Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- CiteFactor

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture (AGORA)

- Electronic Journals Library

- Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI)

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Scholarsteer

- SWB online catalog

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2019) Volume 10, Issue 3

Screening Desi and Kabuli Chick Pea Varieties against Fusarium Wilt Resistance in West Gojam, Northwestern Ethiopia

Awoke Ayana1, Negash Hailu2* and Wondimeneh Taye32Department of Plant Science, Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

3Department of Plant Science, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia

Received: 22-Jan-2019 Published: 28-Feb-2019

Abstract

Ethiopia is the largest producer of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) in Africa. A number of abiotic and biotic factors are responsible for its yield gaps of being below its’ potential. One of the greatest biotic stress reducing potential yields of chickpea is Fusarium wilt, Twenty-one chickpea varieties from Desi and Kabuli type were screened against Fusarium wilt resistance at Adet Agricultural research center naturally on the field condition and artificially in screen house. The design used on this experiment was randomized complete block design (RCBD) on field condition with three replications and completely randomized design(CRD) inside screen house with three replications to identify the best resistant Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties against Fusarium wilt of chickpea on field and to study the aggressiveness of the pathogen. The Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties showed significant variation in all tested disease and crop parameters. From Desi varieties, the highest percentage of incidence (73%) was recorded from the variety Dube and three were moderately resistant, two were susceptible and six were highly susceptible. From Kabuli chickpea varieties, the highest percentage of incidence (68%) was recorded from the variety Habru and one variety (Dehera) was resistant, four were moderately resistant and five were highly susceptible. There were no highly resistant chickpea varieties from Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties. Therefore, breeders should develop highly resistant chickpea varieties for Fusarium wilt of chickpea.

Keywords

Botanicals; Chickpea; Desi; Kabuli; Fusarium wilt; Resistance; Screening

Introduction

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) is the second most important food legume crop after common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and third in production worldwide [1-3]. Ethiopia shares 2% among the most chickpea producing countries next to India (73.3%), Turkey (8%) and Pakistan (7.3%) [4]. Ethiopia is the largest producer of chickpea in Africa accounting for about 46% of the continent’s production during 1994-2008 [5,6]. About 85% of Ethiopian chickpea production is predominated by Desi type chickpea [7]. However, recently there has been an increase in the interest of farmers in growing large seeded Kabuli varieties due to their higher price in the market [8]. The two types represent different genetic background in disease resistance and important agronomic traits, such as cold tolerance and growth habit [9].

In Ethiopia, chickpea is grown in Woina Dega (midlands to high altitude between 1500 and 2600 m above mean sea level) agro-ecologies with a rainfall of 700–1300 mm [5,10]. Chickpea is a less labor-intensive crop and its production demands low external inputs compared to cereals [11]. It is an important source of protein for human food and animal feed [12,13]. It supplies protein to the poor and thus known as poor man’s meat. In Ethiopia, Chickpea seed can be eaten as green vegetable (eshet),split seeds (‘kik’), roasted (kollo), boiled (nifro) and grounded seeds (shiro wot) [14]. Chickpea returns significant amount nitrogen to soil fertility and breaking the disease cycles of important cereal [15,16].

Despite of its importance for food security and soil fertility, an average chickpea yield in Ethiopia is usually below 2.8 ton ha-1 although its’ potential yield is more than 5.6 ton ha- 1 [7]. A number of abiotic and biotic factors are responsible for its yield gaps. This is resulted from cultivation of susceptible varieties to disease, limited awareness and access of farmers to seeds of new crop varieties, low genetic diversity of cultivated chickpea, little protection against Weeds, Insect pests and Nematodes [17-19].

One of the greatest biotic stress reducing potential yields of chickpea on rain-fed Agriculture is chickpea wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp ciceris [20]. It is one of the major soil borne disease of chickpea worldwide [21]. The disease is more prevalent in most areas of north western and central Ethiopia [4,10]. Wilt disease is a major chickpea production constraint causing yield losses by reducing the number of plants. Yield losses vary 10% to 100% depending on varietal susceptibility and agro climatic conditions [22].

Different management methods of Fusarium wilt of chickpea are recognised by Merkuz and Getachew [18] reported that raised bed preparation, tolerant variety and optimum time of planting prevented the wilt incidence and reduce mortality of wilt [23-25]. Landa et al. [26] reported that integrated management of Fusarium wilt of chickpea with sowing date, host resistance and biological control and conclude sowing date has greatest effect on incidence of Fusarium wilt and yield of chickpea.

The development of resistant varieties is the most effective method to manage Fusarium wilt and contribute to stabilizing chickpea yield gap. Host resistance is the main component of integrated disease management and most efficient, cheapest, environmentally safe and economical way of managing fusarium wilt of chickpea [27-31]. Identifying resistant chickpea varieties against fusarium wilt is an important solution to optimize the yield gap on chickpea production. Therefore, the objectives of this study were: to screen the resistance of Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties against Fusarium wilt of chick pea on naturally infested field and by artificial inoculation of the pathogen in screen house.

Materials and Methods

Description of the study area

The experiment was conducted on field and in screen house condition at Adet Agricultural research center in 2017 main cropping season. The area is found at 553km far from Addis Ababa. The experimental site is located 11°17’N latitude, 37°43’E longitude and 2240 m.a.s.l [18]. The area receives average annual rain fall of 1284 mm. The average daily minimum and maximum temperature is 16.8°C and 23.5°C respectively. The soil type of the area is verity soil. The area is selected because of its suitable condition for chickpea production and higher prevalence of Fusarium wilt of chickpea [10].

Experimental treatments

A total of twenty-one (21) varieties; Eleven(11) Desi type including local cheek and susceptible check, 10 Kabuli type with standard cheek was evaluated for Fusarium wilt of chick pea on field condition. Standard cheek is a variety known for its resistance for Fusarium wilt disease where as local check is a variety mostly cultivated by farmers in the study area. The varieties were obtained from Debre Zeit agricultural research center and selected based on altitude range of Ethiopia for chickpea cultivation. The varieties year of release, source, seed colour, type of chickpea and altitude range for adaptation is described in Table 1 below. In screen house experiment five highly susceptible varieties (Dube, Yelbie, Marye, Dimtu and one control, Areti) were selected on field and inoculated by three level of inoculum concentration of the pathogen.

| No. | Variety/Acc. No | Year of release | Seed color | Chickpea type | Altitude (m.a.s.l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dube | 1978 | Grey | Desi | 1600-2000 |

| 2 | Maye | 1985 | Brown | Desi | 1900-2600 |

| 3 | Worku (DZ-10-16-2) | 1994 | Golden | Desi | 1900-2600 |

| 4 | Akaki (DZ-10-9-2) | 1995 | Golden | Desi | 1900-2600 |

| 5 | Kutaye (ICCV-92033) | 2005 | Red | Desi | 750-1900 |

| 6 | Fetenech (ICCV-92069) | 2006 | Reddish | Desi | 750-1900 |

| 7 | Natoli (ICCX910112-6) | 2007 | Light Golden | Desi | 1800-2700 |

| 8 | Minjar | 2010 | Golden | Desi | 1800-2600 |

| 9 | DIMTU | 2016 | Golden | Desi | 1600-2400 |

| 10 | D-Z-10-4 | 1974 | White | Kabuli | 1600-2300 |

| 11 | Areti (FLIP 89-84c) | 1999 | White | Kabuli | 1800-2600 |

| 12 | Habru (FLIP-88-42c) | 2004 | White | Kabuli | 1800-2600 |

| 13 | Ejeri (FLIP-97-263c) | 2005 | White | Kabuli | 1800-2600 |

| 14 | Tji (FLIP-97-266c) | 2005 | White | Kabuli | 1800-2700 |

| 15 | Yelbe (ICCV-14808) | 2006 | Yellowish | Kabuli | 750-1900 |

| 16 | ACOSE DUBE/Monino | 2009 | Whit cream | Kabuli | 1800-2400 |

| 17 | DHERA | 2016 | White | Kabuli | 1600-2400 |

| 18 | HORA | 2016 | White | Kabuli | 1600-2400 |

| 19 | Shasho (Standard check) | 1999 | White | Kabuli | 1900-2600 |

| 20 | D-Z-10-11 (susceptible check) | 1974 | Light brown | Desi | 1800-2300 |

| 21 | Adet local (Local Check) | -- | Reddish | Desi | -- |

Source 29. MoARD

Table 1: Description chickpea varieties evaluated in the field experiment.

Experimental design and procedure

Field experiment: The field experiment was arranged in randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications. The size of a single plot was 3 m2 (2 m × 1.5 m). The inter-row, intrarow, between plots and blocks spacing was 0.3 m, 0.1 m, 0.5 m and 1 m, respectively. A single plot was planted by five rows each containing twenty (20) plants. Phosphorous fertilizer (30 g DAP per plot) was applied once during planting based on the recommendation. Weeding was done three times at seedling, flowering and podding stage.

Screen house experiment: Screen house experiment was arranged in completely randomized design (CRD) with three replications using 20 cm diameter plastic pots. The soil was autoclaved before filled in pots. Then Pots were filled by mixing 2 kg black soil and 0.5 kg sand soil after moistening the mixture with water. Four susceptible chickpeas and one control variety from the experimental field were identified. Then 10 surface sterilized seeds per pot were sown from each variety and watering was done regularly.

Identification of the pathogen: Infected chickpea roots showing symptoms of the disease was obtained from the experimental field and taken to the laboratory. The roots were cut into small sections (0.5 cm), washed thoroughly with tap water and surface sterilized with 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 minutes. Then sections were rinsed three times in sterilized distilled water and dried on sterilized filter papers. Potato dextrose agar was added in five petridishes having 9 cm diameter. Then sterilized root sections were plated at the rate of five (5) sections per plate. Then Petri plates were incubated at 25°C for 7 days [32]. New petri dishes containing PDA were prepared. Seven-dayold cultured spores were sub-cultured to new petri plates. Then pure cultured pathogen was observed through microscope and identified by comparing with the morphological characters of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris described by Van der Maesen [33]. After the spores per ml of culture suspension was conted using haemocytometer, and adjusted to be 104-105 spores per ml, different concentrations of spore suspensions were inoculated.

Inoculum preparation and soil inoculation: The inoculum was prepared from the pure cultured pathogen. Ten ml of distilled water was added from the suspension of each petri plates and the suspension was washed using loops. Then the suspension was strained with double muslin cloth and collected in a sterilized glass beaker. Finally, beakers were placed in side-sterilized incubator until use. Pots were watered one day before inoculation of spore concentration to create suitable condition for establishment of the disease. Finally, 5 ml, 10 ml and 15 ml of conidial suspension from the incubator beaker was inoculated to each pot after 25 days after sowing by drenching method [34,35]. Hand syringe was used for inoculation. The inoculated pots were drenched by distilled water and used as control.

Data collection

Disease data

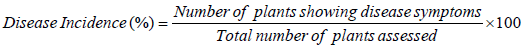

Disease incidence (%): Was recorded as proportion of plants showing wilt symptom out of the total plants per plot and per pot both at seedling and reproductive or lowering stage.

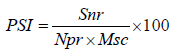

Disease severity (%): Were recorded for four consecutive weeks after occurrence of the disease from ten randomly selected and pretagged plants on field experiment and for three consecutive weeks from five plants in screen house experiment using 1-9 severity scales; where 1=No visible symptoms; 2=minute yellowing discoloration prominent on the apical leaves; 3=yellowing discoloration on 5-10 leaves and slight drooping of apical leaves; 4=wilting of a single branch and clear drooping of apical leaves; 5=defoliation initiated, breaking and drying of two branches slight to moderate; 6=defoliation, broken, dry branches common, some plants killed; 7=defoliation, broken, dry branches very common, up to 25% of a plant parts killed; 8=defoliation, broken, dry branches very common, 50% of a plant parts killed; 9=a plant totally killed [15,36-39] and scales were converted to percentage of severity index (PSI) using the following formula.

Where, Snr is the sum of numerical ratings, Npr is number of plant rated; Msc is the maximum score of the scale. Means of the severity recorded for four consecutive years were used for data analysis.

Data analysis

The disease incidence and severity, phonological and yield parameters data were analyzed statistically with analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS version 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., USA) following the standard procedure given by Gomez and Gomez [40]. Whenever treatment differences were significant, Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) was used to separate differences among the treatments means at 5% probability level. Correlation analysis was done to know the association of disease incidence with severity and phonological with yield related parameters.

Results and Discussion

Incidence of Fusarium Wilt

The disease incidence result of field experiment reveals that there was highly significant difference at (p<0.01) among the screened Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties. The highest percentage of disease incidence (73%) was recorded from the variety Dube while the lowest incidence (27%) was recorded from the variety Worku from the Desi type chickpea. From those varieties Dube, D-Z-10-11, Marye, Minjar, Natoli and Dimtu were highly susceptible and Adet local and Kutaye were susceptible and Fetenech was moderately resistant (tolerant). The overall mean of percentage of disease incidence of Desi chickpea varieties was 46.7% (Table 2). Chaudhry et al. [16] also screened one hundred and ninety-six chickpea germplasm lines/cultivars for resistance to wilt disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri in a wilt sick plot.

| No. | Chickpea varieties (Desi type) |

Incidence (%) | Percentage Severity index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st week | 2nd week | 3rd week | 4th week | |||

| 1 | DZ-10-11 | 66.67abc | 21.12cdefgh | 26.27def | 36.67abcd | 44.07abc |

| 2 | Dube | 73a | 28.87ab | 35.18abc | 38.51abc | 50.383ab |

| 3 | Marye | 62.33abc | 20.72defgh | 24.07ef | 31.46cdef | 40.72c |

| 4 | Worku | 27def | 17.03gh | 23.33ef | 29.62def | 39.62c |

| 5 | Akaki | 27.33def | 17.79gh | 24.83ef | 27.4ef | 37.37c |

| 6 | Kutaye | 30.67de | 18.52fgh | 24.47ef | 27.03ef | 35.91c |

| 7 | Fetenech | 22.67ef | 16.7h | 25.6def | 25.55f | 35.91c |

| 8 | Natoli | 56.33bc | 22.95bcdefg | 27.39def | 32.95cdef | 43.32abc |

| 9 | Minjar | 58bc | 22.96bcdefg | 28.49cdef | 30.36def | 39.61c |

| 10 | Dimtu | 55.33c | 26.3bcd | 32.56bcd | 34.81bcde | 42.96abc |

| 11 | Adet local | 34.67d | 22.2cdefgh | 30.37bcdef | 32.23cdef | 39.98c |

| Mean | 46.73 | 21.38 | 27.5 | 31.5 | 40.9 | |

| 1 | DZ-10-4 | 25def | 17.41gh | 24.13ef | 28.51ef | 37.72c |

| 2 | Shasho | 25.33def | 17.04gh | 22.95f | 30.72def | 40.72c |

| 3 | Areti | 59bc | 34.04a | 40.36a | 44.05a | 50.36ab |

| 4 | Habru | 68ab | 27.027bc | 30.73bcde | 41.47ab | 50.73a |

| 5 | Ejeri | 24def | 20efgh | 27.03def | 30.01def | 40.38c |

| 6 | Tji | 55.67c | 24.42bcdef | 29.61bcdef | 36.65abcd | 44.77abc |

| 7 | Yelbe | 58.67bc | 24.81bcde | 27.01def | 32.2cdef | 40.73c |

| 8 | Acose Dube | 67abc | 28.53ab | 36.27ab | 41.48ab | 51.49a |

| 9 | DEHERA | 18f | 18.51fgh | 27.73cdef | 33.69bcde | 41.43bc |

| 10 | HORA | 24.67def | 18.87efgh | 23.32ef | 32.21cdef | 41.10c |

| Mean | 42.5 | 23.1 | 28.9 | 35.1 | 43.9 | |

| LSD | 4.4.69 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 9.1 | |

| CV | 15.9 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 14.8 | 13.0 | |

Table 2: Mean value of incidence and severity on Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties on field experiment.

From 10 Kabuli type of chickpea varieties screened against Fusarium wilt, the highest percentage of incidence (68%) was recorded from the variety Habru and the lowest incidence (18%) was from the variety Dehera. Varieties like: Acos-dube, Areti, Yelbe and Tji were highly susceptible while Shasho, D-Z-10-4, Hora and Ejeri were moderately resistant. The only resistant variety from Kabuli chickpea variety is Dehera. Demisew [41] reported that new varieties have good genetic potential for disease resistance than old varieties. Thaware et al. [42] screened 50 chickpea varieties against Fusarium wilt and found that all the chickpea varities exhibited different reactions against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Ciceri.

Severity of Fusarium wilt

The result revealed there was highly significant difference at (p<0.01) for each consecutive week. From Desi type varieties, the highest disease severity (28.87%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest severity (16.7%) was recorded on the variety Fetenech in first week. In the second week, the highest severity (35.18%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest severity (23.33%) was recorded from the variety Worku. In the third week, the highest severity (38.51%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the least low (25.55%) was recorded from the variety Fetenech. In the fourth week, the highest severity (50.38%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest severity (35.91%) from Fetenech. The percentage of disease severity was increased with time.

From Kabuli chickpea varieties, the highest percentage of severity (34.04%) was recorded from the variety Areti and the lowest percentage of incidence (17.04%) from the variety Shasho in first week. The overall mean of percentage of severity in Kabuli chickpea varieties for four consecutive weeks were 23.06%, 28.9%, 35.09% and 43.95%. Percentage of severity increased with time similar to Desi chickpea varieties. The result of this study is in line with the findings of Maitlo et al., [23] who reported that the degree of disease severity of Fusarium wilt of chickpea increases from seedling to flowering stage and the highest severity was recorded at podding stage.

Influence of inoculum concentrations on disease incidence

In screen house, experiment three levels of the pathogen concentrations were artificially inoculated on the varieties Dube, Yelbe, Marye and Dimtu. From 5 ml level of inoculum concentration, the highest percentage of incidence (50%) was recorded from the variety Dube followed by Dimtu, (40%), while the lowest incidence (33.33%) was recorded from the variety Marye. From 10 ml, level of inoculum concentration of the pathogen, the highest percentage of incidence (60%) was recorded from the variety Dube, and the lowest (36.67%) was recorded from the variety Marye. From 15 ml level of inoculum concentration, the highest percentage of incidence (73.33%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest (50%) was from the variety Marye.

On all level of inoculum concentrations, the highest percentage of incidence was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest was recorded from Marye. The overall means of percentage of incidence on 5 ml, 10 ml and 15 ml was 39.9%, 45.8% and 59.16% (Table 3). This indicates that the aggressiveness of the pathogen increases with the level of inoculum concentration. Maitlo et al. [23] who conclude that the mortality of chickpea was positively correlated with the densities of inoculum concentration of Fusarium wilt.

| No. | Chick pea variety |

Incidence (%) at different level of concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 ml | 10 ml | 15 ml | ||

| 1 | Dube | 50.0 | 60.0 | 73.3 |

| 2 | Yelbe | 36.7 | 43.3 | 53.3 |

| 3 | Marye | 33.3 | 36.7 | 50.0 |

| 4 | Dimtu | 40.0 | 43.3 | 60.0 |

| 5 | Areti (control) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 39.9 | 45.8 | 59.2 | |

| LSD (5%) | 13.3 | 14.1 | 10.0 | |

| CV (%) | 22.8 | 21.1 | 12.2 | |

CV=Coefficient of Variance, LSD=Least Significant Difference

Table 3: Mean value of different level of inoculum concentration of the pathogen on incidence of Fusarium wilt in screen house experiment.

Influence inoculum concentration on disease severity

The result reveals that there was significant difference among the varieties and-inoculum concentration levels of the pathogen. There was no severity observed from the controlled variety (Areti). The highest percentage of severity was recorded in the third week from 15 ml inoculum concentration in all chickpea varieties except the controlled variety.

At the first week, from 5 ml level of inoculum concentration, the highest percentage of severity (37.8%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest (34.1%) was recorded from the remaining varieties. Similarly, from 10 ml inoculum concentration, the highest severity (48.2%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest 45.9% was recorded from Marye and Dimtu. In addition, from 15 ml concentration level, the highest severity (66.7%) was recorded from the variety Dimtu and the lowest (64.6%) was from Marye (Table 4).

| No | Chickpea varieties | Severity (%) at different levels of inoculum concentration | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st week | 2nd week | 3rd week | ||||||||

| 5 ml | 10 ml | 15 ml | 5 ml | 10 ml | 15 ml | 5 ml | 10 ml | 15 ml | ||

| 1 | Dube | 37.8 | 48.2 | 65.9 | 40.7 | 51.8 | 70.4 | 45.2 | 56.3 | 74.8 |

| 2 | Yelbie | 34.1 | 45.9 | 64.5 | 38.5 | 50.4 | 68.1 | 42.2 | 53.3 | 74.1 |

| 3 | Marye | 34.1 | 46.7 | 65.2 | 38.5 | 51.1 | 69.6 | 41.5 | 54.1 | 71.1 |

| 4 | Dimtu | 34.1 | 45.9 | 66.7 | 38.5 | 49.6 | 70.3 | 42.2 | 54.1 | 74.1 |

| 5 | Areti (control) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 35.0 | 46.7 | 65.6 | 39.1 | 50.7 | 69.6 | 42.8 | 54.4 | 73.5 | |

| LSD (5%) | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 10.7 | |

| CV (%) | 3.7 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.0 | |

LSD=Least Significant Difference, CV=Coefficient of Variance

Table 4: Mean value of severity of Fusarium wilt at different level of inoculum concentration.

At the second week from 5 ml inoculum concentration, the highest severity (40.7%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the lowest severity (38.5%) was recorded from Yelbe, Marye and Dimtu. Similarly, from 10 ml inoculum concentration, the highest severity (51.8%) was recorded from the variety Dube while the least 49.63% was recorded from the variety Dimtu. From 15 ml inoculum concentration, the highest severity (70.4%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the least 69.6% was recorded from the variety Yelbe (Table 4).

At the third week at 5 ml inoculum concentration, the highest severity (45.2%) was recorded from the variety Dube whereas the lowest 41.5% was recorded from the variety Marye. Similarly, from 10 ml of inoculum concentration, the highest severity (56.3%) was recorded from the variety Dube and the least 53.3% was recorded from the variety Yelbe. From 15 ml inoculum concentration, the highest severity (74.8%) while the least 71.1% was recorded from the varieties Yelbe and Dimtu (Table 4). The result indicated that the aggressiveness of the pathogen increases with inoculum concentration and time and in line with the findings of Maitlo et al. [23] who conclude that the mortality of chickpea was positively correlated with the densities of inoculum concentration of Fusarium wilt.

Conclusion

Evaluation of genetic variation in chickpea varieties is essential for effective selection in genetic improvement for disease resistance, agronomic and yield traits. The present study was done at field and screen house in west Gojam zone to identify the best resistant Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties against Fusarium wilt of chickpea. The field experiment was done using 11 Desi type and 10 Kabuli type chickpea varieties and the screen house experiment was done by artificial inoculation of three levels of the inoculum concentrations of Fusarium pathogen. Based on the results of experiment the following conclusions are made: There were no highly resistant varieties among Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties against Fusarium wilt of chickpea on field experiment. Among the screened 11 Desi type chickpea varieties three varieties were moderately resistant, two varieties were susceptible and six varieties were highly susceptible.

Among the screened Kabuli type chickpea varieties, one variety was resistant, four varieties were moderately resistant and five varieties were highly susceptible. Severity was increased with time on both field and screen house experiment. In screen house experiment, the highest disease incidence and severity were observed on 15 ml inoculum concentration of Fusarium wilt. The aggressiveness of the pathogen on both type chickpea varieties was increased with inoculum concentration and time.

Recommendation

Depending on the result of the experiment, the following recommendations are listed for future consideration. Chickpea breeders should develop highly resistant of both chickpea varieties against Fusarium wilt of chickpea. Further research should be conducted on the management of Fusarium wilt of chickpea using agronomic practices like seed rate, inter and intra row spacing, sowing date, sowing method and soil type. The field experiment should be repeated including the new developed Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties at different location to get the reliable result since the current experiment was done only in one location for a single season.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Debre-Zeit Agricultural Research Center, pulses improvement program, for providing experimental Desi and Kabuli chickpea varieties; Adet agricultural research center for providing research field for field experiment and laboratory equipments for screen house experiment; Debre Berhan University for providing financial support. The authors also thank Mr. Esmelalem Mihretu for his technical support and relevant advice in the laboratory experiment.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest and the research was conducted by keeping the ethics of scientific research methods and approaches.

REFERENCES

- Diapari M, Sindhu A, Bett K, Deokari A, Warkentin DT, et al. (2014) Genetic diversity and association mapping of iron and zinc concentration in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L). Genom 57: 459-468.

- http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home

- Gaur MP, Aravind KJ, Rajeev KV (2012) Impact of genomic technologies on chickpea breeding strategies. Agron 2: 200-203.

- Asrat Z (2017) Significance and management of chick pea wilt/root rot and future prospects in Ethiopia. A review. Int J Life Sci 5: 117-126.

- Agarwal G, Jhanwar S, Priya P, Singh VK, Saxena MS, et al. (2012) Comparative analysis of kabuli chickpea transcriptome with desi and wild chickpea provides a rich resource for development of functional markers. PLoS ONE 7: 52443.

- Shiferaw B, Jones R, Silim S, Teklewold H, Gwata E (2007) Analysis of production costs, market opportunities and competitiveness of Desi and Kabuli Chickpeas in Ethiopia. IPMS Working Paper 3. ILRI, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia p: 48.

- Castro P, Rubio J, Millán T, Gil J, Cobos MJ (2012) Fusarium wilt in chickpea: General aspect and molecular breeding. In Fusarium: Epidemiology, Environmental Sources and Prevention; Rios, T.F., Ortega, E.R., Eds. Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA pp: 101-122.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency) (2016) Agricultural sample survey report on area and production of crops private peasant holdings. Meher Season pp: 2-4.

- Menale K, Bekele S, Solomon A, Tsedeke A, Geoffrey M, et al. (2009) Current situation and future outlooks of the Chickpea Sub-sector in Ethiopia. ICRISAT, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Tebkew D, Chris O (2016) Current status of wilt/root rots diseases in major chickpea growing areas of Ethiopia. Arch Phytopatholo Plant Prot 49: 222-238.

- Bekele S, Jones R, Silim S, Tekelewold H, Gwata E (2007) Analysis of production costs, market opportunities and competitiveness of desi and kabuli chickpea in Ethiopia Chand H, Khirbat SK (eds.) chickpea wilt and its management. A Rev Agricul Revolut 30: 1-12.

- Millan T, Clarke H, Siddique K, Buhariwalla H, Gaur P, et al. (2006) Chickpea molecular breeding: New tools and concepts. Euphytica 147: 81-103.

- MoARD (2008) Ministry of agriculture and rural development crop variety development. Depart Crop Varie Reg p: 11.

- EEPA (Ethiopian Export Promotion Agency) (2004) Ethiopian pulses profile. Product Development and Market Research Directorate, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Pande S, Sharma M, Guar PM, Tripathi S, Kaur L, et al. (2011) Development of screening techniques and identification of new sources of resistance to Ascochyta blight disease of chickpea. Aust J Plant Pathol 40: 149-156.

- Chaudhry MA, Ilyas MB, Muhammad F, Ghazanfar MU (2007) Sources of resistance in chickpea germplasm against fusarium wilt. Mycopatho 5: 17-21.

- Malik SR, Shabbir G, Zubur M, Iqball SM, Ali A (2014) Genetic diversity analysis of morpho-genetic traits in Desi Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Inter J Agri Bio 16: 956-960.

- Merkuz A, Getachew A (2012) Influence of chickpea Fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceris) on Desi and Kabuli-type of chickpea in integrated disease management option at wilt sick plot in North Western Ethiopia. Inter J Curr Res 4: 046-052.

- Upadhyaya HD, Thudi M, Dronavalli N, Gujaria N, Singh S, et al. (2011) Genomic tools and germplasm diversity for chickpea improvement. Plant Gen Res Chara & Util 9: 45-58.

- Schneider K, Anderson L (2010) Yield gap and productivity potential in Ethiopian agriculture: staple grains and pulses. Evans School Policy Analysis and Research (EPAR) of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Evans Schools of Public Affairs, University of Washington p: 98.

- Jiménez-díaz RM, Jiménez-gasco MM (2011) Integrated management of Fusarium Wilt diseases. pp: 177-215.

- Warda J, Mariem B, Amal B, Mohamed B, Mohamed K (2017) A review on Fusarium Wilt affecting chickpea crop, Field Crops Laboratory, University of Carthage, INRAT.

- Agrios GN (2005) Plant pathology 6th Edition. San Diego, C. A. Elsevier Academic Press p: 948.

- Iqbal SM, Haq IU, Bukhari A, Ghafoor A, Haqqani AM (2005) Screening of chickpea genotypes for resistance against Fusarium wilt. Mycopatho 3: 1-5.

- Ahmad Z, Mumtaz AS, Nisar M, Khan N (2012) Diversity analysis of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) germplasm and its implications for conservation and crop breeding. Agri Scien 3: 723-731

- Landa BB, Navas-Cortés, JA Jiménez-Díaz, RM (2004) Integrated management of fusarium wilt of chickpea with sowing date, host resistance, and biological control. Phytopathl 94: 946-960.

- Asnakech T (2014) Genetic analysis and characterization of faba bean (Vicia faba) for resistance to chocolate spot (Botrytis fabae) disease and yield in the Ethiopian highlands. PhD dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. Rep South Africa p: 266.

- Bakhsh A, Iqbal SM, Haq IK (2007) Evolution of chickpea germplasm for wilt resistance. Pak J Biot 39: 583-593.

- Karimi K, Amini J, Harighi B, Bahramnejad B (2012) Evaluation of biocontrol potential of Pseudomonas and Bacillus spp. against Fusarium wilt of chickpea. Australian J Crop Scie 6: 695-703.

- Nazir MA, Khan MA, Ali S (2012) Evaluation of national and international chickpea germplasm for resistance against Fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris) in Pakistan. Paki J Phytopathl 24: 149-151.

- Seid A, Melkamu A (2006) Chickpea, lentil, grasspea, fenugreek and lupine disease research in Ethiopia. In: Ali, K et al. eds.). Food and forage legumes of Ethiopia: progress and prospects. Proceedings of the Workshop on Food and Forage Legume, 2003 Sept 22-26, Addis Ababa: Int Center Agricultu Res Dry Areas (ICARDA) pp: 215-220.

- Ekhlass HM, Nayla E, Haroun MA, Elsiddig A (2016) Control of chickpea wilt caused by fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris with botanical extracts and fungicides. Int J Curr Micro & Appl Scien 5: 360-370.

- Van-der M (1987) Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), Origin, history and taxonomy of chickpea. P.11-34. In: M.C. Saxena and K.B. Singh (ed.), The Chickpea. CABI, Cambrian News Ltd, Aberystwyth, UK.

- Maitlo SA, Syed RN, Rustamani MA, Khuhro RD, Lodhi AM (2016) Influence of inoculation methods and inoculum levels on the aggressiveness of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceris on chickpea and plant growth. Inte J Agri Bio 18: 31-36.

- Yang X, Chen L, Yong X, Shen Q (2011) Formulations can affect rhizosphere colonization and biocontrol efficiency of Trichoderma harzianum SQR-T037 against Fusarium wilt of cucumbers. Biol Fert f Soil 47: 239-248.

- Chen W, Muehlbauer FJ (2003) An improved technique for virulence assay of Ascochyta rabiei on chickpea. Int Chickpe Pigeonp Newslett 10: 31-33.

- Megersa T, Losenge T, Chris OO (2017) Survey of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L) Ascochyta blight (Ascochyta rabiei Pass.) disease status in production regions of Ethiopia. Plantea 5: 23-30.

- Mujeebur RK, Shahana MK, Fayaz AM (2004) Biological control of Fusarium wilt of chickpea through seed treatment with the commercial formulation of Trichoderma harzianum and/or Pseudomonas fluorescens. Phytopatholog Medite 43: 20-25.

- Sharma KD, Chen W, Muehlbauer FJ (2005) Genetics of chickpea resistance to five races of Fusarium wilt and a concise set of race differentials for F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris. Plant Dis 89: 385-390.

- Gomez KA, Gomez AA (1984) Statistical procedures for agricultural research. 2nd edition, A Wiley Interscience Publications, New York p: 680.

- Demissew T (2010) Genetic gain in grain yield and associated traits of early and medium maturing varieties of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill]. An M. Sc. Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies of Haramaya University.

- Thaware DS, Gholve VM, Ghante PH (2017) Screening of chickpea varieties, cultivars and genotypes agains Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri. Int J Micro Appli Scien 6: 896-904.

Citation: Ayana A, Hailu N, Taye W (2019) Screening Desi and Kabuli Chick Pea Varieties against Fusarium Wilt Resistance in West Gojam, Northwestern Ethiopia. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 10: 474.

Copyright: © 2019 Ayana A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.