Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Proquest Summons

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Review - (2025) Volume 16, Issue 5

Effectiveness of Pathogen Reduction Techniques in Fresh Blood Products for Enhancing Community Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Jingchun Gao*Received: 15-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. JBDT-25-30318; Editor assigned: 17-Nov-2025, Pre QC No. JBDT-25-30318 (PQ); Reviewed: 01-Dec-2025, QC No. JBDT-25-30318; Revised: 08-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JBDT-25-30318 (R); Published: 15-Dec-2025, DOI: 10.4172/2155-9864.25.16.629

Abstract

Transfusions of fresh blood products are a vital part of modern medical care, but they still carry the risk of transmitting infections. To address this, Pathogen Reduction Technologies (PRTs) have been developed as an added safety layer by deactivating potential infectious agents in blood components. This systematic review and meta-analysis, conducted in line with PRISMA guidelines, examined how effectively these technologies improve transfusion safety and public health. A thorough search of PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar identified peer- reviewed, full-text studies published in English over the last decade. Eligible studies compared pathogen-reduced blood products with standard ones. Data on Transfusion-Transmitted Infections (TTIs) and Transfusion-Related Adverse Events (TRAEs) were extracted and analysed using a random-effects model in RevMan 5.4, with pooled Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs). Six studies were included, covering more than five million platelet transfusions. All focused on the INTERCEPT® system, which uses amotosalen and UVA light. The meta- analysis found a significantly lower risk of TTIs in PRT-treated platelets (OR 14.42; 95% CI 3.57-58.18; P=0.0002; I²=29%). While the overall rate of TRAEs was not significantly different (OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.80-1.60; P=0.49), subgroup analysis showed notable reductions in Allergic Reactions (ATRs), Severe Adverse Reactions (SARs), Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO), and Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI). These findings suggest that PRTs-particularly the INTERCEPT® system-effectively reduce transfusion-related infection risks without compromising overall safety.

Keywords

PRT treated platelet concentrates; Transfusion-transmitted infections; Intercept system; TACO; TRALI; SARs; TRAEs.

Introduction

As the global population continues to rise, the utilisation of fresh blood product transfusion, recognised as a vital life-saving modality, has substantially expanded in demand [1]. However, the widespread application of blood products has also been accompanied by an increased risk of TTIs, particularly among patients requiring repeated transfusions or massive transfusion support [2,3]. Blood transfusion may serve as a vehicle for the transmission of diverse infectious agents, ranging from classical pathogens such as syphilis, hepatitis B and C viruses, and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), to emerging infections including dengue, malaria, and zoonotic diseases such as babesiosis [4-6]. Over the past decade, effective screening strategies such as nucleic acid testing, serological antibody screening, and donor evaluation with deferral procedures have been developed, substantially reducing the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections from well-recognised pathogens, including hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and other infectious agents [7-9].

Limits of current screening

Despite the adoption of advanced and rigorous screening measures, transfusion safety cannot be fully guaranteed. Window-period infections pose a particular challenge, as available tests may not identify infected donors. Window-period infections and undetectable or emerging pathogens may still escape detection, particularly when donor samples are pooled [10,11]. Parasitic and bacterial agents also contribute to residual transfusion risk, as current serological assays cannot detect all species [12]. In platelets, storage at room temperature maintains function but promotes bacterial growth, posing an additional threat to immunocompromised recipients [13]. Even with bacterial screening systems such as BacT/ALERT©, certain pathogens may evade detection, and false-positive results can lead to unnecessary product wastage [14].

Globalisation and the increasing frequency of international travel have heightened the risk of emerging transfusion-transmitted pathogens. Outbreaks such as Zika or dengue in endemic regions often necessitate delaying transfusions, recalling potentially affected units, or importing blood from unaffected areas. Although these temporary safeguards are effective, they disrupt blood availability and substantially increase healthcare costs [15].

Pathogen reduction technologies

Pathogen Reduction Technology (PRT) refers to a proactive strategy in transfusion medicine that employs physical or chemical methods to treat blood products, thereby inactivating potential pathogens and reducing the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections [16-18]. The Mirasol® system uses riboflavin (vitamin B2) activated by UV light; as riboflavin residues are non-toxic, removal after illumination is unnecessary, preserving platelet yield and post-transfusion efficacy across plasma, platelets, red cells, and whole blood [19-21].

In the INTERCEPT® system, a psoralen derivative called amotosalen is activated with ultraviolet A light (320-400 nm) to form covalent crosslinks with nucleic acids, thereby preventing microbial replication and achieving pathogen inactivation. The system is applied to plasma and platelets; however, amotosalen must be removed using a dedicated adsorption device, which leads to 10% platelet loss [22,23]. The THERAFLEX® system currently employs two pathogen inactivation approaches: The Methylene Blue (MB) plasma system and the UV-C technology. The MB plasma system combines filtration with Methylene Blue (MB) and illumination at 630 nm visible light to inactivate pathogens in single plasma units. In contrast, the UV-C technology requires only the agitation of platelet concentrates in an additive solution, which enhances the penetration of UVC light without the requirement for photosensitising chemicals [24]. This substantially reduces the toxicological burden associated with the procedure [25]. The reduction in blood product processing time helps to mitigate the logistical time constraints associated with patient allocation and transportation [26].

Although these different PRTs are effective in addressing pathogens in fresh blood products, the additional processing costs have limited their implementation mainly to high-income countries and a few middle-income settings [15]. A blood establishment considers the cost-effectiveness of testing and pathogenâ?ÂÂreduction strategies [27]. At present, no more affordable PRT technologies have been developed that would allow widespread use in low-resource regions. At the same time, concerns remain regarding the potential alteration or degradation of blood products by PRT. Currently, INTERCEPT® has been approved for the treatment of platelets and plasma in 22 and 13 countries, respectively, Mirasol® has been approved for platelets and plasma in 18 and 11 countries, respectively and THERAFLEX® has been approved for fresh frozen plasma in 15 countries [28,29]. PRTs have also been reported to present certain drawbacks, including an increased risk of bleeding, lower post-transfusion platelet counts, decreased transfusion efficacy, and the possibility of rare pathogen escape [30,31]. This raises the important question of whether the application of PRTs truly enhances community-level health. To date, most studies on PRT-mediated pathogen inactivation have been conducted in vitro rather than in clinical settings, resulting in a lack of substantive clinical evidence.

Although PRTs are increasingly applied to fresh blood products, their overall impact on community-level transfusion safety remains uncertain. Guided by the Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome (PICO) approach, the central research question of this review is: In individuals receiving transfusions of fresh blood products (population), does the application of pathogen reduction technologies (intervention), relative to standard untreated products (comparator), reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections and thereby improve community-level public health (outcome)?

Methods

Study design

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [32].

Selection criteria

Types of studies: The included studies were observational haemovigilance reports, retrospective and prospective cohort analyses, and clinical trials. All studies compared transfusion-related safety outcomes between pathogen-reduced and conventional blood products. Only full-text, peer-reviewed articles published in English within the last 10 years were included. Conference abstracts, reviews, case series with <5 patients, and inaccessible manuscripts were excluded.

Types of participants: Eligible participants were patients who received blood transfusions in different clinical settings. There were no limits on age, sex, or underlying condition. The settings included haematology-oncology, cardiac surgery, intensive care, paediatric and neonatal units, and general medical and surgical wards. Patients in whom adverse events were caused by non-transfusion-related diseases or comorbidities, rather than the transfusion, were excluded.

Types of interventions and comparators: The interventions were transfusions of fresh blood products treated with licensed pathogen- reduction systems. These included INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/ Ultraviolet A (UVA)), Mirasol® (riboflavin/UV), and THERAFLEX® (methylene blue/visible light or Ultraviolet C (UVC)). Only studies directly compared pathogenâ?reduced products with similar non- pathogen-reduced blood products were included. Reports without a comparison group or using other processing methods were excluded.

Types of outcome measures: The included studies were required to compare TTIs and TRAEs between pathogen-reduced and conventional blood products. Studies that did not report reliable, consistent, or extractable data on these outcomes were excluded.

Search methods for identification of studies

A comprehensive search was performed in Scopus, Google Scholar, and PubMed to identify studies published within the past 10 years. There were no limits on language, date, or publication status. The search used keywords alone or combined with Boolean operators (‘AND’, ‘OR’, ‘NOT’). Wildcard symbols were also added to widen the results. Keywords focused on four domains: (1) blood products and components (platelet concentrates, fresh frozen plasma, red blood cells); (2) pathogen reduction technologies (pathogen inactivation, pathogen-reduced blood, amotosalen/UVA, riboflavin/UV light); (3) infection and transfusion risk (transfusion-transmitted infections, emerging infectious diseases, bloodborne pathogens); and (4) public health perspective (community safety, risk mitigation, cost-effectiveness of blood safety). Examples of search combinations included: “pathogen inactivation” AND “platelet concentrates”, “transfusion-transmitted infections” AND “community risk”, “pathogen reduction” AND “public health benefit”, and (“platelet concentrates” OR “fresh frozen plasma” OR “red blood cells”) AND (“pathogen reduction” OR “pathogen inactivation”).

Data extraction and management

One reviewer screened all search results step by step based on the set eligibility criteria. Titles and abstracts were checked first. If eligibility was unclear, the full text was reviewed. For each included study, data were extracted on key study characteristics (author, year of publication, country, setting, and study design), population details (sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, baseline demographics), and intervention features (type of blood product, pathogen- reduction method, comparison group, transfusion period, and storage conditions). Outcome measures were systematically recorded, including TTIs, TRAEs, and any additional safety endpoints reported.

Assessment of methodological quality

Each study's quality and possible risk of bias were assessed using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [33].

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes were the rates of TTIs and TRAEs in pathogen- reduced (PRT-treated) blood products compared with non-treated blood products. Data were analysed using Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.4, Cochrane collaboration). For binary outcomes, pooled ORs with 95% CIs were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method under a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed with the Chi-square (Chi²) test and quantified using the Higgins I² statistic. Values of I² above 50% were considered to show substantial heterogeneity. A two- sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results were presented as forest plots, supported by summary figures showing the risk of bias.

Results

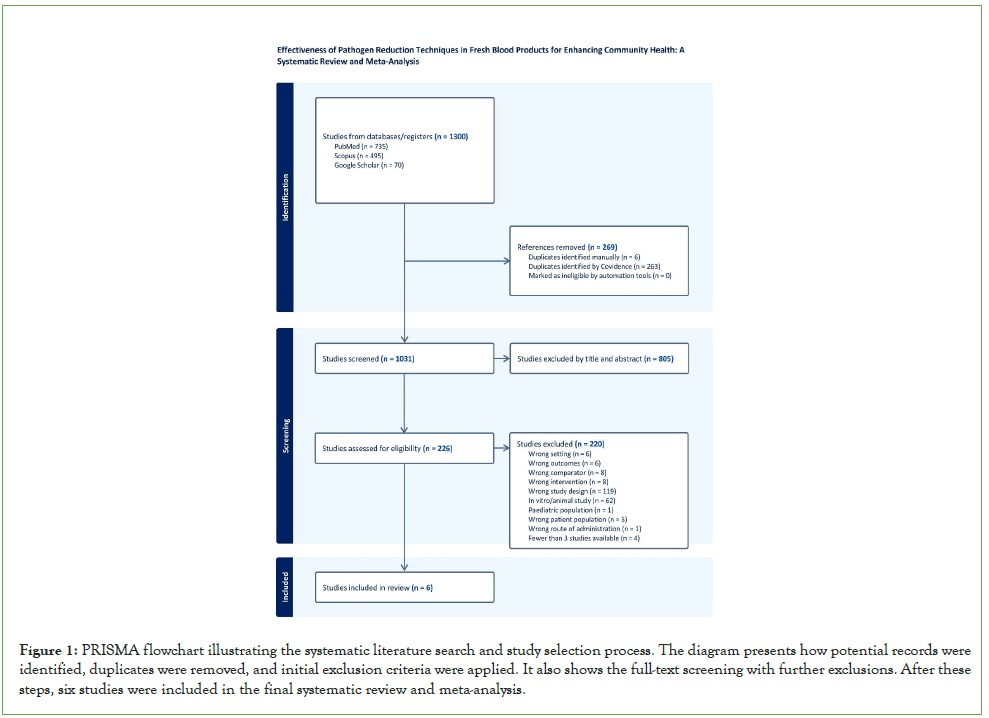

Selection of studies

The search identified 1300 potentially relevant articles (PubMed, n=735; Scopus, n=495; Google Scholar, n=70). After removing 269 duplicates (manually identified, n=6; covidence, n=263), 1031 records were screened by title and abstract. Out of these, 805 were excluded as not meeting the eligibility criteria. The remaining 226 full-text articles were reviewed for eligibility. After full-text assessment, 220 studies were excluded for inappropriate study design (n=119), in vitro or animal research (n=62), and other reasons. Ultimately, six studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review and meta- analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart illustrating the systematic literature search and study selection process. The diagram presents how potential records wereidentified, duplicates were removed, and initial exclusion criteria were applied. It also shows the full-text screening with further exclusions. After these steps, six studies were included in the final systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the six included studies are shown in (Table 1). All studies investigated using the INTERCEPT® pathogen reduction system (amotosalen/UVA) in platelets. The study periods ranged from 2007 to 2022. Five studies used a retrospective design, and one used a prospective approach [34-39]. The studies were conducted in Austria, France, and the USA, with total platelet unit sample sizes varying widely, from fewer than 1,000 units to over 3 million units [36,38].

| Primary author | Country | Study design | Study period | PRT method | Total sample size (platelet units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amato, et al. 2017 [34] | Austria | Retrospective | Apr 2011-Dec 2012 Apr 2013-Dec 2014 |

INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/UVA) |

16316 |

| Andreu, et al. 2025 [35] | France | Retrospective | Jan 2007-Dec 2010 Jan 2018-Dec 2021 |

INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/UVA) |

2358580 |

| Lasky, et al. 2021 [36] | USA | Retrospective | Feb 2017-Dec 2017 | INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/UVA) |

892 |

| Mowla, et al. 2021 [37] | USA | Retrospective | Jan 2010-Dec 2018 | INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/UVA) |

1474687 |

| Richard, et al. 2024 [38] | France | Retrospective | Jan 2013-Dec 2022 | INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/UVA) |

3012330 |

| Snyder, et al. 2022 [39] | USA | Prospective | Dec 2015-May 2021 | INTERCEPT® (amotosalen/UVA) |

10764 |

Table 1: Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis of TRAEs and TTIs in PRT-treated and non-PRT platelets, following PRISMA exclusion criteria.

The clinical outcomes included TTIs, TRAEs, ATRs, and SARs. Several studies reported specific adverse events, including FNHTR, TACO, and TRALI. Despite variations in study design and sample size, the overall evidence provided a comprehensive evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of PRT-treated platelets in different clinical and geographical settings.

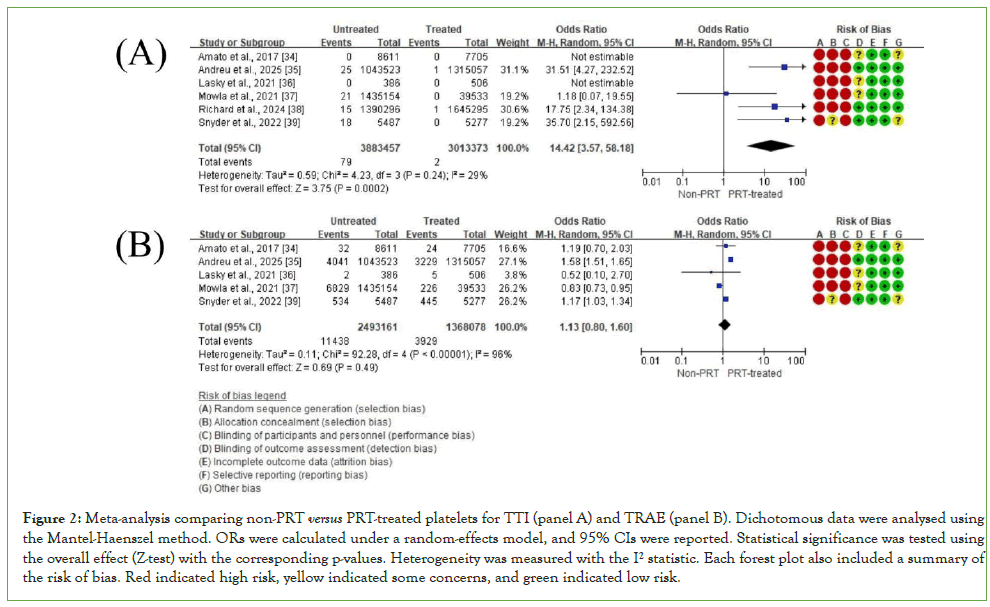

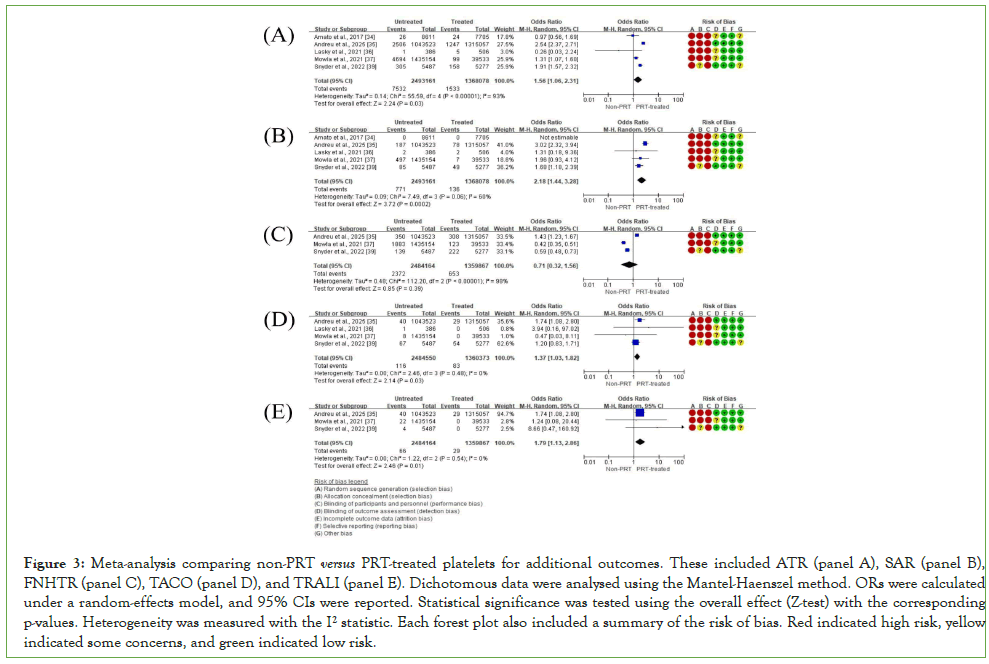

Meta-analysis

Data extracted from studies that met the meta-analysis criteria are listed in (Table 2). The results are shown as proportions (events/total) based on each study's original platelet unit data. When only percentages were available, event numbers were calculated from the total counts to allow analysis. All outcomes were binary, and no mean or standard deviation values were used. TTIs and TRAEs were presented as ORs with 95% CIs in forest plots (Figure 2, panels A-B). Additional outcomes, including ATRs, SARs, FNHTRs, TACO, and TRALI, were also presented as ORs with 95% CIs in forest plots (Figure 3, panels A-E).

| Study | Total size N | TTI | TRAE | ATR | SAR | FNHTR | TACO | TRALI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amato, et al. 2017 [34] |

16316 | PR: 0/7705 nPR: 0/8611 |

PR: 24/7705 nPR: 32/8611 |

PR: 24/7705 nPR: 26/8611 |

PR: 0/7705 nPR: 0/8611 |

- | - | - |

| Andreu, et al. 2025 [35] |

2358580 | PR: 1/1315057 nPR: 25/1043523 |

PR: 3229/1315057 nPR: 4041/1043523 |

PR: 1247/1315057 nPR: 2506/1043523 |

PR: 78/1315057 nPR: 187/1043523 |

PR: 308/1315057 nPR: 350/1043523 |

PR: 29/1315057 nPR: 40/1043523 |

PR: 12/1315057 nPR: 46/1043523 |

| Lasky, et al. 2021 [36] |

892 | PR: 0/506 nPR: 0/386 |

PR: 5/506 nPR: 2/386 |

PR: 5/506 nPR: 1/386 |

PR: 2/506 nPR: 2/386 |

- | PR: 0/506 nPR: 1/386 |

- |

| Mowla, et al. 2021 [37] |

1474687 | PR: 0/39533 nPR: 21/1435154 |

PR: 226/39533 nPR: 6829/1435154 |

PR: 99/39533 nPR: 4694/1435154 |

PR: 7/39533 nPR: 497/1435154 |

PR: 123/39533 nPR: 1883/1435154 |

PR: 0/39533 nPR: 8/1435154 |

PR: 0/39533 nPR: 22/1435154 |

| Richard, et al. 2024 [38] |

3012330 | PR: 1/1645295 nPR: 15/1390296 |

||||||

| Snyder, et al. 2022 [39] |

10764 | PR: 0/5277 nPR: 18/5487 |

PR: 445/5277 nPR: 534/5487 |

PR: 158/5277 nPR: 305/5487 |

6PR: 49/5277 nPR: 85/5487 |

PR: 222/5277 nPR: 139/5487 |

PR: 54/5277 nPR: 67/5487 |

PR: 0/5277 nPR: 4/5487 |

Table 2: Data extracted from eligible studies for the meta-analysis comparing PRT-treated versus non-PRT platelets.

Figure 2: Meta-analysis comparing non-PRT versus PRT-treated platelets for TTI (panel A) and TRAE (panel B). Dichotomous data were analysed using the Mantel-Haenszel method. ORs were calculated under a random-effects model, and 95% CIs were reported. Statistical significance was tested using the overall effect (Z-test) with the corresponding p-values. Heterogeneity was measured with the I² statistic. Each forest plot also included a summary of the risk of bias. Red indicated high risk, yellow indicated some concerns, and green indicated low risk.

Figure 3: Meta-analysis comparing non-PRT versus PRT-treated platelets for additional outcomes. These included ATR (panel A), SAR (panel B), FNHTR (panel C), TACO (panel D), and TRALI (panel E). Dichotomous data were analysed using the Mantel-Haenszel method. ORs were calculated under a random-effects model, and 95% CIs were reported. Statistical significance was tested using the overall effect (Z-test) with the corresponding p-values. Heterogeneity was measured with the I² statistic. Each forest plot also included a summary of the risk of bias. Red indicated high risk, yellow indicated some concerns, and green indicated low risk.

Assessment of study quality

The STROBE-based quality assessment of the included studies. Overall, the reporting quality was acceptable (Table 3). All studies clearly stated their aims, provided background information, and described the study design. They also outlined eligibility criteria, platelet collection and processing methods, outcome assessments, and statistical approaches. In addition, most studies mentioned how they tried to reduce bias and acknowledged their limitations. However, participant information was only partly complete in all studies, showing some demographic and clinical details. Nonetheless, the primary outcomes of this review-TRAEs and TTIs-were well defined and consistently reported. While most studies attempted to adjust for confounding, the possibility of residual bias remains due to the observational design.

| Study | Title and abstract Clear title and abstract with study design indicated |

Introduction Explains the scientific background |

Methods Detailed study methods given |

Methods Eligibility criteria for participants described |

Results Describes statistical methods |

Results Describes any efforts to address potential bias |

Discussion Gives characteristics of the study participants |

Discussion Summarises the main findings and discusses the study's limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amato, et al. 2017 [34] |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | P |

| Andreu, et al. 2025 [35] |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y |

| Lasky, et al. 2021 [36] |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y |

| Mowla, et al. 2021 [37] |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y |

| Richard, et al. 2024 [38] |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y |

| Snyder, et al. 2022 [39] |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y |

Note : Symbols: Y=Standard achieved; P=Standard partly achieved; N=Standard not achieved

Table 3: Evaluation of eligible studies according to the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) checklist.

Meta-analysis associated with Transfusion-transmitted infections

The meta-analysis showed a significantly lower risk of TTIs in patients who received PRT-treated platelets compared to those who received untreated ones (OR=14.42; 95% CI: 3.57-58.18; P=0.0002; I²=29%). The low heterogeneity strengthens confidence in this estimate. However, the wide confidence interval suggests some variability in the effect size across different studies.

Meta-analysis associated with Transfusion-related adverse events

The pooled analysis of TRAEs showed no significant overall difference between PRT-treated and non-PRT platelets (OR=1.13; 95% CI: 0.80-1.60; P=0.49), although heterogeneity across studies was high (I²=96%). However, subgroup analyses revealed that specific adverse reactions were less common with PRT-treated platelets. ATRs and SARs occurred at significantly lower rates in the PRT group (ATR: OR=1.56; 95% CI: 1.06-2.31; P=0.03; I²=93%; SAR: OR=2.18; 95% CI: 1.44- 3.28; P=0.0002; I²=60%). Similarly, the risk of TACO and TRALI was also reduced with PRT use (TACO: OR=1.37; 95% CI: 1.03-1.82; P=0.03; I²=0%; TRALI: OR=1.79; 95% CI: 1.13-2.86; P=0.01; I²=0%). In contrast, FNHTRs showed no significant difference between groups (OR=0.71; 95% CI: 0.32-1.56; P=0.39; I²=98%).

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB 1.0 tool in RevMan. The results are shown in each forest plot in Figures 2 and 3. Because all included studies were non-randomised, the domain of random sequence generation was judged to be at high risk in every study. Allocation concealment was also mostly rated as high risk due to the lack of random assignment. Blinding of participants was consistently considered high risk, as it is practically impossible to blind transfusion procedures in these settings. The level of blinding for outcome assessment differed between studies. In contrast, all studies generally rated incomplete outcome data and selective reporting as low risk. Other potential biases were linked to study design factors, such as before-and-after comparisons, time-related effects, and uneven exposure between groups, centre-specific reporting differences, and possible industry involvement. No study achieved a low risk of bias across all domains; each had at least one domain rated as high risk.

Discussion

Summary of evidence on pathogen reduction and transfusion safety

This review confirms that PRTs, especially the amotosalen/UVA-based INTERCEPT® system, markedly reduce the risk of TTIs, providing strong evidence that PRTs help lower residual infection risks even after standard donor screening.

In contrast, the overall rate of TRAE was not significantly different between PRT-treated and conventional platelet transfusions. The high variability among studies likely reflects differences in their design, patient populations, and outcome definitions, which may have masked more minor but clinically meaningful effects. Overall, while PRT helps reduce infection-related complications, its impact on non-infectious adverse events appears minimal or neutral.

Differential effects on specific transfusion reactions

Subgroup analyses revealed that PRT-treated platelets were less likely to have several clinically significant reactions, including ATR, SAR, TACO, and TRALI. These findings suggest that PRT may attenuate inflammatory or immune-mediated transfusion responses beyond pathogen inactivation.

Mechanistically, this effect may be partly attributed to the inactivation of residual leukocytes within blood products during PRT processing. PRT systems may induce covalent modifications in nucleic acids that impair donor leukocytes' viability and immunological function while preserving plasma protein integrity [40]. This effect has been observed in vitro as reduced cytokine release and diminished antigen-presenting cell activity, which may, in turn, attenuate immune-mediated reactions following transfusion [41,42]. Notably, PRTs have been shown to inactivate nearly 100% of leukocytes in treated blood components, with a specific effect on T lymphocyte inactivation equivalent to or even superior to â?-irradiation [43]. Consequently, the observed reduction in inflammatory adverse events (e.g., ATR, TRALI) may reflect both pathogen inactivation and secondary immunomodulatory effects related to leukocyte dysfunction; however, this mechanism has not yet been confirmed in clinical studies.

As the non-PRT data from all included studies were collected nearly two decades ago, the observed reduction in TACO incidence may not be solely attributable to the implementation of PRT. Improvements in clinical transfusion practices over time-with physicians and nurses becoming more cautious in fluid management and monitoring-are also likely to have contributed [35].

By contrast, the incidence of FNHTRs did not differ significantly between PRT-treated and conventional platelet transfusions, accompanied by considerable heterogeneity (I²=98%). FNHTRs are primarily driven by soluble cytokines and pyrogenic mediators accumulated during platelet storage, rather than by activating viable leukocytes, which explains the limited impact of PRT on their occurrence [44]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the immunomodulatory properties of PRT systems may contribute to a selective reduction in immune-mediated transfusion reactions, whereas cytokine-mediated febrile responses appear largely unaffected.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Although PRTs have been available for over two decades, their global use is still limited. The different ways these systems work may also lead to varied clinical outcomes. Evidence from two randomised controlled non-inferiority trials comparing INTERCEPT® and Mirasol® treated platelets with standard products did not show clear statistical non-inferiority because the studies had limited power. Even so, the results offered indirect support for the safety and effectiveness of both systems [45].

The Corrected Count Increment (CCI) is a standardised indicator of platelet transfusion efficacy. It adjusts for the patient’s body surface area and the platelet dose received. Although PRTs such as INTERCEPT® may theoretically impair platelet recovery and survival through photochemical modifications of membrane proteins, this could reduce CCI and increase the potential need for more frequent transfusions. However, clinical evidence has not been consistent. Early small-scale trials reported slightly lower CCIs and higher platelet utilisation among patients receiving PRT-treated platelets [31,46]. However, larger multicentre studies have not confirmed these findings, most of which have shown no significant increase in platelet consumption compared with conventional platelets [47,48].

Because of limits in resources, humanitarian priorities, and logistics, clinical data on TTIs remain limited. Only one randomised controlled trial demonstrated that PRT effectively reduces the incidence of TTIs [49]. In regions with endemic infectious diseases, PRT represents a proactive strategy to mitigate the risk associated with “unsafe” blood donations and to sustain the availability of blood supplies. However, such regions are often resource-limited, and implementing PRT substantially increases operational costs. A cost analysis conducted in Italy estimated an overall cost increase of approximately 30% following PRT implementation [15]. In contrast, Rosskopf et al. reported that eliminating gamma irradiation and bacterial screening during PRT implementation could reduce the net cost increase to only 7.5% [50]. Similarly, Grégoire, et al. in Quebec found an Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) of approximately USD 8.1 million per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY), which markedly decreased to USD 123,063 when a new transfusion-transmissible pathogen was assumed [51]. These findings suggest that replacing specific routine screening steps with PRT may sustain a safe blood supply at a modest and potentially acceptable increase in overall cost in regions with a high infectious burden.

To date, clinical centres that use PRTs have not reported any significant increase in TRAEs. Their continued routine use supports these systems' overall safety and clinical utility. Nevertheless, global adoption remains limited, primarily due to the lack of robust randomised controlled trials that rigorously evaluate transfusion efficacy, long-term safety, and patient-centred outcomes. Further high-quality investigations are needed to clarify the potential risks of PRT across diverse clinical and epidemiological contexts, including rare adverse events and the cumulative effects of repeated transfusions. At the same time, future work should focus on making PRT systems more cost-effective and practical. Technological improvements that reduce reagent use, energy needs, and equipment costs could make these systems more accessible and sustainable, especially in low- and middle-income regions where transfusion-transmitted infections remain common.

Strengths and limitations of the review

Although this review provides a clear summary of current evidence on PRTs in transfusion medicine, several significant limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. The review included studies from three major databases and followed a systematic PRISMA-based approach, but only English-language publications available through institutional databases were included. As a result, some relevant regional reports or non-indexed haemovigilance data may have been missing. All included studies focused on the INTERCEPT® amotosalen/UVA system applied to platelet products, so direct comparisons were limited to this platform. Therefore, the findings may not directly apply to other PRT systems or blood components and should be interpreted cautiously.

Furthermore, most included studies were retrospective, and only a few provided randomised data to confirm causal relationships. There was considerable variation between studies, especially in how transfusion-related adverse events were defined and classified. This may have affected the precision of the pooled estimates. In addition, only a few studies reported detailed data on non-infectious transfusion reactions. This reduced the statistical power of subgroup analyses. The studies also involved very different patient populations. They varied in age, clinical setting, and transfusion indications. These differences likely affected the comparability of outcomes and may have contributed to the variability seen in adverse reaction rates.

Despite these limitations, this review is one of the few that quantitatively examined infectious and non-infectious transfusion outcomes associated with PRT-treated platelets. The consistent finding of reduced risk of TTIs supports the value of PRT as an effective safety intervention. However, further large-scale randomised trials are still needed to confirm these findings and strengthen the evidence base.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that PRTs, particularly the amotosalen/UVA-based INTERCEPT® system, significantly reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections while maintaining overall transfusion safety. And there is no consistent evidence of increased non-infectious adverse reactions. These findings highlight PRT as an effective adjunct to existing donor screening and pathogen testing, reinforcing its value in modern transfusion practice.

However, current evidence is limited by the predominance of observational data, a focus on platelets, and the scarcity of long-term outcome assessments, which restrict generalisability. Future multicentre randomised trials and health-economic evaluations are essential to validate these findings across diverse blood products and healthcare settings. Broader implementation of cost-effective PRT platforms could strengthen public health preparedness and enhance community-level transfusion safety worldwide.

Funding Statement

The authors received no financial support for the research.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

References

- Jersild C, Hafner V. Blood transfusion services. Int Encycl Public Health. 2016;247.

- Darby SC, Kan SW, Spooner RJ, Giangrande PL, Hill FG, Hay CR, et al. Mortality rates, life expectancy, and causes of death in people with hemophilia A or B in the United Kingdom who were not infected with HIV. Blood. 2007;110(3):815-825.

- Busch MP, Bloch EM, Kleinman S. Prevention of transfusion-transmitted infections. Blood. 2019;133(17):1854-1864.

- Stramer SL, Dodd RY, Subgroup D. Transfusionâ?transmitted emerging infectious diseases: 30 years of challenges and progress. Transfusion. 2013;53(10):2375.

- Dodd RY. Current risk for transfusion transmitted infections. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(6):671-676.

- Janka J, Maldarelli F. Prion diseases: Update on mad cow disease, variant creutzfeldt-jakob disease, and the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2004;6(4):305-315.

- Klein HG. Will blood transfusion ever be safe enough? JAMA. 2000;284(2):238-240.

- Chozie NA, Satiti MA, Sjarif DR, Oswari H, Ritchie NK. The impact of nucleic acid testing as a blood donor screening method in transfusion-associated hepatitis C among children with bleeding disorders in Indonesia: A single-center experience. Blood Res. 2022;57(2):129-134.

- Cohn CS, Delaney M, Johnson ST, Katz LM, Schwartz J. AABB technical manual. Bethesda, Maryland, USA: AABB. 2020:297-328.

- Candotti D, Laperche S. Hepatitis B virus blood screening: Need for reappraisal of blood safety measures?. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:29.

- Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, Van Der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1967-1976.

- Moor AC, Dubbelman TM, VanSteveninck J, Brand A. Transfusionâ?transmitted diseases: Risks, prevention and perspectives. Eur J Haematol. 1999;62(1):1-8.

- Marschner S, Goodrich R. Pathogen reduction technology treatment of platelets, plasma and whole blood using riboflavin and UV light. Transfus Med Hemother. 2011;38(1):8-18.

- Corean J, White SK, Schmidt RL, Walker BS, Fisher MA, Metcalf RA. Platelet component false positive detection rate in aerobic and anaerobic primary culture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus Med Rev. 2021;35(3):44-52.

- Cicchetti A, Coretti S, Sacco F, Rebulla P, Fiore A, Rumi F, et al. Budget impact of implementing platelet pathogen reduction into the Italian blood transfusion system. Blood Transfus. 2018;16(6):483.

- Yonemura S, Doane S, Keil S, Goodrich R, Pidcoke H, Cardoso M. Improving the safety of whole blood-derived transfusion products with a riboflavin-based pathogen reduction technology. Blood Transfus. 2017;15(4):357.

- Mundt JM, Rouse L, Van den Bossche J, Goodrich RP. Chemical and biological mechanisms of pathogen reduction technologies. Photochem Photobiol. 2014;90(5):957-964.

- Kaiser-Guignard J, Canellini G, Lion N, Abonnenc M, Osselaer JC, Tissot JD. The clinical and biological impact of new pathogen inactivation technologies on platelet concentrates. Blood Rev. 2014;28(6):235-241.

- Piccin A, Allameddine A, Spizzo G, Lappin KM, Prati D. Platelet pathogen reduction technology-should we stay or should we go…?. J Clin Med. 2024;13(18):5359.

- Chen L, Yao M. Pathogen inactivation plays an irreplaceable role in safeguarding the safety of blood transfusion. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 2016;8.

- Sobral PM, Barros AE, Gomes AM, Bonfim CV. Viral inactivation in hemotherapy: Systematic review on inactivators with action on nucleic acids. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2012;34:231-235.

- Drew VJ, Barro L, Seghatchian J, Burnouf T. Towards pathogen inactivation of red blood cells and whole blood targeting viral DNA/RNA: Design, technologies, and future prospects for developing countries. Blood Transfus. 2017;15(6):512.

- Gathof BS, Tauszig ME, Picker SM. Pathogen inactivation/reduction of platelet concentrates: turning theory into practice. ISBT Sci Ser. 2010;5(1):114-119.

- Lozano M, Cid J. Platelet concentrates: Balancing between efficacy and safety?. Presse Med. 2016;45(7-8):e289-298.

- Schlenke P. Pathogen inactivation technologies for cellular blood components: An update. Transfus Med Hemother. 2014;41(4):309-325.

- Schulze TJ, Gravemann U, Seltsam A. THERAFLEX ultraviolet C (UVC)-based pathogen reduction technology for bacterial inactivation in blood components: Advantages and limitations. Ann Blood. 2022;7.

- LaFontaine PR, Yuan J, Prioli KM, Shah P, Herman JH, Pizzi LT. Economic analyses of pathogen-reduction technologies in blood transfusion: A systematic literature review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(4):487-499.

- Walsh GM, Shih AW, Solh Z, Golder M, Schubert P, Fearon M, et al. Blood-borne pathogens: A Canadian blood services centre for innovation symposium. Transfus Med Rev. 2016;30(2):53-68.

- Tormey CA, Santhanakrishnan M, Smith NH, Liu J, Marschner S, Goodrich RP, et al. Riboflavinâ?ultraviolet light pathogen reduction treatment does not impact the immunogenicity of murine red blood cells. Transfusion. 2016;56(4):863-872.

- Pati I, Masiello F, Pupella S, Cruciani M, De Angelis V. Efficacy and safety of pathogen-reduced platelets compared with standard apheresis platelets: A systematic review of RCTs. Pathogens. 2022;11(6):639.

- Osselaer JC, Doyen C, Defoin L, Debry C, Goffaux M, Messe N, et al. Universal adoption of pathogen inactivation of platelet components: Impact on platelet and red blood cell component use. Transfusion. 2009;49(7):1412-1422.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008; 61(4):344-349.

- Amato M, Schennach H, Astl M, Chen CY, Lin JS, Benjamin RJ, et al. Impact of platelet pathogen inactivation on blood component utilization and patient safety in a large Austrian regional medical centre. Vox Sang. 2017;112(1):47-55.

- Andreu G, Boudjedir K, Meyer N, Carlier M, Drouet C, Py JY, et al. Platelet additive solutions and pathogen reduction impact on transfusion safety, patient management and platelet supply. Transfus Med Rev. 2025;150875.

- Lasky B, Nolasco J, Graff J, Ward DC, Ziman A, McGonigle AM. Pathogenâ?reduced platelets in pediatric and neonatal patients: Demographics, transfusion rates, and transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2021;61(10):2869-2876.

- Mowla SJ, Kracalik IT, Sapiano MR, O'Hearn L, Andrzejewski Jr C, Basavaraju SV. A comparison of transfusion-related adverse reactions among apheresis platelets, whole blood-derived platelets, and platelets subjected to pathogen reduction technology as reported to the national healthcare safety network Hemovigilance module. Transfus Med Rev. 2021;35(2):78-84.

- Richard P, Pouchol E, Sandid I, Aoustin L, Lefort C, Chartois AG, et al. Implementation of amotosalen plus ultraviolet Aâ?mediated pathogen reduction for all platelet concentrates in France: Impact on the risk of transfusionâ?transmitted infections. Vox Sang. 2024;119(3):212-218.

- Snyder EL, Wheeler AP, Refaai M, Cohn CS, Poisson J, Fontaine M, et al. Comparative risk of pulmonary adverse events with transfusion of pathogen reduced and conventional platelet components. Transfusion. 2022;62(7):1365-1376.

- Lin L, Dikeman R, Molini B, Lukehart SA, Lane R, Dupuis K, et al. Photochemical treatment of platelet concentrates with amotosalen and long-wavelength ultraviolet light inactivates a broad spectrum of pathogenic bacteria. Transfusion. 2004;44(10):1496-1504.

- Fast LD, DiLeone G, Li J, Goodrich R. Functional inactivation of white blood cells by Mirasol treatment. Transfusion. 2006;46(4):642-648.

- Picker SM, Oustianskaia L, Schneider V, Gathof BS. Functional characteristics of apheresisâ?derived platelets treated with ultraviolet light combined with either amotosalenâ?HCl (Sâ?59) or riboflavin (vitamin B2) for pathogenâ?reduction. Vox sanguinis. 2009;97(1):26-33.

- Li M, Irsch J, Corash L, Benjamin RJ. Is pathogen reduction an acceptable alternative to irradiation for risk mitigation of transfusion-associated graft versus host disease?. Transfus Apher Sci. 2022;61(2):103404.

- Goel R, Tobian AA, Shaz BH. Noninfectious transfusion-associated adverse events and their mitigation strategies. Blood. 2019;133(17):1831-1839.

- Rebulla P, Vaglio S, Beccaria F, Bonfichi M, Carella A, Chiurazzi F, et al. Clinical effectiveness of platelets in additive solution treated with two commercial pathogenâ?reduction technologies. Transfusion. 2017;57(5):1171-1183.

- Murphy S, Snyder E, Cable R, Slichter SJ, Strauss RG, McCullough J, et al. Platelet dose consistency and its effect on the number of platelet transfusions for support of thrombocytopenia: An analysis of the SPRINT trial of platelets photochemically treated with amotosalen HCl and ultraviolet A light. Transfusion. 2006;46(1):24-33.

- Cazenave JP, Isola H, Waller C, Mendel I, Kientz D, Laforêt M, et al. Use of additive solutions and pathogen inactivation treatment of platelet components in a regional blood center: Impact on patient outcomes and component utilization during a 3â?year period. Transfusion. 2011;51(3):622-629.

- Infanti L, Holbro A, Passweg J, Bolliger D, Tsakiris DA, Merki R, et al. Clinical impact of amotosalenâ?ultraviolet a pathogenâ?inactivated platelets stored for up to 7 days. Transfusion. 2019;59(11):3350-3361.

- Allain JP, Owusu-Ofori AK, Assennato SM, Marschner S, Goodrich RP, Owusu-Ofori S. Effect of Plasmodium inactivation in whole blood on the incidence of blood transfusion-transmitted malaria in endemic regions: the African Investigation of the Mirasol System (AIMS) randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 Apr;387(10029):1753-1761.

- Rosskopf K, Helmberg W, Schlenke P. Pathogen reduction of doubleâ?dose platelet concentrates from pools of eight buffy coats: Product quality, safety, and economic aspects. Transfusion. 2020;60(9):2058-2066.

- Grégoire Y, Delage G, Custer B, Rochette S, Renaud C, Lewin A, et al. Costâ?effectiveness of pathogen reduction technology for plasma and platelets in Québec: A focus on potential emerging pathogens. Transfusion. 2022;62(6):1208-1217.

Citation: Gao J, Jackson DE. (2025). Effectiveness of Pathogen Reduction Techniques in Fresh Blood Products for Enhancing Community Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Blood Disord Transfus. 16:629.

Copyright: © 2025 Gao J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.