic health. Similarly, exposure to toxins, air pollution, or psychosocial stress has been shown to induce epigenetic changes associated with increased disease susceptibility.

In cancer biology, epigenetics has been transformative. Traditional views focused on genetic mutations driving malignancy, but it is now clear that epigenetic alterations are equally critical. Cancer cells often exhibit global hypomethylation alongside localized hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes. Histone-modifying enzymes such as EZH2, a histone methyltransferase, are frequently overexpressed, leading to silencing of key regulatory pathways. These insights have spurred the development of epigenetic therapies, including DNMT inhibitors (e.g., azacitidine and decitabine) and HDAC inhibitors (e.g., vorinostat and romidepsin), which have shown clinical efficacy in hematological malignancies.

Neurobiology is another field profoundly influenced by epigenetics. Learning and memory are dependent on activitydriven epigenetic modifications that regulate synaptic plasticity. Aberrant epigenetic regulation has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s, as well as psychiatric disorders like depression and schizophrenia. The reversibility of epigenetic marks raises hopes for therapeutic interventions targeting these pathways.

Aging represents a cumulative process of epigenetic drift, where DNA methylation patterns gradually change over time. “Epigenetic clocks,” based on DNA methylation profiles, have emerged as accurate predictors of biological age, surpassing chronological age in reflecting health status. These biomarkers are being explored for their potential in personalized medicine, guiding lifestyle interventions and therapeutic strategies to promote healthy aging.

The future of epigenetics in medicine is poised for rapid growth. Advances in single-cell epigenomics allow unprecedented Bio resolution in understanding cellular heterogeneity within tissues and tumors. CRISPR-based epigenome editing tools enable precise manipulation of epigenetic marks without altering DNA sequences, opening new avenues for targeted therapies. Integration of epigenomic data with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets will provide holistic insights into disease mechanisms.

In conclusion, epigenetics represents a molecular layer of regulation bridging the static genome and the dynamic environment. It is a field that explains how lifestyle, environment, and genetics converge to shape health outcomes. From cancer and neurological diseases to aging and metabolic disorders, epigenetic mechanisms are central to pathophysiology and hold great promise for precision medicine. By continuing to unravel this complex molecular code, biology and medicine can move closer to achieving therapies that are not only effective but also tailored to individual epigenetic landscapes.

Citation: Martinez S (2025). Epigenetics and Human Disease: Unlocking the Molecular Code Beyond DNA. Bio Med. 17:781.

Copyright: © 2025 Martinez S. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.