Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

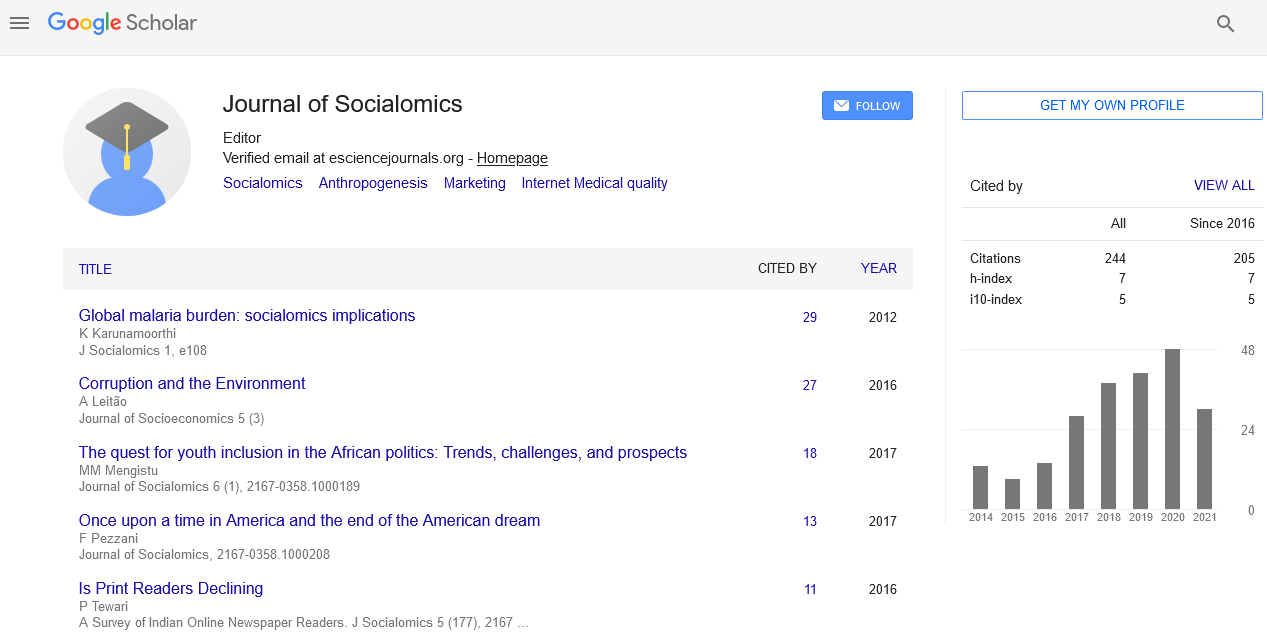

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Opinion Article - (2025) Volume 14, Issue 2

Street-Level Bureaucracy and Public Trust in Low-Income Communities

Ahmed El-Sayed*Received: 26-May-2025, Manuscript No. JSC-25-29732; Editor assigned: 28-May-2025, Pre QC No. JSC-25-29732; Reviewed: 11-Jun-2025, QC No. JSC-25-29732; Revised: 18-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. JSC-25-29732; Published: 25-Jun-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2167-0358.25.14.271

Description

In many urban settings, the relationship between citizens and state institutions is shaped not by official policies but through day-to-day encounters with low-ranking public employees. These individuals, known as street-level bureaucrats, include social workers, clerks, police officers, and local administrators. They represent the most immediate and frequent point of contact between the state and the public, especially in low-income neighborhoods. While their duties may seem routine, their influence over how services are delivered and perceived is considerable.

Citizens living in underserved communities often interact with public institutions through long lines, rigid forms, or sudden requests for documentation. The procedures may appear neutral, but they often feel burdensome and opaque. In these settings, the behavior of the individual behind the counter can matter more than the policy being implemented. A helpful official who explains a form, bends a rule slightly, or simply listens with patience can make a significant difference in how a citizen interprets the institution as a whole. Likewise, dismissive or hostile treatment can create a lasting sense of alienation or resentment.

Street-level workers operate under constraints that influence how they perform their duties. High caseloads, limited training, and bureaucratic inefficiencies force them to make daily decisions that go beyond written guidelines. These judgments who gets served first, who receives leniency, who is referred to another office accumulate to shape access to rights and services. In lowincome areas, where dependence on public support is high, these decisions are not merely technical. They affect food security, housing stability, and access to education. The discretion used in these cases can become a source of inequality if applied inconsistently or without oversight.

Many of these workers also live in the communities they serve. This dual role as both enforcer and neighbor adds complexity to their actions. In some cases, familiarity builds trust and improves communication. In others, it creates tension, especially when decisions appear to favor one group over another. Allegations of favoritism or bias can erode confidence in the fairness of public service delivery. At the same time, the closeness of these relationships can serve as a buffer against complete institutional distrust, offering a more human dimension to government processes.

Public trust in institutions often depends less on national discourse and more on these everyday interactions. While political debates and large-scale reforms may shape broad opinions, individual experiences with frontline workers determine how people navigate systems and whether they believe those systems work in their favor. In environments where institutional failure is a common memory, street-level decisions carry even more weight. A denied application or unexplained delay may reinforce a long-held view that public systems are designed to exclude rather than support.

There is also a psychological toll on the workers themselves. Tasked with implementing policies they may not fully agree with, or facing pressure to meet performance targets under poor working conditions, many feel stress, frustration, or helplessness. Some develop coping mechanisms such as emotional detachment, strict rule enforcement, or symbolic gestures of assistance. Others find meaning in their work through moments of impact or community recognition. Understanding their perspective is important not to excuse poor behavior, but to design better systems that reduce conflict between personal judgment and professional expectations.

Conclusion

Efforts to improve public trust must therefore look beyond procedural reforms and consider the social environment in which public service occurs. Community-based feedback, local forums, and participatory planning can help bridge the divide between policy intent and everyday delivery. When residents are able to share their experiences and propose adjustments, services become more responsive and equitable. However, these efforts require political will and sustained attention to avoid becoming symbolic gestures with little follow-through.

Citation: Sayed A (2025). Street-Level Bureaucracy and Public Trust in Low-Income Communities. J Socialomics. 14:271.

Copyright: © 2025 Sayed A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited