Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- CiteFactor

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture (AGORA)

- Electronic Journals Library

- Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI)

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Scholarsteer

- SWB online catalog

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2020) Volume 11, Issue 11

Quantifying the Estimation and Abundance of Plant Diversity of Shigar Valley, Gilgit -Baltistan, Pakistan

Saif Ullah1, Muhammad Zaman2, Liu Jiaqi1, Yaseen Khan3, Shakir Ullah4 and Tian Gang1*2College of Wildlife Resource, Northeast Forestry University, China

3Key Laboratory of Plant Nutrition and Agri-environment in Northwest China, Ministry of Agriculture, College of Natural Resources and Environment, Northwest A&F University, China

4Key Laboratory of Plant Ecology, Northeast Forestry University, P.R. China

Received: 05-Oct-2020 Published: 13-Nov-2020, DOI: 10.35248/2157-7471.20.11.522

Abstract

The studies were carried out from July 2017 to March 2018 in Shigar valley different Union Councils. The area lies between 7444 feet to 11694 feet from Above sea level in the Alpine zone including, Niali Nallah, Laxar Nallah, Nallah, Markuja union, Marapi union, Chorkah union, Gulapur. The study sites were randomly selected based on (1) herbs or shrubs land on the field periphery, (2) open grassland and arable land associated with sparse vegetation on rocks, stones, (3) forest land and open lands associated with sparse tree vegetation catchment of river and (4) forest land and arable land associated with dunes and rocky terrain. The quadrate method was used to record of vegetation from the selected study sites. A total of 59 plants species both medicinally and economically important were recorded at four study sites of CKNP and revealed that 30 herbs followed by 14 trees, 11 kinds of grass, and 4 shrubs respectively the dominant tree species recorded from all habitat types were Juniper sexcelsa, Elaeagnus ambulate, Morus alba, Salix Wilhelmina and Populus nigra. The most common herbs recorded were Artimisa brevifolia, Tanacetum, Echinops echinatus, Capparis sponsia, Ephedra intermedia, Peganum harmala, Daucus carota, Medicago sativa, Typha lotifuliya and Astragalus rhizanthus. The dominant shrubs were Rosa webbina, Hippophae rhamnoides, Sophora Molis and Myricaria germanica. The grasses recorded in the study area were Poa Alpina, Setaria Viridis, Hetropogon contortus, Cynodon dactylon, Taraxacum oritinlis, Trifolium repens and Cascuta reflexa. These plants are also used by local communities for fuelwood and timber. This study will be beneficial for locals and governments for the protection and conservation of this indigenous flora as well as fauna in the future.

Keywords

Gilgit Baltistan; Shigar Valley; Ethnobotanical study; Floristic Diversity

Introduction

Mountain landforms shield about one-quarter of the land surface and host 12% world’s population [1]. These landforms have excessive influence on the climatic, biological, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of any region. In Pakistan, a substantial rural population is existing in the mountain ranges of the Karakorum, Himalaya, and Hindu Kush. The Karakorum ranges frame profound incised valleys in the extreme north of Pakistan, and afford several services to dwellers such as timber, fuel wood, fodder, herbal medicines, etc. Because, harsh climate, remoteness, and challenging access hamper progress in elementary services chiefly, education and health [2].

Therefore, mountain people are measured as the poorest and deprived population. Additionally, the residents of high mountain areas are more susceptible to several diseases owing to the unsympathetic mountains’ environment with unpredicted variations in seasonal temperature, light intensity, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and poor domestic hygiene [3]. The health services delivered by government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are next to nothing for the residents living in these distant areas. Accordingly, in such environments plant founded old-fashioned therapies are the primary health care cause to diminish numerous health syndromes. Baltistan is a conventional mountainous region of Northern Pakistan with an average altitude of 3555 m above sea level. Traditionally, it has often been mentioned as “Western Tibet” or “Little Tibet” [4,5].

The regions of the Baltistan region lie sporadically at acclivities and in the unfathomable mountains of Karakorum and Himalaya with the distinctive landscape, climate, flora, and fauna. However, remoteness, difficult access, and insufficient funding may be the major handicaps to conduct field surveys in these areas. Only limited Researchers [6,7]. have conducted an ethnobotanical survey in some parts of Northern Pakistan. Therefore, precise inadequate ethnobotanical literature is presented in the region [8].

Human beings have been consuming plants since the earliest times for various determinations and early on they particularly developed numerous traditions of consuming plant resources to stabilize diseases [9,10]. Many field studies in the last periods have shown that traditional peoples, local communities, and indigenous societies around the world retain an incredible resident plant information, curiously fixed into daily practices and generally orally transmitted [11,12]. Natural resources and linked biotic diversity provide the source of livelihood for human populations. Subsequently, humans have an excessive influence on local flora and vice versa [13].

Although several former ethnobotanical surveys have been piloted in surrounding areas [14-16], many of these studies did not use quantitative methods [17]. These floras and orchard trees have therapeutic value; also fascinate tourists in the valleys, and pasture land offers forage for indigenous livestock, thus subsidizing to the local economy. The major plant species are Rosa webbiana, Hippophae rhomboids, and Berbers Lyceum. There are almost forty-seven families of traditional medicinal and twenty-two families of indigenous plants found in CKNP [6]. The vegetation characterized in CKNP was dominantly alpine pastures, meadows, and unfrosted grassland with shrubs land communities. The study sites were categorized as forest lands, grasslands, shrubs lands, and open lands depending upon specific topography. A large proportion of the valley population is very poor and depends upon agriculture, livestock rearing, and the production of fuelwood, wool blankets (Qaar) [3].

Shigar valley is situated in the Karakorum Ranges and is the home of several peaks (including K2), glaciers, and hot springs, which have always been the most favoured tracking places for visitors across the country and abroad. Ethnobotany is a recently familiarized and quickly flourishing field in this region and is gaining satisfactory consideration by researchers. While numerous ethnobotanical surveys have been conducted in different parts of Pakistan. However, the Northern parts of the country are still unwell discovered. Hence, the present survey is designed to provide, baseline data for estimation and abundance of plant diversity in the study area and sharing species in different habitat types for conservation and management purposes.

Materials and Methods

Study area

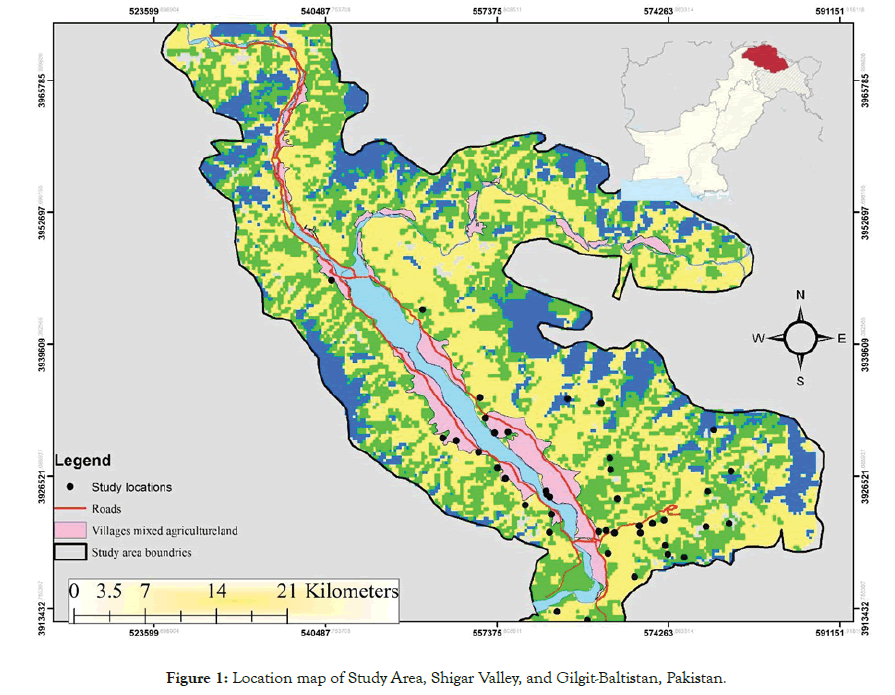

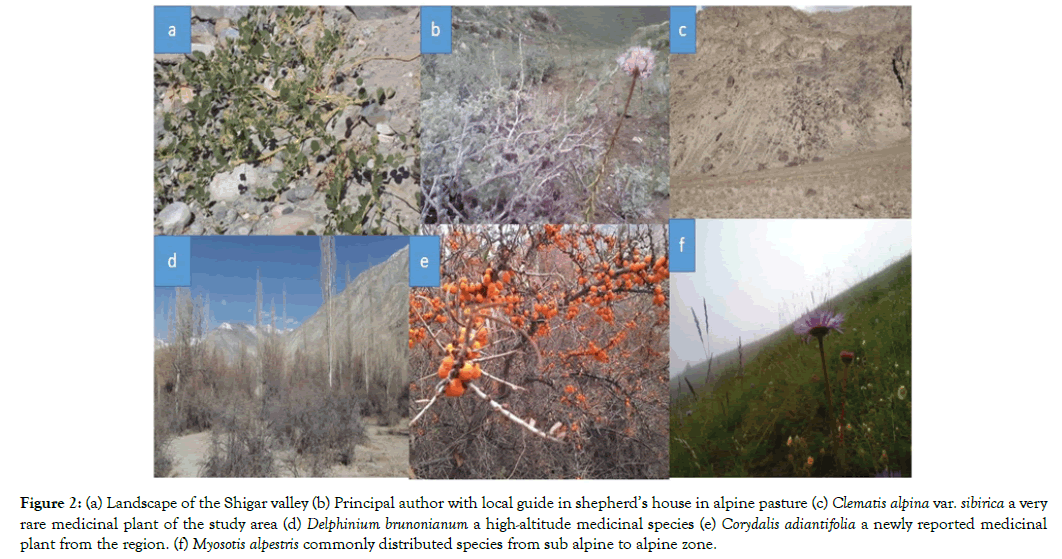

Shigar Valley is a portion of the central Karakorum ranges located in the north of Skardu town at the right bank of the river Indus (Figure 1). It lies at 25° 25"32"N latitude and 75°42"59"E longitude and covers an area of 4373 sq. km with altitudinal amplitudes of 2, 260 to 8611 m above sea level [18]. Central Karakoram National Park lies in a dry temperate ecological zone. Its climate varies due to the impact of higher mountains and rain shadows and even varies between lowlands and valleys. The valleys are dry with the annual precipitation around (200 mm) with a maximum of almost (600 mm) at elevations of (13,000 m) [19]. In the Winter Season temperature falls below –25°C while in summer it is very pleasant and ranges from 20-35°C [20]. Various investigators have studied the flora from different locations of Northern areas of Pakistan [21] (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Location map of Study Area, Shigar Valley, and Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan.

Figure 2: (a) Landscape of the Shigar valley (b) Principal author with local guide in shepherd’s house in alpine pasture (c) Clematis alpina var. sibirica a very rare medicinal plant of the study area (d) Delphinium brunonianum a high-altitude medicinal species (e) Corydalis adiantifolia a newly reported medicinal plant from the region. (f) Myosotis alpestris commonly distributed species from sub alpine to alpine zone.

Data collection

This study was conducted in August 2017 to July 2018 in Shigar Valley Central Karakoram National Park (CKNP), Pakistan. During field trips, male experts, shepherds, herder, hunters, and women housewife’s expert in kitchen gardening were interviewed personally regarding the uses of important plants. A line transects sampling method used for collected plants spatial distribution, in total 38 transects were designed and each transect were 4 km apart from each other to avoid multiple counts. All study sites were randomly selected based on (1) herbs or shrubs land on the field periphery, (2) open grassland and arable land associated with sparse vegetation on rocks, stones, (3) forest land and open lands associated with sparse tree vegetation catchment of the river, (4) Forest land and arable land associated with dunes and rocky terrain. The quadrate method was used to record potential vegetation analysis from the selected study sites as described by Schemnitz [22]. The total area of the Shigar valley is 8500 km2. The total area covered in this study was 48000 m2. The stratified sample size was (600 m × 200 m) for one site. A stratified sample size was carried out by (10 m × 10m) for (all vegetation types) taken randomly. The original sample size was 12000 m2 for one site; twelve plots of 100 m2 were covering 10 percent of the total area (1200 meter). The quadrate size was used for trees (10 m × 10 m), shrubs (4 m × 4 m), and herbs/grasses (1 m × 1 m).

Data analysis

Frequency and the cover of plant species falling inside the quadrates were recorded and samples of unidentified plants were collected with specific tagged with the name and identified from Karakorum International University, Gilgit, and some specimens of plants were identified from the Department of Botany, PMAS-Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi [3]. The density, relative density, frequency, relative frequency, cover, relative covers, and importance value index (IVI) of recorded plant species in the study area of selected habitats types were calculated by using the following formulae. All the analyses were carried out in the micro excel software version 2013.

Density (D)=Total number of species recorded in all quadrates/ Total area sampled

Relative Density (RD) = (Total numbers of individuals of a species/ Total no of individuals of all species)×100

Frequency (F)=Number of quadrats in which species occurs/Total number of quadrates

Relative Frequency (RF)=(Frequency value of species/ Sum frequency value of all species)×100

Cover (C)=Cover of individuals of a species/Total cover of all species

Relative Cover (RD)=(Cover of individuals of a species/Total cover of all individuals of all species)×100

Importance Value Index (IVI) = Relative density (RD) + Relative frequency (RF) + Relative cover (RCo) Plant communities were calculated based on dominant species having a larger importance value in the given ecological community [22].

Results

The study sites UC Marapi extends from the gateway of Kothangpian (35°21'47.81"N, 75°44'24.82"E) to Ghazapa (35°25'5.05"N, 75°45'11.65"E). Two sampling areas were selected from the study site UC Markunja; upper site of Chipping near historical Shigar fort (35°25'27.43"N, 75°44'34.83"E) to Taherping (35°26'17.90"N, 75°44'8.84"E). The second study site UC Markuja extends from Bounpi ranga (35°26'3.02"N, 75°43'15.27"E) to Chorkah ranga (35°27'49.17"N, 75°41'15.65"E). The study site UC iGuipure include Quqla (35°22'56.84"N, 75°42'11.43"E) human-made forest to the second gateway of Shigar valley to Bonpa Gulapur (35°27'55.75"N, 35°27'55.75"N) near the catchment of the river.

Study of habitat

Habitat types; 1; Herbs land/shrubs with natural vegetation, 2; Open grassland and arable land having sparse vegetation, 3; Forest and open land with agricultural land boundaries and sparse tree vegetation on river catchment, and 4; Forest and arable land with dunes and rocky terrain. A total of 59 plant species both medicinally and economically important were recorded at four study sites of CKNP including 30 herbs followed by 14 trees, 11 kinds of grass, and 4 shrubs.

Herbs land/shrubs with natural vegetation

The results of plant species found in habitat-1 are presented in Table 1. Dominant grasses recorded in the habitat one was Poa Alpina (IVI=420.41), followed by Setaria viridis (IVI=51.30), Hetropogon contortus (IVI=40.27), and Poa bulbus (IVI=16.00) respectively. Dominant herbaceous plants species were Sophora mollis (IVI=131.39) followed by Artimisa brevifolia (IVI=107.64), Plantago major (IVI=56.50), Tanacetum senecionis (IVI=41.52), Polygonum hydropiper (IVI=41.48), Thymus serpyllum (IVI=41.10), Saccharum bengalense (IVI=41.10), Capparis sponsia (IVI=33.18), Ephedra garardina (IVI=17.67), Carum bulbocastanum Koch (IVI=7.70), Delphinium brunonianum Royle (IVI=7.61) Chenopodium faliosum (IVI=6.09) and Ephedra intermedia (IVI=6.74) respectively. Dominant shrub species was Rosa webbina (IVI=38.73) and tree species was Juniperus excelsa (IVI=12.57).

| Plant species | R.D | R.F | R.C | IVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artimisa brevifolia | H | 14.39 | 18.91 | 74.32 | 107.64 |

| Tanacetum senecionis | H | 36.58 | 2.7 | 2.23 | 41.52 |

| Ephedra gardina | H | 8.96 | 2.7 | 6 | 17.67 |

| Plantago major | H | 52.26 | 2.7 | 1.53 | 56.5 |

| Deliphinumbrunonianum | H | 3.73 | 2.7 | 1.17 | 7.61 |

| Polygonum hydropiper | H | 35.84 | 2.7 | 2.94 | 41.48 |

| Thymus serphyllus | H | 33.1 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 41.1 |

| Carum bulbocastnum | H | 3.23 | 2.7 | 1.76 | 7.7 |

| Hydrpogon contortus | G | 33.1 | 5.4 | 1.76 | 40.27 |

| Saccharum bengalense | H | 33.1 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 41.1 |

| Sataria viridis | G | 47.53 | 2.7 | 1.06 | 51.3 |

| Poa alpine | G | 379.81 | 16.21 | 24.38 | 420.41 |

| Poa bulbus | G | 10.95 | 2.7 | 2.35 | 16 |

| Chenopodium foliosum | H | 1.74 | 2.7 | 1.64 | 6.09 |

| Sphora mollis | S | 122.45 | 5.4 | 3.53 | 131.39 |

| Rosa webbina | S | 11.2 | 13.51 | 14.01 | 38.73 |

| Junipersexsula | T | 3.98 | 2.7 | 5.88 | 12.57 |

| Ephedra regelione | H | 0.74 | 5.4 | 0.58 | 6.74 |

| Capparis sponsia | H | 17.42 | 8.1 | 7.65 | 33.18 |

Table 1: Plant species recorded from herbs land/shrubs with natural vegetation in CKNP.

Open grassland and arable land having sparse vegetation

The results of plant species found in habitat-2 are given in Table 2. Dominant grasses recorded in the habitat were Cynodon dactylon (IVI=48.10) and Pancicum species (IVI=31.41). The most densely distributed herbs species were Eschinops echinatus (IVI=159.16) followed by Artimisa Brevilolia ( IVI=131.36), Artimisa rutifolia (IVI=42.06), Peganum harmala (IVI=26.09), Capparis sponsia (IVI=20.61), Ephedra garardina (IVI=11.31), Mentha logifoliya(IVI=6.23), Ephedra intermedia (IVI=5.96), Cousinia thomsonii (IVI=4.78), Rheum spiciforme Royle (IVI=4.55), Nepeta Floccosa (IVI=4.31), Chenopodium album (IVI=3.89) and Circium falconori (IVI=3.31) respectively. The dominant tree species recorded in the area were Elaeagus ambulate (IVI=14.86) followed by Platanus orientalis (IVI=10.88) and Robina pesudoacacia (IVI=7.35) respectively.

| Plant species | R.D | R.F | R.C | IVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Â Artimisa brevilolia | H H | 71.25 | 17.64 | 42.46 | 131.36 |

| Artimisa rutifolia | H | 15.21 | 5.88 | 20.96 | 42.06 |

| Capparis sponsia | H | 2.24 | 14.7 | 3.66 | 20.61 |

| Ephedra garadina | H | 1.76 | 5.88 | 3.66 | 11.31 |

| Ephedra intermidia | H | 0.4 | 2.94 | 2.62 | 5.96 |

| Echinops echinatus | H | 75.1 | 29.41 | 54.65 | 159.16 |

| Panicium species | G | 12.89 | 8.82 | 9.69 | 31.41 |

| Mentha logifoliya | H | 2.64 | 2.94 | 0.65 | 6.23 |

| Robina pseudoacacia | T | 0.16 | 5.88 | 1.31 | 7.35 |

| Elaeagus ambulate | T | 1.12 | 5.88 | 7.86 | 14.86 |

| Cynodon dactylon | G | 32.98 | 8.82 | 6.29 | 48.1 |

| Circiumfalconori | H | 0.24 | 2.94 | 0.13 | 3.31 |

| Nepeta faloccosa | H | 0.72 | 2.94 | 0.65 | 4.31 |

| Cousinia thomsonii | H | 0.4 | 2.94 | 1.44 | 4.78 |

| Trifoliu pretense | H | 0.24 | 2.94 | 1.17 | 4.36 |

| Rheum spiciforme | H | 0.96 | 2.94 | 0.65 | 4.55 |

| Platanus orientalis | T | 0.08 | 2.94 | 7.86 | 10.88 |

| Chenopodium album | H | 0.56 | 2.94 | 0.39 | 3.89 |

| Peganun harmala | H | 6.72 | 11.76 | 7.6 | 26.09 |

Table 2: Plant species recorded from open grassland and arable land having sparse vegetation in CKNP.

Forest and open land with agricultural land boundaries

The data on the important plant species present in the habitat-3 are presented in Table 3. The dominant grasses recorded in the area were Taraxacum oritinlis (IVI=38.71) and Cynodon dactylon (IVI=37.76). The dominant herbs were Daucus carota (IVI=65.84) followed by Medicago sativa (IVI=54.01), Equesitum arvensis (IVI=12.84), and Circium falconeri (IVI=4.03) respectively. The shrubs species present in the area were Hippophaerhamnoides (IVI=115.12) followed by Sophora Mollis (IVI=18.80) and Arundo donex (IVI=11.78). Many tree species recorded in the area were economically important for wood and timber. These are Malus Pumila (IVI=128.34) followed by Morus Alba (IVI=27.17), Populus nigra (IVI=15.55), Populus ciliate (IVI=12.97), Salix wilhelmsiana (IVI=13.39), Elaeagus ambulate (IVI=11.20), Robina pseudoacacia (IVI=10.68) and Morus Rubra (IVI=6.10) respectively.

| Plant species | R.D | R.F | R.C | IVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippophae rhamnoides | S | 76.87 | 13.51 | 24.73 | 115.12 |

| Morus alba | T | 0.9 | 10.81 | 15.45 | 27.17 |

| Morus rubra | T | 0.75 | 2.7 | 2.65 | 6.1 |

| Salix wilhelmsiana | T | 1.8 | 5.4 | 6.18 | 13.39 |

| Eleagus ambulate | T | 5.85 | 2.7 | 2.65 | 11.2 |

| Populus cillate | T | 0.45 | 8.1 | 4.41 | 12.97 |

| Populus nigra | T | 5.85 | 8.1 | 1.59 | 15.55 |

| Robina pseudoacacia | T | 3.6 | 5.4 | 1.67 | 10.68 |

| Cynodon dactylon | G | 31.53 | 2.7 | 3.53 | 37.76 |

| Malus pumala | T | 123.87 | 2.7 | 1.76 | 128.34 |

| Sophora mollis | S | 0.15 | 5.4 | 13.25 | 18.8 |

| Pronus amaydalus | T | 62.16 | 5.4 | 0.88 | 68.45 |

| Taraxacumoritinlis | G | 29.27 | 8.1 | 1.32 | 38.71 |

| Medicago sativa | H | 49.54 | 2.7 | 1.76 | 54.01 |

| Arendo donex | S | 2.4 | 5.4 | 3.97 | 11.78 |

| Daucus carota | H | 59.6 | 2.7 | 3.53 | 65.84 |

| Equesitum arvensi | H | 6.6 | 2.7 | 3.53 | 12.84 |

| Circium falconeri | H | 0.45 | 2.7 | 0.88 | 4.03 |

Table 3: Plant species recorded from forest and open land with agricultural land boundaries in CKNP.

Forest and arable land with sand dunes and rocky terrain

The data on the plant species present in the habitat-4 are given in Table 4. The dominant grass species recorded in the area were Trifolium repens (IVI=68.27) and Cascuta reflexa (IVI=26.97). The herbs recorded in the study area were Artimisa rutifoliya (IVI=189.86), Eschinops echinatus (IVI=108.31), Typha lotifuliya (IVI=82.42), Astragalus rhizanthus (IVI=59.43), and Peganum harmala (IVI=19.90) respectively. The most common shrubs present in the area were Hippophae rhamoids (IVI=199.25), Myricaria germanica (IVI=85.60) and Barbaris lyceum (IVI=23.04). The tree species recorded in the area were Salix wilhelmsiana (IVI=29.83), Elaeagus ambulate (IVI=29.07), Fraxinus xanthoxyloides (IVI=18.79), Salix Tetrasperma (IVI=18.67), and Prunus armeniaca (IVI=6.68).

| Plant species | R.D | R.F | R.C | IVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippophae harmonides | S | 144.59 | 21.62 | 33.03 | 199.25 |

| Myricaria germanica | S | 42.94 | 13.51 | 29.15 | 85.6 |

| Babaris laycium | S | 3.45 | 8.1 | 11.48 | 23.04 |

| Salix wilehelmsiana | T | 4.05 | 8.1 | 17.66 | 29.83 |

| Eleagus ambulate | T | 2.4 | 13.51 | 13.16 | 29.07 |

| Salix tetrasperma | T | 1.5 | 10.81 | 6.36 | 18.67 |

| Astragalus rhizanthus | H | 42.49 | 8.1 | 8.83 | 59.43 |

| Ranunculus repens | H | 39.63 | 5.4 | 1.76 | 46.81 |

| Artimisa rutifoliya | H | 149.84 | 13.51 | 26.5 | 189.86 |

| Cascuta reflexa | G | 18.91 | 5.4 | 2.65 | 26.97 |

| Fraxinus xanthroxyloides | T | 1.8 | 10.81 | 6.18 | 18.79 |

| Ormalotheca norvegicum | H | 3.9 | 5.4 | 2.91 | 12.22 |

| Anthriscus sylvestris | G | 4.95 | 8.1 | 1.41 | 14.47 |

| Peganum harmala | H | 14.11 | 2.7 | 3.09 | 19.9 |

| Typha rotifoliya | H | 69.06 | 5.4 | 7.95 | 82.42 |

| Pronus armeniaca | T | 0.45 | 2.7 | 3.53 | 6.68 |

| Trifolium repens | G | 63.36 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 68.27 |

| Eschinops eschinatus | H | 84.23 | 16.21 | 7.86 | 108.31 |

Table 4: Plant species recorded from forest and arable land with sand dunes and rock terrain in CKNP.

The dominant trees species recorded from all habitat types were Juniperus excelsa, Elaeagus ambulate, Morus alba, Salix wilhelmsiana, and Populusnigra. The most common herbs recorded were Arimisa brevifolia, Tanacetum senecionis, Eschinops echinatus, Capparis sponsia, Ephedra intermedia, Peganum harmala, Daucus carota, Medicago sativa, Typha lotifuliyaand Astragalus rhizanthus. The dominant shrubs were Rosa webbina, Hippophae rhamnoide, Sophora Mollis, Myricaria germanicaand Barbaris lycium. The grasses recorded in the study area were Poa alpina, Sataria viridis, Hetropogon contortus, Cynodon dactylon, Taraxacum oritinlis, Trifoliumrepens and Cascuta reflexa.

In spite of the fact that these plant species were found in all habitat’s types in study area. But they have distinctive IVI value in each habitat; such as Juniperus excelsa has highest value in herbs/shrubs land. But Malus pumala has highest IVI value in the forest and open and Eleagus ambulate has the highest IVI value in the forest and arable land among all tree species in four selected habitats; open land, grassland, herbs land. Herbs species; Hippophae rhamnoideshas highest IVI value in the forest and arable land associated with dunes. But Rosa webbina has the highest IVI value in herbs/shrubs land among the all selected habitats in CKNP. Herbs plant Eschinop eschinatus has the highest IVI value in open grass and arable land rather than other habitat types and among the grasses, Poa Alpina has the highest IVI value in herbs/shrubs land. However, these plants are also used by local communities for fuelwood and timber.

Discussion

We found that plants species were spatially has distributed in the different selected sites, shrubs were more dominated plants in this regions as compared to others species The forest resources are unlawfully used for economic profits devoid of generous a single thought to the contrary future views of such activities and their influence on the flora of the region. Wilson [23] Stated that the worst thing that can happen during the 1980s that will take millions of years to correct the loss of genetic and species diversity by the damage of natural environments. Under present situations, it is estimated that about 50,000 higher plant species that is onefifth of the prevailing total in northern Pakistan. Two such studies suggest that Pakistan’s woody biomass is decreasing at a rate of 4-6% per year [24].

The relative valuation of present bids of medicinal plant species with described literature shown solid heterogeneity in folk uses. These conclusions exhibited that most of the species are limited in the mountains of the Karakorum, which have seldom been described before. In the regional disparity, our study showed substantial harmony with the work conducted by Hussain, et al. [25] in the central Karakorum Range [26] and to some amount with the ethnobotanical survey approved out in the Deosai plateau (Western Himalaya) Baltistan region [7,24]. While both studies were attentive on Balti communities, however, present assessment gives solid clues of the differences in ethnobotanical uses concerning topographical location and change in flora type [26,27].

The most common herbs recorded were Arimisa brevifolia, Tanacetum senecionis, Eschinops echinatus, Capparis sponsia, Ephedra intermedia, Peganum harmala, Daucus carota, Medicago sativa, Typha lotifuliya and Astragalus rhizanthus these herbs locally people used as a medicinal treatments and fodder. However [28] described Rosaceae as the most dominant family from different valleys of Himalaya and Karakorum ranges of mountains [8,28]. These results show the ample ethnic knowledge, different selection, and rich variety of medicinal flora of the region. Residents of the Shigar Valley use cultivated and wild plant species (73.80 and 22.19%, respectively) in traditional drug therapies, which is in contract with a former study conducted in Haramosh and Bugrote valleys, in Gilgit-Pakistan [29]. Except for Equisetum arvense and Ephedra gerardiana rest of the species were angiosperms. The prevailing trees species recorded from all habitat types were Juniperu sexcelsa, Elaeagus ambulate, Morus albam, Salix wilhelmsiana and Populusnigra. The most common herbs recorded were Arimisa brevifolia, Tanacetum senecionis, Eschinops echinatus, Capparis sponsia, Ephedra intermedia, Peganum harmala, Daucus carota, Medicago sativa, Typha lotifuliya, and Astragalus rhizanthus. Locally people used trees for fruits manufacture and timber, but these trees slowly declining above sea line due to fuel wood cutting. The climatic circumstances, wide-spreading and easy access may be the reasons behind prevailed herbaceous habit in the area [30].

Dominant grasses recorded in the habitat were Cynodon dactylon (IVI=48.10) and Pancicum species (IVI=31.41). The most thickly distributed herbs species were Eschinops echinatus (IVI=159.16) followed by Artimisa Brevilolia (IVI=131.36), Artimisa rutifolia (IVI=42.06), Peganum harmala (IVI=26.09), Capparis sponsia (IVI=20.61), Ephedra garardina (IVI=11.31), Mentha logifoliya (IVI=6.23), Ephedra intermedia (IVI=5.96), Cousinia thomsonii (IVI=4.78), Rheum spiciforme Royle (IVI=4.55), Nepeta Floccosa (IVI=4.31), Chenopodium album (IVI=3.89) and Circium falconori (IVI=3.31) respectively. Human beings have been consuming plants since ancient times for many dedications and early on they particularly developed numerous ways of using plant resources in order to counteract diseases [9,10]. Many field studies in the last decades have shown that traditional peoples, local communities, and indigenous societies around the world retain an incredible local plant familiarity, remarkably embedded into daily practices and mainly orally transmitted [11,12]. Natural resources and related biological diversity provide the source of livelihood for human populations. Subsequently, humans have an excessive influence on local vegetation and vice versa [13].

The present study demonstrated different medicinal flora in the territories of the Gilgit-Baltistan Mountains. The limited alliance of medicinal plants, mountain restricted distribution, and high-level disagreement in traditional uses corroborates the significance of this study. Being the first list on medicinal flora of Shigar valley, the present study offers baseline data for researchers, mostly interested in high mountains Phyto-diversity and related traditional knowledge. The sub-alpine species in environs are possible for conservation and cultivation [31-33].

The findings of the present study were also compared with previous studies conducted in the Himalayas of India, China, and Nepal, which showed that only a few plant species were similar which include: Allium carolinianum, Allium cepa, Artemisia scoparia, Berginia stracheyi, Hippophe rhamnoides and Thymus linearis to India, China and Nepal. These outcomes might be related to the floristic and cultural resemblance, since similar to Baltistan; Ladakh is also the home of Balti and Brokpa groups [34,35], which have comparable traditional knowledge on adjacent plant biodiversity. Furthermore, due to comparable climatic, topographic, and edaphic conditions; the flora of the study area shares several species with Ladakh, Jammu, and Kashmir state of India [36].

Fruits and leaves of Hippophe rhamnoides subs. Turkestanica is used in the treatment of gastrointestinal syndromes and skin diseases. Similar species have been described to treat cardiac diseases, cancer and stomach ache in Haramosh and Gilgit valleys-Gilgit [28]. Similarly, in the Ladakh district of India, this plant is used to treat gynecological disorders such as unbalanced menstrual cycles, amenorrhea or dysmenorrhoea [37], and to increase digestion [38]. Pimpinella diversifolia is among the most common medicinal herbs in the study area, which is used for abdominal disorders, fever, and blood purification. In the Lesser Himalayan region of Pakistan and Lao PDR, this species is used to alleviate gas problems and indigestion [15,38]. The inhabitants of Swat Valley use Artemisia scopariato treat abdominal worms [39]. Similar species have been described as purgative in Gujarat Pakistan [25] and an effective remedy against the hyper-acidic stomach in Zhejiang province, China [40].

The richness of medicinal plant species in the study area could improve the economic status of local communities by marketing and sustainable consumption. Residents can make their home gardens or micro park system of medicinally important species on their land. However, illiteracy and lack of developmental packages are the major handicaps in the operation of such implications.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the population of the study area is very well familiar with plant diversity and now the use of these alleviative medicinal plants has been continued alike to the civic level. It has become an accepted analysis for their ailments on the one duke and additionally serves the purpose of their accustomed claim of food, fodder, shelter, fuel wood, and timber.

Author Contributions

T.G. conceived the research. S.U. (Saif Ullah) conceptualized the idea and designed the experiment. S.U. (Saif Ullah) performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript with the contribution of M.Z. and L.J. Y.K. and S.U. (Shakir Ullah) reviewed and edited the manuscript and provide their intellectual insights.

Funding

This study was supported by the College of economic and management northeast forestry university Harbin China.

Acknowledgments

We thank Central Karakoram National Park and staff for helping in data collection.

REFERENCES

- Körner C, Spehn EM. Mountain biodiversity: A global assessment, Parthenon Pub. Group, Boca Raton, USA. 2002;14:336.

- Veith C, Shaw J. Why invest in sustainable mountain development? 2011.

- Abbas Z, Khan SM, Abbasi AM, Pieroni A, Ullah Z, Iqbal M, et al. Ethnobotany of the Balti community, Tormik Valley, Karakorum Range, Baltistan, Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12(1):1-38.

- Webster GL, Nasir E. The vegetation and flora of the Hushe Valley (Karakoram Range, Pakistan). Pakistan J Forestry. 1965;15(3).

- Afridi BG. Baltistan in history. 1988: Emjay Books International.

- Hussain I, Bano A, Ullah F. Traditional drug therapies from various medicinal plants of central Karakoram National Park, Gilgit-Baltistan Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2011;43:79-84.

- Bano A. Quantitative ethnomedicinal study of plants used in the skardu valley at high altitude of Karakoram-Himalayan range, Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10(1):1-43.

- Khan SM, Ahmad H, Ramzan M, Jan MM. Ethnomedicinal plant resources of Shawar Valley. Pakistan journal of biological sciences: PJBS. 2007 May;10(10):1743-1746.

- Gerique A. An introduction to ethnoecology and ethnobotany: Theory and methods. Integrative assessment and planning methods for sustainable agroforestry in humid and semiarid regions. Advanced Scientific Training (ed.). Loja, Ecuador. 2006.

- Lulekal E, Kelbessa E, Bekele T, Yineger H. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Mana Angetu District, South-Eastern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4(1):1-10.

- Cotton CM, Wilkie P. Ethnobotany: principles and applications. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1996.

- Martin GJ. Ethnobotany: A methods manual. Springer; 2014.

- Delcourt PA, Delcourt HR. The influence of prehistoric human-set fires on oak-chestnut forests in the southern Appalachians. Castanea. 1998;1:337-345.

- Takhtajan A, Crovello TJ, Cronquist A. Floristic regions of the world. Berkeley: University of California Press, USA; 1986.

- Abbasi AM, Khan MA, Shah MH, Shah MM, Pervez A, Ahmad M. Ethnobotanical appraisal and cultural values of medicinally important wild edible vegetables of Lesser Himalayas-Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9(1):1-66.

- Shah GM. Traditional uses of medicinal plants against malarial disease by the tribal communities of Lesser Himalayas–Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol, 2014;155(1):450-462.

- Ali SI, Qaiser M. A phytogeographical analysis of the phanerogams of Pakistan and Kashmir. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Section B: Biological Sciences. 1986;89:89-101.

- Hanson CR. The northern suture in the Shigar valley, Baltistan, northern Pakistan. Geological Society of America Special Paper. 1989;232:203-215..

- Waldtmann C, Kreutzmann H, Schollwöck U, Maisinger K, Everts HU. Ground states and excitations of a one-dimensional kagomé-like antiferromagnet. Physical Review B. 2000;62(14):9472.

- IUCN S. Antelope Specialist Group 2008. Connochaetes taurinus, 2008.

- Abbas Z, Khan SM, Alam J, Khan SW, Abbasi AM. Medicinal plants used by inhabitants of the Shigar Valley, Baltistan region of Karakorum range-Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13(1):1-5.

- Schemnitz SD. Wildlife management techniques manual. Wildlife Society; 1980.

- Wilson E. The sphinx in the city: Urban life, the control of disorder, and women. Univ of California Press. 1992.

- Bano A, Ahmad M, Zafar M, Sultana S, Rashid S, Khan MA. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of the most commonly used plants from Deosai Plateau, Western Himalayas, Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan. Journal Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155(2):1046-1052.

- Hussain K, Nisar MF, Majeed A, Nawaz K, Bhatti KH. Ethnomedicinal survey for important plants of Jalalpur Jattan, district Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. Ethnobot Leaflets. 2010;7:1-11.

- Khan M. Plant species and communities assessment in interaction with edaphic and topographic factors; an ecological study of the mount Eelum District Swat, Pakistan. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 2017. 24(4): p. 778-786.

- Khan KU, Shah M, Ahmad H, Khan SM, Rahman IU, Iqbal Z, et al. Exploration and local utilization of medicinal vegetation naturally grown in the Deusai plateau of Gilgit, Pakistan. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25(2):326-331.

- Khan SW, Khatoon SU. Ethnobotanical studies on useful trees and shrubs of Haramosh and Bugrote valleys in Gilgit northern areas of Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2007;39(3):699-710.

- Khan SW, Khatoon SU. Ethnobotanical studies on some useful herbs of Haramosh and Bugrote valleys in Gilgit, northern areas of Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2008;40(1):43.

- Klimes L. Life-forms and clonality of vascular plants along an altitudinal gradient in E Ladakh (NW Himalayas). Bas Appl Ecol. 2003;4(4):317-328.

- Schippmann U, Leaman DJ, Cunningham AB. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: global trends and issues. Biodiversity and the ecosystem approach in agriculture, forestry and fisheries. 2002.

- Shinwari ZK, Qaiser M. Efforts on conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants of Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2011;43(1):5-10.

- Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Morales R. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Botanical J Lin Soc. 2006;152(1):27-71.

- Bhasin V. Ecology and health: A study among tribals of Ladakh. Studies of Tribes and Tribals. 2005;3(1):1-3.

- Zeisler B. On the position of Ladakhi and Balti in the Tibetan language family. Ladakhi Histories: Local and Regional Perspectives. Leiden, Boston: Brill. 2005.

- Klimeš L, Dickoré B. A contribution to the vascular plant flora of Lower Ladakh (Jammu & Kashmir, India). Willdenowia. 2005;1:125-153..

- Chaurasia OP. Herbal formulations from cold desert plants used for gynecological disorders. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2011;9:59-66.

- De Boer H, Lamxay V. Plants used during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum healthcare in Lao PDR: A comparative study of the Brou, Saek and Kry ethnic groups. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5(1):25.

- Hamayun M, Afzal S, Khan MA. Ethnopharmacology, indigenous collection and preservation techniques of some frequently used medicinal plants of Utror and Gabral, district Swat, Pakistan. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2006;3(2):57-73.

- Chaudhary MI, He Q, Cheng YY, Xiao PG. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants from tian mu Shan biosphere reserve, Zhejiang-province, China. Asian J Plant Sci. 2006.

Citation: Ullah S, Zaman M, Jiaqi L, Khan Y, Ullah S, Gang T (2020) Quantifying the Estimation and Abundance of Plant Diversity of Shigar Valley, Gilgit -Baltistan, Pakistan. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 11:522. doi: 10.35248/2157-7471.20.11.522.

Copyright: © 2020 Ullah S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.