Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Review - (2023) Volume 12, Issue 6

Towards a Cross-National Analytical Model to Understand Government Perspective and Political Economy

Hassan Hussein*Received: 15-Sep-2023, Manuscript No. JSC-23-23102; Editor assigned: 19-Sep-2023, Pre QC No. JSC-23-23102 (PQ); Reviewed: 02-Oct-2023, QC No. JSC-23-23102; Revised: 09-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. JSC-23-23102 (R); Published: 16-Oct-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2167-0358.23.12.215

Abstract

Doing business in authoritarian contexts could be risky. One reason is the implications of the difference in political, economic, and cultural systems between countries on their political economy. The other is the limited comparative knowledge available on the international political economy as a relatively new sub-discipline within political science and global business since Joan Spero’s poplar introductory textbook in late 1970s. This limitation reflects the much-needed theoretical development within the literature on the Political Economy of Authoritarianism. The paper reviews the literature on political economy and utilizes a few cultural, economic, and political frameworks to offer critical comparative examination on the topic. Drawing on current interdisciplinary theories and combining assessment of national political, economic, and cultural frameworks, a new comparative analytical model is developed. The model generates knowledge to advance our understanding of the political economy of authoritarianism and to examine political economy across nations.

Keywords

Political economy; Authoritarianism, Democracy; Collectivism; Individualism; Economic freedom

Introduction

One of student, who came from an authoritarian context to study in the United States, asked me, “Why do people not protest against the gas price fluctuations over the day in the United States?” The student added, “Even in some European countries, the Yellow Vest Movement was established to protest against government’s decision to slightly increase the gas price.” In her surprise about the uniqueness of the gas price in the United States compared to many other places in her region and elsewhere, she said with amazement, “look at the gas price board here in USA, it’s the biggest thing at all gas stations that you can see from miles away!” A short answer to these questions is the difference in the political economy, which encompasses the relationship between individuals, governments, and public policy [1]. Hassan Hussein also struggled as a novice scholar to grasp a good understanding of what causes the differences between political economies across countries, because empirically, it is impossible to find a significant political system in which the same units perform the same activities simultaneously [2]. However, this answer poses more questions, including what is political economy? How and why they differ? More importantly, what are the implications of economic freedom for individuals and enterprises? Most studies on the interrelationships between measures of political and economic freedom and the political economy have focused on only one aspect, ignoring multilateral relationships [3]. However, the concept of the political economy requires clarification. Thus, Hassan Hussein argues that the literature on political economy requires theoretical development. The existing literature, which has become sophisticated over the years, does not reflect the multidimensional nature of the political economy. The present discussion has primarily a didactic function: to dissect the concept of political economy into its three constituent elements-political, economic, and cultural in an attempt to integrate them into an overall conceptual model for understanding political economy. The following section explores the relevant literature to answer these questions and develop a multidimensional model to help assess and compare political economies across nations. This analytical model introduces an easy-to-use tool to help novice and emerging scholars understand this topic by defining political and economic systems and how they vary across nations, discussing the role culture plays in shaping political and economic systems, and finally introduce a multidimensional model to help understand the differences between political economies across nations, with a focus on the political economy of authoritarianism in the Middle East.

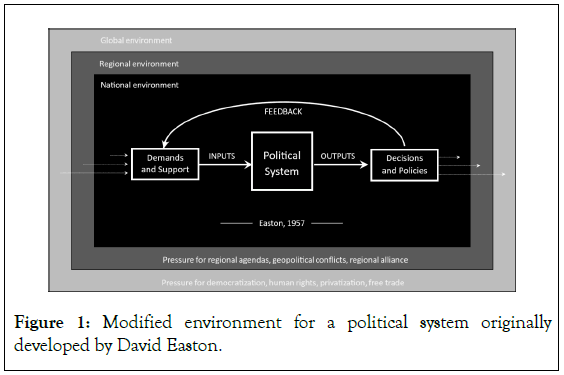

Political System

The political system is a significant component of political economy. Whatsoever the type of political system, such as presidential, parliamentary, or monarchical, a political system is the system of the government of a nation [2]. David Easton contends that a political system comprises three major components: input from the environment, processing, and output to the environment. Inputs are the raw materials that keep the system running, including demand and support. A system without inputs cannot perform any work, and without outputs, we cannot identify the work performed by the system. The outputs represent the finished manufactured products and their decisions. Although these three parts are equally important, Easton argues that public demand and support constitute the inputs that keep the system going; effective systems convert these inputs, by the system’s processes, into outputs (e.g., decisions and policies) for the environment in which the system exists. However, this raises a legitimate question: While all political systems in established democracies or authoritarian regimes are composed of the same three components (inputs, processing, and outputs), how do they differ? This question provides valuable inputs for our attempt assessing political systems. Considering the quality of the input components of a political system, we can draw conclusions about its effectiveness. The quality of inputs can be measured using several determinants, including the level of political freedom, civil rights, socioeconomic status, and power rotation through impartial periodic elections, in line with the standards for free and fair elections [4]. Franz Neumann claims that no political system can fully realize political freedom [5]. Hassan Hussein will elaborate on this later when compare the levels of freedom in democracy and authoritarianism. Although they are closely related, it is important to distinguish between civil and political rights. Civil rights include personal and societal rights. Personal or human rights are inherent in individuals as free and equal beings without boundaries and are enjoyed by citizens, residents, and visitors. However, political rights are derived solely from the state’s political structure [6]. While this may be the case for personal rights in theory, in the Arab authoritarian context, there is a prevailing debate that visitors may enjoy more personal rights than citizens [7]. Furthermore, these rights should be protected by law, as they are valid only if they are institutionalized and enforced by an authorized agency. This applies to all political systems to be effective; even the most democratic system, as argued by Neumann, needs effective safeguards against power abuse or democratic setbacks. The transformation from democracy into dictatorship, as argued by Neumann, could arise when the political system discards its liberal element and reduces the room for freedom available to its members, or ostracizes those with differing opinions [6]. Another way to assess the effectiveness of a political system is to check how demands (inputs) are transformed into political issues. Neumann asserted that demand does not automatically convert into a political issue and may die at birth or linger without support to become a possible political decision. Similar to most systems, the outputs of a political system, such as policies and government attitudes, are determined by its inputs public demand and support. This is important in answering the questions posed earlier by students regarding the noticeable differences among countries. However, without knowing how and why public demand and support vary among countries, we cannot understand the differences between political economies. In the following section, the shapes of public demand and support in different contexts are discussed. Easton stipulates that demand comes from within the system, members of the system, and the external environment. Easton argues that the kind of demand entering a political system from its external environment is shaped by the ecology, economy, culture, personality, social structure, and demography of the country [2]. Although this may be the case in developed sovereign democracies, it is different in authoritarian Arab regimes. In addition to the national environment, Hassan Hussein adds two additional layers to the environment of the political system of authoritarian regimes in the region. Figure 1 depicts the two layers added to Easton’s design to reflect the actual environment of a political system under Arab authoritarianism.

Figure 1: Modified environment for a political system originally developed by David Easton.

The regional environment has direct implications on the kind of demands entering a political system and on its outputs. Factors of the regional environment include political alliance, trade partners, and labor market. For example, the kind of demands entering the political system in Egypt, as one of the authoritarian regimes in the Arab region, may include demand and support from other regional actors and not solely through the national environment such as from the members of the alliance of the war in Yemen [8]. At the same time, member countries of this alliance welcome the labor force from Egypt that contributes to Egypt’s national income [9]. In addition, regional actors (e.g., Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates) have been helping bailout the Egyptian economy in order to receive loans from the International Monetary Fund [10]. Accordingly, the outputs of the political system in Egypt may be personalized in line with these inputs. The outer ring demonstrates factors from the global environment (e.g., world power, IMF, WTO) that may contribute to shaping the inputs and outputs of the political system in Egypt. The major world power actors push for more democratization and greater room for human rights [11]. Furthermore, being in dire financial straits, Egypt has been forced into policy reform by international lenders (e.g., International Monetary Fund). The IMF is forcing Egypt to adopt several policies including consumer-price liberalization, the liberalization of interest rates, exchange-rate liberalization, and privatization [10]. The examples provide non-negligible arguments in favor of considering these two layers when assessing a political system. Finally, the political system of a nation has significant implications on the choice of its economic system. Political systems can be assessed according to two dimensions: collectivism vs. individualism, and democracy vs. authoritarianism. The first dimension assesses the degree to which a country emphasizes collectivism as opposed to individualism. The second dimension assesses the degree to which the country is a democracy or authoritarianism. The following section briefly describes the two dimensions.

Collectivism and Individualism

Recent research has shown that culture is an important determinant of political and economic expectations and preferences, which in turn can have a direct impact on their outcomes [12]. Individualism and collectivism, as the opposite ends of a single cultural dimension, have become the major means of comparison between societies in different comparative disciplines [13]. There is a growing body of literature on collectivism and individualism across disciplines that advances our knowledge on the cultural differences in human behavior and enables us to differentiate among the countries and to compare different collectivistic societies to one another. Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social psychologist and a pioneering scholar who examined cross-cultural groups and organizations and developed the most popular frameworks for measuring cultural dimensions in a global perspective. Collectivism, according to Hofstede, describes a society in which people are integrated into strong cohesive groups that guarantees protection to the members of this society in exchange for unquestioning loyalty [14]. Individualism, on the other end of the spectrum, stands for a society with loose ties between individuals and loosely knit social networks where everyone is expected to look after them and their immediate family only [15].

While collectivistic societies characterized by tight social networks with tendency to hold more common goals, individualistic goals focus primarily on self-interest [15]. Furthermore, recent research has shown that culture is an important determinant of economic expectations, which in turn can have a direct impact on determining the inputs of a political system, as discussed above and accordingly on its economic outcomes and orientation [16].

A plethora of scholarship utilizes the collectivism and individualism framework to explain why some societies focus on the collective nature of social obligation while other focuses on the primacy of the individual [17]. Although cultural homogeneity within a single country does not often exist because human behavior and culture are complex, the framework is widely used to categorize countries as collectivistic or individualistic. Alessandro Germani and others conducted empirical studies to validate the framework in Italy and provided evidence that the framework is a reliable and valid instrument to assess individuals’ individualism and collectivism on a country level [12]. In contrast, despite the popularity and the widespread reliance on the collectivism and individualism cultural framework, some argue that mapping societies along the axes of a single dimension of collectivism or individualism is not enough where researchers must aim to capture the complexities of human behavior and understand its interaction with the larger socioecological context [18]. There is a relationship between collectivism and the political and economic systems of a country. On the one hand, members of a collectivistic society identify themselves as members of a group to which they belong, and they are more likely to adopt the group’s goals and values [19]. Dominant collectivistic societies, as such, tend to lean towards political and economic systems that promote the group interests rather than the individual interest [20]. Eastern Asian societies and European social democracies are good example [21]. On the other hand, high individualism represents the degree to which people in a country prefer to act as individuals rather than as members of groups [22]. Individualistic societies that advance the individual interests over the group interest prefer more liberal economic and political systems e.g., the United States [19]. In addition, Cambridge research examined the role of individualistic values in promoting economic development and found a relationship between individualistic personal attitudes and reporting corruption [23].

Economic System

There are three types of economic system around the world: market economy, command economy, and mixed economy [24]. In a market-oriented economy, also known as capitalism or free market, economic decisions and the pricing of goods and services are made through the interactions of individual citizens and businesses and mainly driven by the law of supply and demand [25]. Government intervention in the free-market economy is limited to the governance aspects to ensure equality for all citizens. In contrast, a command economy is fully controlled by the government where the government is the central planner who decides which goods and services to produce, the production and distribution method, and the prices of goods and services [26]. Command economy is common among authoritarian regimes where there is no competition rather monopolies, which are owned by the government [25]. A result from government restrictions on producing several products and services, a black economy arises to fulfill the needs not met by the government [27]. Accordingly, the activities of such black economy are not taxed because they take place illegally away from government control; and this may contribute to weaken authoritarian government by drying up its sources of income [25]. The phenomenon of black economy is also common in most Arab economies both in wealthy and developing economies. While governments may restrict the production and distribution of non-essential products and services in developing economies as part of their austerity policies, wealthy Arab economies also intervene to restrict products and services that do not align with the dominant religious beliefs and societal norms [28]. This may also extend to some essential commodities such as the ban on the sell and distribution of red meat in Egypt for one month by the former president Anwar Sadat [29]. A mixed economy is partly run by the government and partly as a free market economy where economic decisions and the pricing of goods and services are driven by the law of supply and demand [30]. Most world economies are defined as mixed economy where democracies lean to the free- market side with growing privatization while authoritarian regimes lean more towards the command economy and control most of the economic decisions with very little left to the private sector [31]. Despite the waves of democratization and economic liberalization caused by globalization or forced by international lenders such as the International Monetary Fund, the Middle East and North Africa region was an exception. Christian Neugebauer argues that authoritarian regimes in the region rejected the economic liberalization believing it would strengthen the bourgeoisie middle class which could potentially develop into a democratizing force [32].

Understanding Political Economy across Nations

The above discussion shows the indisputable fact that several factors constitute a political economy. To understand the difference between political economies across nations we must consider these factors. In addition to the political and economic landscape, culture is an important determinant of political and economic expectations and preferences, which in turn can have a direct impact on the orientation and outcomes of political and economic systems of a country [2]. Utilizing the annual global Democracy Index by the Economist and the Hofstede six-dimensional culture model, the analytical model provides clear comparative understanding of the political economy across nations.

To highlight cultural differences between the countries, this analytical model utilizes numerical data from the work of Hofstede comparing attitudes and values between countries. On a scale of 1 to 100, the individualism indicator measures the degree to which people in a country prefer to act as individuals or as a group. A score of 100 means more individualistic society where people act individually with self-image, and a score of 1 means more collectivistic society where people act collectively as a group with self-image defined in terms of “we” [33]. The Democracy Index provides an annual snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide. The Democracy Index is based on five categories: Electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. Based on its scores on a range of indicators within these categories, each country is then classified on a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 means “full democracy”, and 1 means “authoritarian regime”. Table 1 below presents national scores for individualism and democracy dimensions as extracted from the Hofstede database and from the 2022 Democracy Index for a sample of ten countries representing different regions: China, Greece, Iraq, Japan, Kuwait, New Zealand, Portugal, Qatar, the United States of America, and Venezuela [34,35].

| Dimensions | Individualism (out of 100) | Democracy (out of 10) |

|---|---|---|

| China | 20 | 1.94 |

| Greece | 35 | 7.97 |

| Iraq | 31 | 3.13 |

| Japan | 46 | 8.33 |

| Kuwait | 25 | 3.83 |

| New Zealand | 79 | 9.61 |

| Portugal | 27 | 7.95 |

| Qatar | 25 | 3.65 |

| United States | 91 | 7.85 |

| Venezuela | 12 | 2.23 |

Table 1: Numeric scores for individualism and democracy extracted from the Hofstede database and from the annual Democracy Index by the Economist.

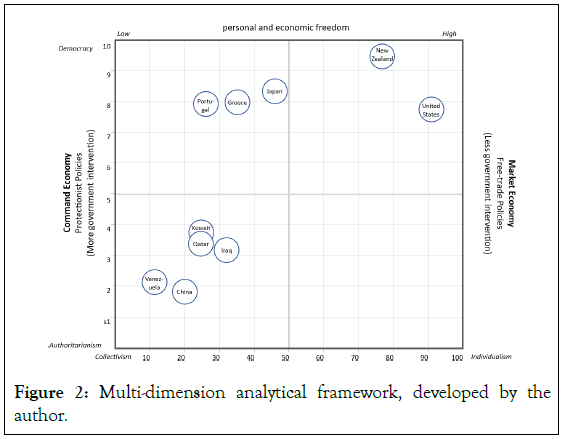

Cultural difference between countries is reflected in Hofstede’s dimension of “Individualism”, and the level of democracy among countries is reflected in the Democracy Index country score. By plotting the indicators of the level of democracy from the Democracy Index and level of individualism from the Hofstede culture model for the ten countries on the analytical model in Figure 2, below, we can reveal the differences between the countries. On X and Y axis, the X axis represents the level of individualism vs. collectivism as extracted from the Hofstede culture model for the ten countries. The Y axis represents the level of democracy vs. authoritarianism as extracted from the 2022 Democracy Index for the ten countries.

Figure 2: Multi-dimension analytical framework, developed by the author.

At the two ends of the spectrum, we find the United States of America with the highest score of individualism of 91 and democracy score of 7.85, and Venezuela with individualism score of 12 and democracy score of 2.23. These scores put the USA in the upper right corner of the model as an individualistic market economy with free trade orientation. On the other hand Venezuela in the lower left corner of the model as an authoritarian economy with protectionism orientation. Comparing the US and Portugal, with individualism score of 27 and democracy score of 7.95, Portugal is in the upper left corner of the model as a social democracy with less free trade orientation compared to the US. Although Portugal scores higher than the USA in the democracy level, it leans more towards protectionism policies with less room for individual’s economic freedom compared to the United States of America, and this applies to Greece and Japan who also plotted on the upper left corner of the model. This indicates that the democracy level alone is not enough to understand the political economy of a country. The multidimensionality perspective suggests that the higher level of collectivism in these three countries shapes the kind of inputs to their political system, as discussed earlier, and accordingly determines its outputs of economic policies and market orientation. In addition, if we consider another dimension from the Hofstede culture model (i.e., uncertainty avoidance) we can understand why Greece, Japan, and Portugal lean towards more protectionist policies compared to the US even though these three countries score higher on democracy level than the USA. The uncertainty avoidance dimension measures the degree to which the members of a society fear ambiguity and the unknown future [36]. On a scale of 1 to 100, the uncertainty avoidance dimension measures how different nations interpret the unknown and deal with unpredictability. A score of 100 indicates that society encourages measures to regulate actions to rule out ambiguity and avoid situations of uncertainty. On the other hand, a society with low score of uncertainty avoidance embraces deviation or new approaches and members of this society are encouraged to experiment and test [36]. The uncertainty avoidance scores for Greece, Japan, and Portugal are 100, 90, and 99 respectively [34]. The high fear of change as such shapes the kind of demands entering the political system from its environment in these three countries, then transformed into outputs if form of economic policies and economic orientation. Moving to the lower left corner of the model, we can see China with individualism score of 20 and democracy score of 1.94; Iraq with individualism score of 31 and democracy score of 3.13; Kuwait with individualism score of 25 and democracy score of 3.83; and Qatar with individualism score of 25 and democracy score of 3.65 where the three of them along with China and Venezuela are among authoritarian regimes with mixed economy that leans more towards a command economy [34]. Governments in such side of the model adopt more protectionist economic policies and take responsibility for the provision of goods and services [37]. Looking at the government intervention in the provision of goods and services for all the five authoritarian countries in the lower left corner of the model, we can see that many goods and services are provided by the state. If we consider airlines as an example of transportation service in the five countries in the authoritarian side of the model, we find that this service is strictly owned and provided by the government through state-owned enterprise [38]. The three Arab countries (Iraq, Kuwait, and Qatar) in the authoritarianism side of the model also score high on the uncertainty avoidance dimension with a score of 96, 80, and 80 respectively [34]. The high level of uncertainty avoidance may reflect the fear of change and the unknown (e.g., economic liberalization and democratization). Fear, from one hand, as argued by Neumann, is what makes and sustains authoritarianism [5]. On the other hand, anti-neoliberalism and protectionism fosters the power of material distribution of authoritarian regimes and increasing their sources of income (e.g., tariffs, taxes, price manipulation, and state-owned enterprises) [32]. At the same time, economic liberalization could pose a threat for authoritarian regimes as it has potentials to increase the economic and political power of private actors that could developed into a democratizing force [32]. Furthermore, economic liberalization could also help stabilize authoritarian regimes such as the positive impact on poverty from the interest rates and exchange-rate liberalization, and the role of consumer-price liberalization in Egypt during the mid-late 1990s as a quid pro quo for emergency lending by international lenders [32]. Yet, the political economy of authoritarianism is stagnant and the response to the pressure for more economic liberalization (e.g., privatization) is a mere rotation between the government and the elite members of the regime as a regime survival technique [39]. Furthermore, governments in the collectivistic left side of the model, either authoritarian or democratic regimes, play varying role in deciding which goods and services to produce, the production and distribution method, and the price of goods and services. This corresponds to the questions raised earlier student about the difference she realized between the collectivistic society both in the authoritarian Arab regimes and the European social democracies compared to the United States of America. The noticeable big signboard for the gas price in the US reflects the nature of the economic system in a more individualistic society where price of goods and services is determined by the law of supply and demand where gas price varies between gas stations and fluctuates during the day. In contrast, gas price in more collectivistic regimes in social democracies and authoritarian regimes is determined by the government as the central planner. This interprets the manifested difference in the size of price board for gas in United States of America compared to other collectivistic contexts as noticed by my student earlier. On the one hand, in more collectivistic societies the government sets a nationwide price for gas and customers, therefore, may not need a billboard to know the price. On the other hand, the price is competitive and set by individual gas stations in a free market, and therefore a big price board is well justified. This also corresponds to her question about the reason of the establishment Yellow Vest Movement in France that was triggered after the decision of the head of the state, President Emmanuel Macron, to slightly increase gas price. In addition to the difference in the significance of gas prices between nations, the political economy of a country can also be manifested in different facets of its daily life. Another example is education as the source for one of the four building blocks of an economy that is used to produce goods and services. In the Arab authoritarianism the amount and types of skilled and educated force needed by the labor market is centrally determined by government through its central admission coordination bureau of universities and higher institutes [40]. Field of study, as an individual right, is determined by government orientation and through its central admission coordination bureau on a score-based system using the average of grades in the General Secondary Education Certificate (GSEC) in most Arab authoritarian regimes [40]. This became a great source of concern for students and their families where the fear of results drives some of the students to suicide. Such social pressures to get high scores have created opportunities to cheat, leaking of exams questions and selling those [40]. This is not only contributing to weakening the quality of public education but also reducing the level of freedom for individuals in Authoritarian Arab regimes and quality of labor force entering the market [41]. Finally, the above discussion and the analytical multi-dimension model attempt to contribute to the ongoing discussion on the differences of political economy across nations. Users of the model may decide to find national indicators on democracy and individualism from other sources than the Democracy Index and the Hofstede culture model and apply them to the comparative model the same way. More interdisciplinary empirical research is recommended to help validate the findings.

Conclusion

Recent research has shown that culture is an important determinant of economic expectations and preferences, which in turn can have a direct impact on economic outcomes. Culture shapes political system, a political system then determines the type of economic system based on the inputs from the environment, and the three of them constitute the political economy of a country that is defined as a branch of social sciences that focuses on relationships between individuals, governments, and public policy. Culture, therefore, is an indispensable requirement for understanding political economy. This review contributes to a small literature trying to establish the micro-level mechanisms through which cultural values can lead to better understanding of the national differences in the global political economy. The purpose of the paper was to establish a reliable and easy-to-use measurement tool for understanding the political economy across nations. The paper combined multidimensional perspectives to help understand the relationships between the constituents of political economy: Individuals, government, and policies. The proposed analytical model is indicator driven rather than theory driven. As the global economy is becoming more volatile to endless global events such as the global financial crises, the new coronavirus pandemic, and the war in Ukraine, the model has simply expanded as a response to provide more interactive and up-to-date analysis. Furthermore, the model responds to the dynamic nature of global orientation on protectionism and free market as manifested in several recent developments such as the rise of more conservatism around the globe and Brexit. The model demonstrates the indispensable role of culture in examining and understanding the nature of political economy across nations. The higher the individualism level of a country the less the government intervention where people have more economic freedom compared to authoritarianism. The higher the collectivism level of a country the higher the government intervention where people have less economic freedom compared to democracy. Finally, the model introduces a useful didactic tool to understand political economy across nations. Future empirical research is recommended to help validate the findings from interdisciplinary perspectives.

Limitations and Future Research

The preceding results have limitations. Given the nature and sensitivity of the topic in the Middle East Region, consecutive national data is limited especially among authoritarian countries. Cross national validation is also a limitation. Furthermore, the term authoritarianism has negative connotation when translated into Arabic. The goal of the study has been to provide indicator-based tool for interdisciplinary emerging scholars interested in exploring the myriad challenges facing democracy. Hassan Hussein expect this indicator-based to be useful for cross-national comparison among countries in the region and across regions. Future interdisciplinary empirical research is recommended to better validate the findings from different perspective.

References

- Chelwa G, Hamilton D, Green A. Identity group stratification, political economy and inclusive economic rights. Dædalus. 2023;152(1):154-167.

- Easton D. An approach to the analysis of political systems. World politics. 1957; 9(3):383-400.

- Jordaan JA. Economic freedom, post materialism and economic growth. Soc Sci and humanit. 2023;7(1):100416.

- Norris P. Why electoral integrity matters. Cambridge University Press.2014.

- Neumann FL. The concept of political freedom. Columbia Law Review. 1953;53(7):901-935.

- Gavison R. On the relationships between civil and political rights, and social and economic rights. The globalization of human rights. 2003:23-55.

- Parolin GP. Citizenship in the Arab world: kin, religion and nation-state. Amsterdam University Press. 2009.

- Parveen A. The yemen conflict: Domestic and regional dynamics. West Asia in Transition, II. 2019;1(4):130-148.

- Schielke S. Migrant dreams: Egyptian workers in the Gulf States. American University in Cairo Press. 2020.

- Sons S, Wiese I. The Engagement of Arab Gulf States in Egypt and Tunisia since 2011: Rationale and Impact. 2015.

- Balfour R. Human rights and democracy in Europe foreign policy: The cases of Ukraine and Egypt. Routledge. 2013.

- Germani A, Delvecchio E, Li JB, Mazzeschi C. The horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism scale: Early evidence on validation in an Italian sample. J Child Fam Stud. 2020; 29: 904-911.

- Gouveia VV, Clemente M, Espinosa P. The horizontal and vertical attributes of individualism and collectivism in a Spanish population. The J Soc Psychol. 2003; 143(1):43-63.

- Hofstede G. National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International studies of management and organization. 1983; 13(1-2):46-74.

- Hofstede G. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York. 2010.

- Jhally S. The political economy of culture. In cultural politics in contemporary America. Routledge.2022:65-81.

- Kim UE, Triandis HC, Kagitcibasi CE, Choi SC, Yoon GE. Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications. Sage Publications, Inc.1994.

- Voronov M, Singer JA. The myth of individualism-collectivism: A critical review. The J Soc Psychol. 2002; 142(4):461-480.

- Shulruf B, Hattie J, Dixon R. Development of a new measurement tool for individualism and collectivism. J Educ Psychol. 2007;25(4):385-401.

- Suh EM, Lee H. Collectivistic cultures. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. 2020:763-765.

- Soh S, Leong FT. Validity of vertical and horizontal individualism and collectivism in Singapore: Relationships with values and interests. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2002;33(1):3-15.

- Chiou JS. Horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism among college students in the United States, Taiwan, and Argentina. The J Soc Psychol. 2001;141(5):667-678.

- Amini C, Douarin E, Hinks T. Individualism and attitudes towards reporting corruption: Evidence from post-communist economies. J Institutional Econ. 2022;18(1):85-100..

- Zimbalist A, Sherman HJ. Comparing economic systems: a political-economic approach. Academic Press. 2014.

- Harcourt GC. Capitalism, Socialism and Post-Keynesianism. Books. 1995.

- Foa RS. Modernization and authoritarianism. J Democr. 2018;29(3):129-140.

- Kim DS, Moon C. Authoritarian legislature, legitimacy strategy, and shadow economy. Democratization. 2022; 29(6):1077-1096.

- Bazoobandi S. Political Economy of the Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds: A Case Study of Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Routledge.2012.

- Kirk JB. Egypt during the Sadat Years. 2001.

- Ken Farr W, Lord RA, Wolfenbarger JL. Economic freedom, political freedom, and economic well-being: a causality analysis. Cato J. 1998;18:247.

- Mendoza EG, Quadrini V. Unstable prosperity: How globalization made the world economy more volatile. National Bureau of Economic Research.2023.

- Neugebauer C. Economic Liberalization and Authoritarianism. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.2022.

- Trendowski J, Trendowski S, Karaatli G, Stuck J. Cross-Cultural Inclusion: Chinese Students in the American Classroom. The J Int Bus Res. 2022:29.

- Hofstede G. The Hofstede Center. 2023.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. Democracy index 2022: frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine. 2022.

- Hofstede G. National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. Int Stud Manag Organ.1983;13(1-2):46-74.

- Carney RW. Authoritarian capitalism: Sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises in East Asia and beyond. Cambridge University Press.2018.

- Huang J, Tsai KS. Securing authoritarian capitalism in the digital age: The political economy of surveillance in China. The China J. 2022;88(1):2-8.

- Albrecht H, Schlumberger O. “Waiting for Godot”: Regime change without democratization in the Middle East. Int Political Sci Rev. 2004;25(4):371-392.

[Crossref]

- Hammoud R. Admission policies and procedures in Arab universities. Towards an Arab higher education space: International challenges and societal responsibilities. 2010 Dec 31:69.

- Schlumberger O. Debating Arab authoritarianism: Dynamics and durability in nondemocratic regimes. Stanford University Press. 2007.

Citation: Hussein H (2023) Towards a Cross-National Analytical Model to Understand Government Perspective and Political Economy. J Socialomics. 12:215.

Copyright: © 2023 Hussein H. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.