Indexed In

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- SWB online catalog

- Publons

- International committee of medical journals editors (ICMJE)

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

Useful Links

Share This Page

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2016) Volume 19, Issue 4

Work-Related Stress and Stress-Coping Strategies among Patients Companions at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Providing care to hospitalized patients may be associated with stress, reduced quality of life, and even psychiatric disorders. This case-control study aimed to compare the level of stress (using the 14-question perceived stress scale (PSS-14), potential risk factors, and stress-coping strategies (using the 28-item brief coping scale (BCS-28) between two convenient samples of patients’ companions (56) and administrative employees (98) working in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. The average PSS-14 was slightly higher in companions than administrative employees (27.4 ± 9.9 vs. 25.1 ± 10.1, p=0.179). After stratifying by gender, the difference in males (but not females) was marginally significant in the unadjusted comparison and significant in the adjusted comparison. Companions had similar scores of adaptive stress-coping strategies but higher scores of maladaptive stress-coping strategies compared with administrative employees. This was especially apparent in the denial and self-distraction strategies. PSS-14 in all participants had a moderate significant positive correlation with maladaptive stress-coping strategies. Companions exhibited a gender-specific slight increase in the level of stress and adopted more maladaptive stresscoping strategies compared with administrative employees. There were no group differences in blood lipids, serum glucose, or cortisol levels.

Keywords: Companions; Administrative; Stress; Coping; Gender; Saudi Arabia

Introduction

The concept of “constant observation” refers to continuous one-toone monitoring that is used to assure the safety and well-being of patients [1]. In the West, this is usually achieved by allocated nurses, hired or volunteer non-relative personnel, or patient family members [2]. In Saudi Arabia, a companion refers to the person (usually a family member or a friend) who provides “constant observation” for a patient during his/ her stay at the hospital [3,4]. In the literature, several terminologies are used interchangeably with companion, such as patient sitter and patient attendant [5]. The companion policy at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) defines a companion as a healthy adult (more than 18 years of age) who is not overtly pregnant or taking care of infants. The policy allows one companion for children, senior and disabled patients, but does not allow companions for patients in critical care areas or for isolated patients due to the risk of infection and medical-related issues.

Several studies showed that family caregiving to patients with different disabling diseases are associated with high levels of distress, reduced quality of life, and even psychiatric disorders among the caregivers [6-8]. On the other hand, a limited number of studies examined the psychological impact of caregiving on the companions of patients with chronic and aging diseases admitted to hospitals [9-11]. Although this type of data is critical for any future attempt to improve the effectiveness of the current companion policy [3,12], data examining stress and stress-coping strategies among patient companions in Saudi Arabia are largely lacking. The objective of the current study was to compare the level of stress, potential risk factors, and stress-coping strategies among companions in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Similar to previous studies, administrative employees working in the same hospital were used as a control group [13].

Methods

Population

The current study was conducted among companions and administrative employees at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. KKUH is an 800-bed Universityaffiliated government hospital that provides free primary to tertiary care services to residents of the Northern Riyadh area. The KKUH provides inpatient services for more than 50,000patients per year. Companions who were non-healthcare sitters/caregivers of admitted patients were invited to join the study during their stay in the hospital. The KKUH hired approximately 3,000 administrative employees at the time of the study. Administrative employees with no clinical responsibilities or direct patient contact, such as accountants and receptionists, were invited to join the study.

Study design

A case-control study was carried out between December 2013 and June 2014. The study obtained all of the required ethical approvals from the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Medicine at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Sample size and recruitment

Previous studies that used the 14-question perceived stress scale (PSS-14) showed that the average score was 25 ± 8 points [14]. Having two administrative employees for each companion, it was estimated that 48 companions and 96 administrative employees are required to detect a 4 point difference (23-27) between the groups, with 80% power and a level of significance of 95%. The study participants were a convenient sample of companions who were personally invited to join the study. An age-matched control group of administrative employees who were working at KKUH during the study period were invited to join the study, either personally or by email.

Data collection tool

The self-administered questionnaire that was developed included socio-demographic characteristics, clinical history, occupational characteristics, and recently faced stressors. The perception of stress over the past month was assessed using PSS-14 [15,16]. Each question was answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale (never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often, or very often) and was given a score (ranging from 0 to 4). The PSS-14 score was calculated by summing the scores of individual questions, with higher scores representing higher levels of stress (possible range between 0 and 56 points). The scores of seven questions (4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13) were reversed as they were positively stated. Stress-coping strategies employed in the past month were assessed using the 28-item brief coping scale (BCS-28) [17]. Each question was answered on a 4-point Likert-type scale (not at all, a little bit, a medium amount, or a lot). Each question was given a score ranging from 1 to 4 and each strategy was given a score ranging from 2 to 8. The scale assesses 14 stress-coping strategies using 28 questions (2 questions per strategy). Stress-coping strategies were grouped into adaptive or maladaptive strategies, as described previously [18]. Standing height (in cm) and weight (in kg) while the participant is wearing light clothes with bared feet were measured and used in calculating BMI (height /weight2). Waist circumference (in cm) at the level of umbilicus was measured while the participant is standing and comfortably breathing. Blood pressure was recorded by using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after the subject seats for at least 5 minutes. Two readings will be taken with 5 minutes interval and their mean will be recorded. For biochemical investigations, a venous blood sample was taken in the morning after an eight hours fasting for the determination of blood lipids (Low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides), fasting blood glucose, and cortisol.

Validation of data collection tool

Because the majority of companions and administrative employees do not speak English, the study questionnaire and both scales were first translated into Arabic by a linguistic specialist, fluent in both English and Arabic. Then, another specialist, fluent in both English and Arabic, carried out back translation into English. During this time, the backtranslation and the original scale were compared and any differences were discussed and resolved. The content of the study questionnaire was validated by experts in psychiatry, epidemiology and ethics to ensure the relevance and applicability of different questions. The study questionnaire and both scales were then piloted on 15 individuals before the study began. The wording and suggested answers were modified for some questions based on the feedback from the pilot sample. Both PSS-14 [19,20] and BCS-28 [21] have been shown to be valid tools for perceived stress and stress-coping strategies, respectively. In the current study, the overall PSS-14 as well as the adaptive and non-adaptive BCS- 28 had acceptable internal consistency among their items, as indicated by overall Cranach Alpha values of 0.83, 0.77, and 0.64, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical data and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous data. Significant differences between companions and administrative employees in PSS-14, BCS-28, socio-demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and occupational characteristics were tested using Student’s t-test for continuous data and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (as appropriate) for categorical data. The adjusted marginal means of PSS by study groups and gender were calculated using a general linear model. The correlations between PSS-14 and BCS-28 were examined using Spearman’s correlation. All p-values were two-tailed. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. SPSS software (release 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, U.S.) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

A total of 154 participants (56 companions and 98 administrative employees) completed the study questionnaire and both the PSS-14 and coping scales. As shown in Table 1, the average age was 28.5 ± 4.5 years with almost two-thirds (64%) of the participants below the age of 30. Females represented 57% of the participants, with more females among the companions than the administrative employees (74% vs. 47%). All participants were Saudi, and approximately half (51%) of them were currently married. Obesity parameters including body mass index (BMI) (31.3 ± 6.7 vs. 26.6 ± 5.2), waist circumference (86.6 ± 14.8 vs. 79.6 ± 13.5), and the prevalence of obesity (56.1% vs. 24.5%) were much higher in the companions compared with the administrative employees. There were more current smokers among the administrative employees (26%) compared with the companions (11%). Approximately 34% of the participants had chronic medical illnesses, which primarily included obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Approximately 22% of the participants had a past history of psychiatric illness; 19% received psychiatric help and 11% had a family history of psychiatric illness. On examination, 29% of the participants had a psychiatric illness, which primarily included major depressive episodes, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. The average SBP was 115.1 ± 13.2 mmHg and the average DBP was 75.6 ± 8.7 mmHg. Compared with the administrative employees, the companions were older (p=0.009), more likely to be female (p=0.002), and had higher BMI (p<0.001), waist circumference (p=0.003), prevalence of obesity (<0.001), and history of hypertension (p=0.024); however, the companions were less likely to smoke (p=0.024) and had lower SBP (p=0.007). There were no group differences in blood lipids, serum glucose, or cortisol levels.

| Companions (N=56) | Administrative employees (N=98) | Total (N=154) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 29.34.4 | 28.1 ± 4.6 | 28.5 ± 4.5 | 0.098 |

| <27 | 19 (33.9%) | 37 (38.5%) | 56 (36.8%) | 0.009 |

| 27-29 | 9 (16.1%) | 32 (33.3%) | 41 (27.0%) | |

| >29 | 28 (50.0%) | 27 (28.1%) | 55 (36.2%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 15 (26.3%) | 54 (52.9%) | 69 (43.4%) | 0.002 |

| Female | 42 (73.7%) | 48 (47.1%) | 90 (56.6%) | |

| BMI | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 31.3 ± 6.7 | 26.6 ± 5.2 | 28.4 ± 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Normal | 9 (15.8%) | 44 (43.1%) | 53 (33.3%) | <0.001 |

| Overweight | 16 (28.1%) | 33 (32.4%) | 49 (30.8%) | |

| Obese | 32 (56.1%) | 25 (24.5%) | 57 (35.8%) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 86.6 ± 14.8 | 79.6 ± 13.5 | 82.1 ± 14.3 | 0.003 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 30 (53.6%) | 48 (49.0%) | 78 (50.6%) | 0.341 |

| single | 22 (39.3%) | 47 (48.0%) | 69 (44.8%) | |

| Divorced | 4 (7.1%) | 3 (3.1%) | 7 (4.5%) | |

| Medical and behavioral history | ||||

| Comorbidity | 22 (39.3%) | 31 (31.6%) | 53 (34.4%) | 0.38 |

| Diabetes | 6 (10.7%) | 3 (3.1%) | 9 (5.8%) | 0.073 |

| Hypertension | 5 (8.9%) | 1 (1.0%) | 6 (3.9%) | 0.024 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (1.8%) | 5 (5.1%) | 6 (3.9%) | 0.417 |

| Obesity | 4 (7.1%) | 12 (12.2%) | 16 (10.4%) | 0.318 |

| Others | 9 (16.1%) | 14 (14.3%) | 23 (14.9%) | 0.765 |

| Current smoking | 6 (10.7%) | 25 (26.0%) | 31 (20.4%) | 0.024 |

| History of psychiatric illness | ||||

| Personal history of psychiatric illness | 11 (19.6%) | 22 (22.7%) | 33 (21.6%) | 0.66 |

| Received psychiatric help | 10 (17.9%) | 19 (19.6%) | 29 (19.0%) | 0.792 |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | 7 (12.7%) | 10 (10.5%) | 17 (11.3%) | 0.682 |

| Diagnosis of psychiatric illness | ||||

| No | 37 (67.3%) | 70 (72.9%) | 107 (70.9%) | 0.463 |

| Yes | 18 (32.7%) | 26 (27.1%) | 44 (29.1%) | |

| Major depressive episode | 13 (23.6%) | 14 (14.6%) | 27 (17.9%) | 0.162 |

| Panic disorder | 2 (3.6%) | 4 (4.2%) | 6 (4.0%) | 1 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.1%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0.534 |

| Others | 3 (5.5%) | 6 (6.2%) | 9 (6.0%) | 1 |

| Blood pressure measurement | ||||

| Average SBP (mmHg) | 111.3 ± 12.2 | 117.3 ± 13.4 | 115.1 ± 13.2 | 0.007 |

| Average DBP (mmHg) | 75.5 ± 8.0 | 75.7 ± 9.1 | 75.6 ± 8.7 | 0.905 |

| Blood examination | ||||

| LDL cholesterol (nmol/L) | 2.39 ± 0.71 | 2.49 ± 0.82 | 2.45 ± 0.78 | 0.477 |

| HDL cholesterol (nmol/L) | 1.23 ± 0.32 | 1.25 ± 0.36 | 1.24 ± 0.34 | 0.766 |

| Triglycerides (nmol/L) | 1.13 ± 0.55 | 1.06 ± 0.79 | 1.09 ± 0.71 | 0.543 |

| Total cholesterol (nmol/L) | 4.76 ± 0.84 | 4.79 ± 0.86 | 4.78 ± 0.85 | 0.791 |

| Fasting blood glucose (nmol/L) | 5.05 ± 1.78 | 4.80 ± 2.96 | 4.89 ± 2.59 | 0.572 |

| Cortisol (nmol/L) | 411.4 ± 169.4 | 392.7 ± 151.7 | 399.5 ± 158.1 | 0.483 |

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics by study groups.

As shown in Table 2, approximately 55% of the participants had a monthly income between SR 5,000 and SR 9,999. While the income was lower in the companions compared with the administrative employees, both were equally satisfied (57%) with their income. The majority of the participants were sleeping less than 7 hours per day (63%) and working less than 8 hours per day (59%). More than half (55%) of the participants considered their job stressful and the majority (54%) had (always/sometimes) thoughts of changing their job or specialty. The majority (87%) of the participants reported facing stressors during the last month. These included work-related stressors (34%) followed by financial (33%), family (31%), and other stressors. Only 33% of the participants had training in stress management. Approximately 10% of the participants had (always/sometimes) suicidal thoughts and 4% had thoughts of harming themselves. Compared to the administrative employees, the companions had lower income (p=0.048), worked fewer hours (p<0.001), faced less work-related stressors (p<0.001), had more thoughts about changing their job/specialty (p=0.001), and had more suicidal thoughts (0.006).

| Companions (N=56) | Administrative employees (N=98) | Total (N=154) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly income (SR) | ||||

| < 5,000 | 15 (27.8%) | 10 (10.2%) | 25 (16.4%) | 0.048 |

| 5,000 – 9,999 | 25 (46.3%) | 59 (60.2%) | 84 (55.3%) | |

| 10,000 – 14,999 | 10 (18.5%) | 21 (21.4%) | 31 (20.4%) | |

| ≥15,000 | 4 (7.4%) | 8 (8.2%) | 12 (7.9%) | |

| Satisfied with the income | ||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 30 (54.5%) | 56 (58.3%) | 86 (57.0%) | 0.87 |

| Not sure | 7 (12.7%) | 10 (10.4%) | 17 (11.3%) | |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 18 (32.7%) | 30 (31.2%) | 48 (31.8%) | |

| Average sleeping per day | ||||

| <7 hours | 33 (60.0%) | 63 (64.3%) | 96 (62.7%) | 0.131 |

| 7-8 hours | 18 (32.7%) | 34 (34.7%) | 52 (34.0%) | |

| > 8 hours | 4 (7.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 5 (3.3%) | |

| Working hours per day | ||||

| ≤8 hours | 46 (83.6%) | 44 (44.9%) | 90 (58.8%) | <0.001 |

| >8 hours | 9 (16.4%) | 54 (55.1%) | 63 (41.2%) | |

| Working weekends | ||||

| No | 29 (55.8%) | 69 (70.4%) | 98 (65.3%) | 0.073 |

| Yes | 23 (44.2%) | 29 (29.6%) | 52 (34.7%) | |

| Consider job stressful | ||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 28 (50.0%) | 56 (57.1%) | 84 (54.5%) | 0.657 |

| Not sure | 9 (16.1%) | 12 (12.2%) | 21 (13.6%) | |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 19 (33.9%) | 30 (30.6%) | 49 (31.8%) | |

| Facing stressors during last month | ||||

| No | 7 (12.5%) | 13 (13.3%) | 20 (13.0%) | 1 |

| Yes | 49 (87.5%) | 85 (86.7%) | 134 (87.0%) | |

| Work | 9 (16.1%) | 43 (43.9%) | 52 (33.8%) | <0.001 |

| Financial | 17 (30.4%) | 33 (33.7%) | 50 (32.5%) | 0.672 |

| Family | 21 (37.5%) | 27 (27.6%) | 48 (31.2%) | 0.2 |

| Marital | 7 (12.5%) | 13 (13.3%) | 20 (13.0%) | 0.892 |

| Academic | 4 (7.1%) | 13 (13.3%) | 17 (11.0%) | 0.243 |

| Death of loved person | 5 (8.9%) | 11 (11.2%) | 16 (10.4%) | 0.653 |

| Household sick person | 8 (14.3%) | 5 (5.1%) | 13 (8.4%) | 0.069 |

| Trained in stress management | ||||

| No | 39 (69.6%) | 63 (65.6%) | 102 (67.1%) | 0.611 |

| Yes | 17 (30.4%) | 33 (34.4%) | 50 (32.9%) | |

| Thoughts/wishes* | ||||

| To change job/specialty | 40 (71.4%) | 43 (43.9%) | 83 (53.9%) | 0.001 |

| To die | 11 (19.6%) | 5 (5.1%) | 16 (10.4%) | 0.006 |

| To harm own-self | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (3.1%) | 6 (3.9%) | 0.668 |

*Always or sometimes

Table 2: Work-related characteristics, stressors, and ideations by study groups.

Table 3 shows the actual answers to the PSS-14 questions from both companions and administrative employees. Some responses were similar in both groups. For example, more than 60% of the participants in both groups were fairly/very often thinking about things that they needed to accomplish. On the other hand, several questions were answered with opposing responses in each of the groups. For example, 64% of the companions, compared with 46% of the administrative employees, were fairly/very often feeling nervous and stressed.

| S. No | Companions (N=56) | Administrative employees (N=98) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the last month, how often have you been | Never | Almost never | Sometimes | Fairly often | Very often | Never | Almost never | Sometimes | Fairly often | Very often | |

| 1 | Upset because of something that happened unexpectedly | 8 (14.5%) | 6 (10.9%) | 17 (30.9%) | 15 (27.3%) | 9 (16.4%) | 12 (12.2%) | 18 (18.4%) | 35 (35.7%) | 18 (18.4%) | 15 (15.3%) |

| 2 | Feeling that you were unable to control the important things in your life | 10 (18.2%) | 9 (16.4%) | 18 (32.7%) | 9 (16.4%) | 9 (16.4%) | 27 (27.6%) | 25 (25.5%) | 22 (22.4%) | 15 (15.3%) | 9 (9.2%) |

| 3 | Feeling nervous and “stressed” | 4 (7.3%) | 4 (7.3%) | 12 (21.8%) | 11 (20.0%) | 24 (43.6%) | 10 (10.2%) | 9 (9.2%) | 34 (34.7%) | 17 (17.3%) | 28 (28.6%) |

| 4 | Dealing successfully with day to day problems and annoyances | 7 (12.7%) | 6 (10.9%) | 20 (36.4%) | 10 (18.2%) | 12 (21.8%) | 10 (10.3%) | 13 (13.4%) | 35 (36.1%) | 22 (22.7%) | 17 (17.5%) |

| 5 | Feeling that you were effectively coping with important changes that were occurring in your life | 7 (12.7%) | 11 (20.0%) | 8 (14.5%) | 10 (18.2%) | 19 (34.5%) | 9 (9.2%) | 11 (11.2%) | 14 (14.3%) | 29 (29.6%) | 35 (35.7%) |

| 6 | Feeling confident about your ability to handle your personal problems | 3 (5.6%) | 3 (5.6%) | 14 (25.9%) | 17 (31.5%) | 17 (31.5%) | 5 (5.1%) | 17 (17.3%) | 23 (23.5%) | 25 (25.5%) | 28 (28.6%) |

| 7 | Feeling that things were going your way | 11 (19.6%) | 6 (10.7%) | 20 (35.7%) | 11 (19.6%) | 8 (14.3%) | 8 (8.2%) | 20 (20.6%) | 30 (30.9%) | 25 (25.8%) | 14 (14.4%) |

| 8 | Finding that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do | 12 (21.8%) | 10 (18.2%) | 20 (36.4%) | 7 (12.7%) | 6 (10.9%) | 30 (30.9%) | 20 (20.6%) | 28 (28.9%) | 15 (15.5%) | 4 (4.1%) |

| 9 | Able to control irritations in your life | 7 (12.7%) | 9 (16.4%) | 17 (30.9%) | 8 (14.5%) | 14 (25.5%) | 7 (7.2%) | 15 (15.5%) | 23 (23.7%) | 27 (27.8%) | 25 (25.8%) |

| 10 | Feeling that you were on top of things | 4 (7.7%) | 10 (19.2%) | 16 (30.8%) | 11 (21.2%) | 11 (21.2%) | 8 (8.3%) | 15 (15.6%) | 40 (41.7%) | 20 (20.8%) | 13 (13.5%) |

| 11 | Angered because of things that happened that were outside of your control | 7 (13.0%) | 6 (11.1%) | 12 (22.2%) | 16 (29.6%) | 13 (24.1%) | 13 (13.5%) | 19 (19.8%) | 19 (19.8%) | 28 (29.2%) | 17 (17.7%) |

| 12 | Finding yourself thinking about things that you have to accomplish | 4 (7.4%) | 6 (11.1%) | 10 (18.5%) | 11 (20.4%) | 23 (42.6%) | 5 (5.2%) | 12 (12.5%) | 20 (20.8%) | 26 (27.1%) | 33 (34.4%) |

| 13 | Able to control the way you spend your time | 9 (16.1%) | 12 (21.4%) | 18 (32.1%) | 4 (7.1%) | 13 (23.2%) | 7 (7.2%) | 19 (19.6%) | 29 (29.9%) | 26 (26.8%) | 16 (16.5%) |

| 14 | Feeling difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them | 13 (23.2%) | 8 (14.3%) | 13 (23.2%) | 12 (21.4%) | 10 (17.9%) | 30 (30.9%) | 22 (22.7%) | 18 (18.6%) | 15 (15.5%) | 12 (12.4%) |

Table 3: Responses of companions and administrative employees to the items of perceived stress scale (PSS-14).

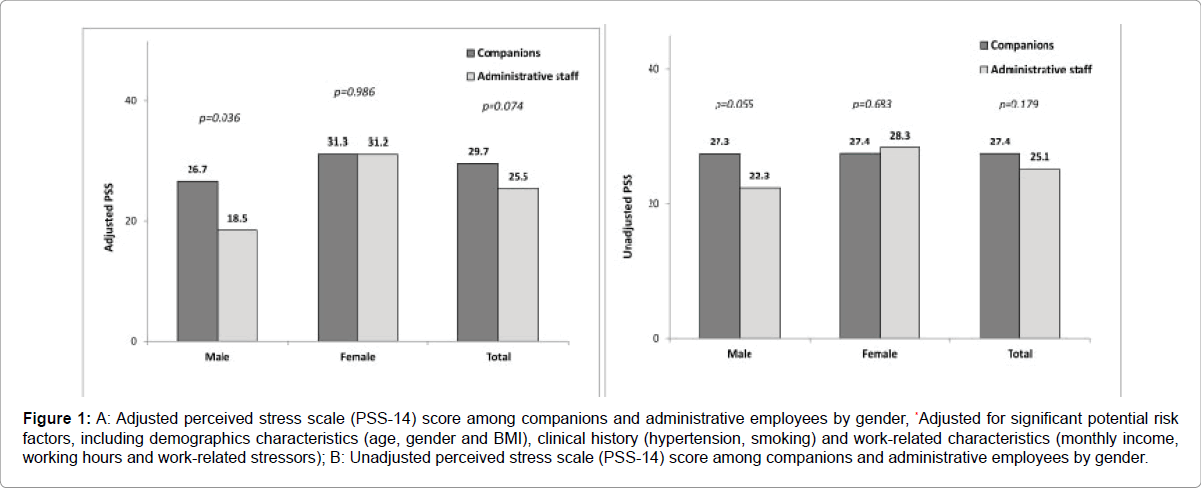

As shown in Figure 1, the average PSS-14 was slightly higher in companions than administrative employees (27.4 ± 9.9 vs. 25.1 ± 10.1); however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.179). After adjusting for the significant potential risk factors (shown in the univariate analysis above, which includes demographic, clinical, and work-related characteristics), the difference in PSS-14 widened and the p-value became marginally significant (29.7 vs. 25.5, p=0.074). Furthermore, after stratifying by gender, the difference in males (but not females) was marginally significant (p=0.055) in the unadjusted comparison and was significant (p=0.036) in the adjusted comparison.

Figure 1: A: Adjusted perceived stress scale (PSS-14) score among companions and administrative employees by gender, *Adjusted for significant potential risk factors, including demographics characteristics (age, gender and BMI), clinical history (hypertension, smoking) and work-related characteristics (monthly income, working hours and work-related stressors); B: Unadjusted perceived stress scale (PSS-14) score among companions and administrative employees by gender.

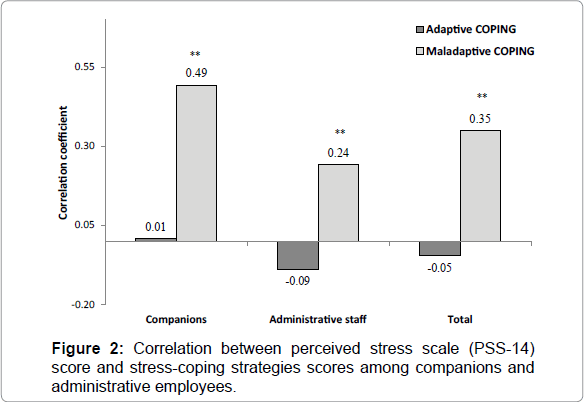

As shown in Table 4, the companions had similar scores of adaptive stress-coping strategies but higher scores of maladaptive stresscoping strategies compared with the administrative employees. This was especially apparent in the higher denial and self-distraction scores in the companions (p=0.006 and p=0.007, respectively). As shown in Figure 2, PSS-14 in all of the participants had a moderate significant positive correlation with maladaptive stress-coping strategies (rho=0.35, p<0.001) but a weak non-significant negative correlation with adaptive stress-coping strategies (rho=-0.05, p=0.572). The positive correlation between PSS-14 and maladaptive stress-coping strategies was higher among the companions compared with the administrative employees.

| Companions (N=56) | Administrative employees (N=98) | Total (N=154) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive stress-coping | 46.89 ± 7.73 | 45.98 ± 7.10 | 46.31 ± 7.32 | 0.458 |

| Active coping (2 and 7) | 5.79 ± 1.58 | 6.07 ± 1.58 | 5.97 ± 1.58 | 0.282 |

| Instrumental support (10 and 23) | 5.38 ± 1.54 | 5.60 ± 1.62 | 5.52 ± 1.59 | 0.396 |

| Planning (14 and 25) | 5.86 ± 1.72 | 6.06 ± 1.50 | 5.99 ± 1.58 | 0.442 |

| Acceptance (20 and 24) | 6.53 ± 1.43 | 6.17 ± 1.41 | 6.30 ± 1.42 | 0.141 |

| Emotional support (5 and 15) | 5.77 ± 1.57 | 5.22 ± 1.71 | 5.42 ± 1.68 | 0.053 |

| Humor (18 and 28) | 5.02 ± 2.05 | 4.79 ± 1.93 | 4.87 ± 1.97 | 0.484 |

| Positive reframing (12 and 17) | 6.13 ± 1.58 | 5.93 ± 1.52 | 6.00 ± 1.54 | 0.449 |

| Religion (22 and 27) | 6.67 ± 1.44 | 6.13 ± 1.77 | 6.33 ± 1.67 | 0.055 |

| Maladaptive stress-coping | 27.73 ± 4.34 | 25.87 ± 5.03 | 26.55 ± 4.86 | 0.021 |

| Behavioral disengagement (6 and 16) | 3.95 ± 1.69 | 3.66 ± 1.51 | 3.77 ± 1.58 | 0.286 |

| Denial (3 and 8) | 4.05 ± 1.60 | 3.37 ± 1.39 | 3.62 ± 1.50 | 0.006 |

| Self-distraction (1 and 19) | 6.18 ± 1.57 | 5.43 ± 1.67 | 5.70 ± 1.67 | 0.007 |

| Self-blame (13 and 26) | 5.91 ± 1.73 | 5.63 ± 1.85 | 5.73 ± 1.80 | 0.359 |

| Substance use (4 and 11) | 2.02 ± 0.13 | 2.12 ± 0.71 | 2.08 ± 0.57 | 0.276 |

| Venting (9 and 21) | 5.63 ± 1.48 | 5.65 ± 1.51 | 5.64 ± 1.50 | 0.911 |

Table 4: Differences in stress-coping strategies between companions and administrative employees.

Discussion

Here, we report a slight increase in the level of stress among companions compared to administrative employees in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. The slight increase in the level of stress among companions may be explained by the exposure to several caregivingassociated stressors such as worry about the patient, loss of personal time, work absenteeism, multiple roles, and the hospital environment [12]. On the other hand, the administrative employees in the current study had more work-related stressors, which may have reduced the difference. Comparing the current findings to previous data is complicated by the lack of similar local studies and limited international data. A number of international studies showed higher burden, distress, and psychological disorders among caregivers of admitted patients [9- 11]. An Italian longitudinal study of family caregivers of patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness (n = 18) showed a progressive and statistically significant increase of “emotional burden” during the hospital stay [22]. In Netherlands, relatives of ICU survivors could experience strain 3 months after hospital discharge and are at risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder –related features [23]. In a systematic review of psychosocial outcomes in informal caregivers of the critically ill, found that depressive symptoms were the most prevalent in informal caregivers of survivors of intensive care who were ventilated for more than 48 hours and persist at 1 year with a prevalence of 22.8-29.0%, which is comparable with caregivers of patients with dementia [24]. Nevertheless, there is a major difference in the role of the companions in the current study and the companions/sitters in the Western model. For example, the sitters in Western hospitals are typically non-relative trained personnel who have specific caregiving roles to reduce the need and the cost of nursing care among patients with mainly psycho-geriatric conditions [25,26]. On the other hand, the companions in Saudi hospitals are typically family members/friends who provide mainly psychological support to the admitted patients with almost no caregiving role other than helping the patient with eating and walking [3].

The current study showed an interaction between the gender and the study groups with significantly higher stress among the companions that was observed only in males. This interaction was even more apparent in the adjusted model indicating that it is not influenced by gender-specific demographic, clinical, or work-related differences. Interestingly, there were higher stress levels in females compared with males in both the companions and the administrative employees.

Similar to the current findings, gender-specific differences in the level of stress among caregivers have been reported, with more stress reported among females than males [27-30]. This has been partially explained by gender differences in the care recipient’s psychosocial adjustment, with less caregiver’s esteem observed among female caregivers [29]. Additionally, hospital administrative jobs have been shown to be less stressful than clinical jobs and have been used as a control group when examining stress among healthcare workers with caregiving (clinical) responsibilities [13]. A recent review, found the risk factors for caregiver burden to include female sex, low educational attainment, residence with the care recipient, higher number of hours spent caregiving, depression, social isolation, financial stress, and lack of choice in being a caregiver [27]. However, there is a lack of data examining genderspecific differences in the stress levels among hospital administrators as well as a lack of data comparing this in relation to companions.

Exposure to caregiving-associated stress without protective stresscoping strategies may lead to psychological morbidity, poorer quality of life, and a sense of hopelessness [9,27,28]. This may be translated into a significant proportion of companions who require psychological support [9]. Compared with the administrative employees, the companions in the current study adopted more maladaptive stress-coping strategies that were moderately correlated with the level of stress. This may explain the slight increase in the level of stress among these companions. Given the low prevalence of stress management training in the current study, the current findings may highlight the need and the importance of developing psychological interventions to reduce and prevent high stress outcomes among companions [10]. Unfortunately, comparing the current findings is limited by a lack of similar studies that used the same stress-coping tool in a controlled study design. However, in a Korean study to identify attitudes about stress and coping among 33 primary caregivers of Hemodialysis HD patients using Q-methodology, three discrete factors emerged as follows: Factor I (they reduced their stress by participating in religious activities; religious sublimation), Factor II (they always worried about the caregiving situations and about the patients' conditions; nervousness), and Factor III (they thought it better to accept their stressful situations; leading handler). These three factors accounted for 44.5% of all the variance, including Factor I (26.0%), Factor II (10.1%), and Factor III (8.4%) [31].

The current study had many advantages: controlled design; using well-validated tools for perceived stress and stress-coping; and examining pathophysiologic changes. Nevertheless, we acknowledged a number of limitations: the possibility of a reporting bias cannot be excluded because the current study was a self-reported study; the case-control design precluded the detection of any causal associations between potential risks and perceiving high stress levels; and, finally, being a single-center study, the findings should be generalized to Saudi companions with caution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the companions had a slight (marginally significant) increase in the level of stress compared with the administrative employees after adjusting for socio-demographic, clinical, and workrelated characteristics. Females had higher stress levels than males in both of the study groups. Maladaptive stress-coping strategies that were moderately correlated to perceived stress were more frequently used by companions. Companions may need psychological support to reduce and prevent high stress outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the support they received from the SABIC Psychological Health Research and Applications Chair, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, the authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Aiman El-Saed (Asst. Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics) for his assistance in data analysis and writing and Ms. Ahoud Alluhaim for assistance in translation.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Blumenfield M, Milazzo J, Orlowski B (2000) Constant Observation in the General Hospital. Psychosomatics 41: 289-293.

- Worley LL, Kunkel EJ, Gitlin DF, Menefee LA, Conway G (2000) Constant observation practices in the general hospital setting: a national survey. Psychosomatics 41: 301-310.

- Al-Asmary SM, Al-Shehri A-SA, Al-Omari FK, Farahat FM, Al-Otaibi FS (2010) Pattern of use and impact of patient sitters on the quality of healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 31: 688-694.

- Al-Mandeel HM, Almufleh AS, Al-Damri A-JT, Al-Bassam DA, Hajr EA, et al. (2013) Saudi womens acceptance and attitudes towards companion support during labor: should we implement an antenatal awareness program? Ann Saudi Med 33: 28-33.

- Carr FM (2013) The role of sitters in delirium: an update. Can Geriatr J 16: 22-36.

- Figved N, Myhr K-M, Larsen J-P, Aarsland D (2007) Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms. J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry 78: 1097-1102.

- Leiknes I, Tysnes O-B, Aarsland D, Larsen JP (2010) Caregiver distress associated with neuropsychiatric problems in patients with early Parkinson’s disease: the Norwegian ParkWest study. ActaNeurolScand 122: 418-424.

- Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Mitchell AJ, Moreno-García S, Benito-León J (2015) Anxiety and depressive symptoms in caregivers of multiple sclerosis patients: The role of information processing speed impairment. J NeurolSci349:220-225.

- Luchetti L, Porcu N, Dordoni G, Gobbi G, Lorido A (2012) [Burden of caregivers of aged patients at a hospital acute care unit and role of the psychologist in the management of the “fragile” caregiver]. G Ital Med LavErgon 34:A34-A40.

- Nabors LA, Kichler JC, Brassell A, Thakkar S, Bartz J, et al. (2013) Factors related to caregiver state anxiety and coping with a child’s chronic illness. FamSyst Health 31:171-180.

- Klaric M, Franciškovic T, Pernar M, Nemcic Moro I, Milicevic R, et al. (2010) Caregiver Burden and Burnout in Partners of War Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. CollAntropol34:15-21.

- Bialon LN, Coke S (2012) A study on caregiver burden: stressors, challenges, and possible solutions. Am J HospPalliat Care29:210-218.

- Golshiri P, Pourabdian S, Najimi A, Zadeh HM, Hasheminia J (2012) Job stress and its relationship with the level of secretory IgA in saliva: a comparison between nurses working in emergency wards and hospital clerks. J Pak Med Assoc62:S26-S30.

- Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, Varvogli L, Gnardellis C, et al. (2011) Perceived Stress Scale: Reliability and Validity Study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health8:3287-3298.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J Heal SocBehav24: 385-396.

- Cohen S (1988) Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States.

- Carver CS (1997)You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med4:92-100.

- Kasi PM, Naqvi HA, Afghan AK, Khawar T, Khan FH, et al. (2012) Coping styles in patients with anxiety and depression. ISRN Psychiatry2012:128672.

- Ezzati A, Jiang J, Katz MJ, Sliwinski MJ, Zimmerman ME, et al. (2014) Validation of the Perceived Stress Scale in a community sample of older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry29:645-652.

- Katsarou A, Panagiotakos D, Zafeiropoulou A, Vryonis M, Skoularigis I, et al. (2012) Validation of a Greek version of PSS-14; a global measure of perceived stress. Cent Eur J Public Health20:104-109.

- Montel S, Albertini L, Desnuelle C, Spitz E (2012)The impact of active coping strategies on survival in ALS: The first pilot study. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 13: 599-601.

- Moretta P, Estraneo A, De Lucia L, Cardinale V, Loreto V, et al. (2014) A study of the psychological distress in family caregivers of patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness during in-hospital rehabilitation. ClinRehabil28:717-725.

- van den Born–van Zanten SA, Dongelmans DA, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt D, Vink R, van der Schaaf M (2016) Caregiver strain and posttraumatic stress symptoms of informal caregivers of intensive care unit survivors. RehabilPsychol 61:173-178.

- Haines KJ, Denehy L, Skinner EH, Warrillow S, Berney S (2015) Psychosocial outcomes in informal caregivers of the critically ill: a systematic review. Crit Care Med43:1112-1120.

- Boswell DJ, Ramsey J, Smith MA, Wagers B (2001)The cost-effectiveness of a patient-sitter program in an acute care hospital: a test of the impact of sitters on the incidence of falls and patient satisfaction. QualManag Health Care10:10-16.

- Rochefort CM, Ward L, Ritchie JA, Girard N, Tamblyn RM (2012) Patient and nurse staffing characteristics associated with high sitter use costs. J AdvNurs68:1758-1767.

- Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS (2014) Caregiver Burden A Clinical Review.JAMA 311:1052-1060.

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Raschick M (2004) The Relationship Between Care-Recipient Behaviors and Spousal Caregiving Stress. Gerontologist44:318-427.

- Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL (2006) Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psychooncology15:1086-1092.

- Schrank B, Ebert-Vogel A, Amering M, Masel EK, Neubauer M, et al. (2015) Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology.

- Yeun EJ, Bang HY, Kim EJ, Jeon M, Jang ES, et al. (2016) Attitudes toward stress and coping among primary caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis: A Q-methodology study. Hemodial Int.

Copyright: © 2016 Alosaimi FD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.