Indexed In

- Academic Journals Database

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

- Scimago

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- MIAR

- University Grants Commission

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2023) Volume 14, Issue 3

Post-Vaccine SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection and Associated Factors among Health Care Providers with Pre-Vaccination Infection History in Addis Ababa Public Hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022

Enyew Belay*Received: 07-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. JVV-22-18245; Editor assigned: 10-Oct-2022, Pre QC No. JVV-22-18245 (PQ); Reviewed: 21-Oct-2022, QC No. JVV-22-18245; Revised: 23-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. JVV-22-18245 (R); Published: 01-Mar-2023

Abstract

Background of the study: The protection against Corona virus diseases 2019 variants by preexisting antibodies elicited due to the current vaccination or natural infection is a global concern. Even though studies are not found as per the investigators’ scope in Ethiopia case reports show that’s a significant number of health professionals are reported to get re-infected after vaccination. Nevertheless, there are more studies which revealed the symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 re-infection rate and associated factors elsewhere in Ethiopia, and in particular amongst healthcare providers actively engaged in Addis Ababa public health facilities.

Objective: This study has aimed at assessing the magnitude of post vaccine reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and associated factors among health care providers with history of pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 G.C

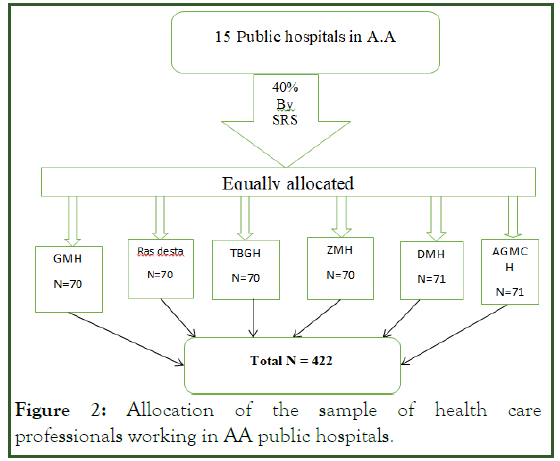

Methods: Facility based cross-sectional study was conducted from July 11 to July 30, 2022. A total of 422 health professionals were included. First simple random sampling method was employed to select 40% of the total hospitals. Then the total sample size was equally allocated to each selected hospital then after each individual was selected purposely. The data was collected using structured self-administered questionnaire. The analysis was done by using SPSS version 26.0 and for data entry EPi info version 7.1 was used. Both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to determine p value.

Results: The finding of this study revel that the magnitude of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and associated factors among health care providers with history of pre-vaccination infection history is 60 (14.4%) (95% CI 10.8-17.9). In multivariable analysis, health care Professionals who took IP training on COVID-19 (AOR=7.177: CI=4.761-9.698), chronic respiratory diseases (AOR=3.029: CI=2.406-9.133), health professionals who took third dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (AOR=1.75: CI=1.14-2.68) and being a midwife had statically significant.

Conclusion and recommendation: This study showed the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history was high, IP training on COVID-19, educational status, profession, type of vaccine up taken in 1st dose, chronic respiratory diseases, number of vaccination status were significantly associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection after vaccination. Giving infection prevention training, encouraging taking the vaccine as protocol and using proper personal protective equipment is recommended.

Keywords

Post vaccine infection; SARS-CoV-2; Health care providers; Pre-vaccination infection history; Public hospitals

Abbrevations

AGMCH: Abebech Gobena Maternity and Child Hospital; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; BMI: Body Mass Index; CDC: Centers for Disease Control; CI: confidence Interval; COR: Crudes Odds Ratio; COVID 19: Coronavirus disease 2019; DMRH: Dagmawi Minilik Referral Hospital; GMRH: Gandhi Memorial Referral Hospital; HCW: Health Care Workers; IP: Infection Prevention; OR: Odds Ratio; SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; SPSS: statistical Package for Social Sciences; ST. POUL RH: Sent poul Referral Hospital; TBGH: Tirunesh Beijing General Hospital; WHO: World Health Organization; ZMRH: Zewditu Memorial Referral Hospital; AGMCH: Abebech Gobena Maternity and Child Hospital

Introduction

Background of the study

Several cases of COVID-19 reinfections have been reported worldwide, Coronavirus disease is defined as an infectious disease caused by a novel coronavirus now called Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The first human cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel Coronavirus causing COVID-19, subsequently named SARSCoV- 2 were first reported by officials in Wuhan City, China, in December 2019. SARS-CoV-2 was identified in early January and its genetic sequence shared publicly on 11-12 January [2].

The full genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 from the early human cases and the sequences of many other viruses isolated from human cases from China and all over the world since then show that SARS-CoV-2 has an ecological origin in bat populations. All available evidence to date suggests that the virus has a natural animal origin and is not a manipulated or constructed virus. Many researchers have been able to look at the genomic features of SARS-CoV-2 and have found that evidence does not support that SARS-CoV-2 is a laboratory construct [3]. Globally there are 477,312,339 corona virus cases, of which 6,130,808 deaths and 412,392,494 cases were recovered [4]. There are also 109,555 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Asia, 8,658 in Africa, 332,866 in North America, 20,269 in South America, 568,894 in Europe, 5,051 in Australia and 1,045,403 in the whole world.

Danish epidemiologists were excited in February when they first saw how well the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine was working in health-care workers and residents of long-term care facilities, who were the first to receive it in Denmark. A clinical trial-1 in more than 40,000 people had already found the vaccine to be 95% effective in protecting recipients from symptomatic COVID-19. But some scientists were among the first to test its effectiveness outside clinical trials, which can exclude some unhealthy individuals or those taking medicines that suppress immune responses [5].

For COVID-19, the ultimate goal is global herd immunity, with natural infection and vaccination being the two main pathways to herd immunity. Preliminary data reveal exceptionally encouraging vaccine protection results after six months of mass vaccination efforts against SARS-CoV-2. While some countries have vaccinated more than half of their populations, many others are lagging [6].

Reducing reinfection is crucial, given the high global rate of infection, particularly with new variations, and the slow pace of immunization. Examining reinfection, particularly the persistence of protection following natural infection, or natural immunity, will help us better understand the prospects for herd immunity, which is predicated on the idea that natural infection develops sufficient, protective immunity [7]. The major goal of this study is to assess the prevalence of COVID-19 symptomatic reinfection and associated factors among vaccinated health care providers in Addis Ababa public hospitals.

Statement of the problem

Globally, there are about 477,312,339 cases and about 6,130,808 deaths of SARS-CoV-2 with affecting about 225 countries and territories. Ethiopia reported an index case on March 13, 2020, and there were 348,669 cases and 5722 deaths in the country as of October 3, 2021. SARS-CoV-2 immunizations has emerged, and currently 22 vaccinations have been approved for use, in addition to effective public health measures such as education, social distance, wearing face masks, hand washing, and avoiding crowded settings. As a result, until October 4, 2021, around 47 percent and 35 percent of the world's populations were partially and fully vaccinated for COVID-19, respectively. Ethiopia received the first 2.2 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine from the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility, with plans to vaccinate 20% of the population by the end of 2021 [8].

Vaccine uptake refers to the number of persons that received a specific dose of a vaccine in a given time period, which can be stated as an absolute number or as a percentage of the target population. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designated Health Care Workers (HCWs) as a demographic at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and phase 1 allocation of COVID-19 vaccine targeted HCWs to protect themselves and the public. Furthermore, health professionals are a reliable source of public health information, and their role in increasing COVID-19 vaccination uptake is critical [9].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) evaluates data from many trials on a regular basis to determine how well SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations function in the real world among all persons who are eligible for vaccination. SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations are still helpful in avoiding severe COVID-19 disease, including hospitalization, according to these trials [10]. But infections caused by vaccines are likely to occur. Most infections can be prevented with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. They are not, however, 100 percent efficient. On the other hand, COVID-19 reinfection occurred at a rate of 0.35 occurrences per 1,000 person-days, with individuals working in COVID clinical and clinical units having 3.77 and 3.57 times the risk of reinfection, respectively, compared to those working in non-clinical units. COVID-19 recurrence had a rate of 1.47 instances per 1,000 person-days [11]. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection has only been recorded seldom in the literature and Even though studies are not found as per the investigators’ scope in Ethiopia or Africa. But some cases are admitted in some Hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with verified recurring SARS-CoV-2 illness [12].

Significance of the study

Understanding COVID-19 reinfection among health care providers and the magnitude of reinfection is essential for identifying epidemiological aspects of infection and for applying control measures at the local, state, and federal levels as well as for preventing and containing the spread of the infection.

Even though the investigator is unable to find studies done in Ethiopia, some case reports show that’s a significant number of health professionals by SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination. Knowing the prevalence of COVID-19 reinfection helps for the health professionals to take a care on COVID-19 prevention protocols even if weather they are vaccinated or not.

The finding of this study will provide information on the current status of SARS-CoV- 2 symptomatic reinfection among vaccinated health care providers and baseline data for future planning and interventions for stakeholders and policy makers. The finding of this study may also be used to provide vaccination improvement program supporters and implementers.

Hence, this study will provide insight about SARS-CoV-2 reinfection after vaccination with pre-vaccination infection history in government hospitals vaccinated health care providers under the capital city and can be used as an input for similar studies that are going to be conducted in the future and it also provides the new and the current aspect of SARS-CoV-2 symptomatic infection in vaccinated health care providers within the study area.

Overviews of SARS-CoV-2 post vaccine symptomatic infection: Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Virus) is an occurrence of infection by COVID 19 either after vaccination or previously exposure to the virus. The effectiveness and persistence of immune responses in protecting the host against reinfection are still unknown. Several countries have reported mild to severe sickness as a result of reinfection. For some viruses, the first infection can provide lifelong immunity whereas the other is only temporary [13]. According to a study in United Kingdom about 80% of persons with coronavirus sickness are asymptomatic or only have mild flu symptoms, which may be treated at home or in isolation facilities to stop the virus from spreading. 15% of people get severe symptoms that necessitate hospitalization [14].

Several vaccine platforms have been licensed for emergency use worldwide, most of which provide a high degree of protection from disease and hospitalization [15]. However, the degree of protection from infection is still controversial. In a study investigating the correlation between previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and BNT162b2 vaccine-induced immune responses (i.e., humoral and T cell responses), individuals with prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 exhibited more robust humoral and cellular responses compared to infection-naïve individuals (i.e., not infected previously with SARS-CoV-2). Upon administrating one dose of the vaccine, individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection generated significantly higher anti-S titers than infection-naive individuals, which potentially implies that one dose may be sufficient for those previously infected [16,17].

Due to their frequent contact to highly infectious settings, healthcare personnel are one of the groups most susceptible to contracting SARS-CoV-2. Numerous COVID-19 issues have led to the deaths of thousands of front-line doctors and healthcare workers, with the bulk of these deaths taking place in low- and middle-income countries [18].

The incidence of COVID-19 reinfection is challenging to document, as the extensive resources necessary to confirm reinfection have not been available or practical to employ clinically confirmation of reinfection requires multiple Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) tests, viral cultures, lab testing, and collection of clinical symptoms and epidemiological risk factors. As evidence based on these inaccessible resources was necessary for formal reporting of COVID-19 reinfection, this has likely resulted in under-reporting of reinfection in scientific journals.

Socio-demographic related factors

A descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in Tanta University hospitals in Egypt found a significant link between the prevalence of problems and the age range of 40-58 years significantly related to reinfection. The incidence of COVID-19 infection among the examined nurses showed that more than one third of them had experienced one attack, fewer than onequarter had experienced two or three attacks, and only (1.7%) had experienced four.

According to the current meta-analysis study, age, gender, time of reported relapse after initial infection and persistent COVID-19 positive Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) results were all examined in these studies. Cases of clinical relapse are documented 34 (mean) 10.5 days after full recovery following the first episode of infection. Positive COVID-19 PCR testing results remain in patients with clinical relapse for up to 39 days after initial positive testing. Positive testing was reported for patients who did not have a clinical recurrence for up to 54 days. After a 70 days period following the original infection, there were no reports of symptomatic reinfections [19].

A cross-sectional study on socio-demographic and Clinical Features of COVID-19 reinfection cases among health care Workers in Turkey which declares the symptoms did not differ significantly between the two courses, 73.9 percent were treated as outpatients during the first illness, while all but one (95.7%) was treated as outpatients during the second. It took an average of 106 days between infections. None of the individuals had to be treated in an intensive care unit since they were free of illness.

Rates of infection with SARS-CoV-2 according to the vaccination status

Infection with other human coronaviruses is common, despite the presence of antibodies. The current case series indicate that COVID-19 reinfection is possible, and the second infection may result in worse. Recent research found that full vaccination was effective against SARS-CoV-2, even for developing strains, and that infection rates were much lower among vaccinated people than among non-vaccinated people. In comparison to Wuhan (B.1) or Alpha (B.1.1.7) variants, multiple investigations found inadequate vaccination effectiveness against the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant. Another study from a Massachusetts town found that 74 percent of 469 cases, predominantly infected with the Delta strain, were fully vaccinated. In contrast, data from densely populated and low vaccine coverage regions is limited. Another study identified a tiny fraction of vaccine breakthrough infections in the United States; however, data from densely populated and low vaccine coverage regions is limited. As a result, it's critical to assess the vaccine's efficacy against new variations.

On the other study 381 symptomatic employees presented specimens for SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR testing between May 1 and July 31, 2021; of those, 115 (30.2%) received at least one dose and 96 (25.2%) received full doses of COVISHIELDTM vaccine before the test date. A 37 (38.5%) of full-dose vaccinated people were infected with the virus.

Effect of chronic medical illness and doses of vaccination related factors

According to a study done in New Delhi, in India on Breakthrough COVID-19 infections after vaccinations in healthcare and other workers in a chronic care medical facility conducted cross sectional. The second dose was completed by 107 (94.7%) people, while the first dose was completed by 6 people (5.3 percent). After receiving any dosage of the vaccination, 19 people (16.9%) developed symptoms of COVD-19. In 15 people, symptomatic breakthrough infections occurred more than 14 days after the second dosage (13.3%). All 14 had minor COVID-19 illness, with the exception of one (who required hospitalization).

According to the prospective cohort study involving health care workers (≥18 years of age) in the United Kingdom, Adjusted vaccine effectiveness decreased from 85 percent (95 percent Confidence Interval (CI), 72 to 92) 14 to 73 days after the second dose to 51 percent (95 percent CI, 22 to 69) at a median of 201 days (interquartile range, 197 to 205) after the second dose in previously uninfected participants who received longinterval BNT162b2 vaccine; this effectiveness did not differ significantly between long-interval and short-interval BNT162b2 vaccine recipients Adjusted vaccination effectiveness among ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine recipients was 58 percent (95 percent CI, 23 to 77) at 14 to 73 days following the second dose, which was significantly lower than that of BNT162b2 vaccine recipients. Unvaccinated participants' infection-acquired immunity declined after a year, but was consistently higher than 90% in those who were vaccinated later, even in those who had previously been unvaccinated.

Other factors related to SARS-CoV-2 reinfection

According to a study in health care workers in the United Kingdom the population uptake of two doses of COVID-19 vaccines in the United Kingdom (in persons >12 years of age) as of February 2022 was 84.5% of which 210 participants were reinfected after 6 months of vaccination.

Individuals who recovered from COVID-19 were generally thought to generate a robust immune response to clear the virus. However, it remains to be determined whether the initial infection confers a protective immunity to subsequent infections. Despite the existence of antibodies, reinfection with other human coronaviruses happens often. According to the most recent case studies, COVID-19 reinfection is a possibility. In almost 20% of patients, the second infection may worsen their symptoms, and those who are old or immunecompromised may experience catastrophic problems.

In a larger cohort study analyzing reinfection rates in Qatar, most of the patients were asymptomatic or experienced mild symptoms after reinfection. In this study, which included 133,266 laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases, 54 out of 243 positive cases (22.2%) showed a high reinfection (i.e., tested positive ≥ 45 days following the first positive test), out of which four reinfections were confirmed through viral genome sequencing [17]. Several risk factors are associated with COVID-19 reinfection, such as being a health care worker, a blood-group A person, or having low antibody (IgG) titers.

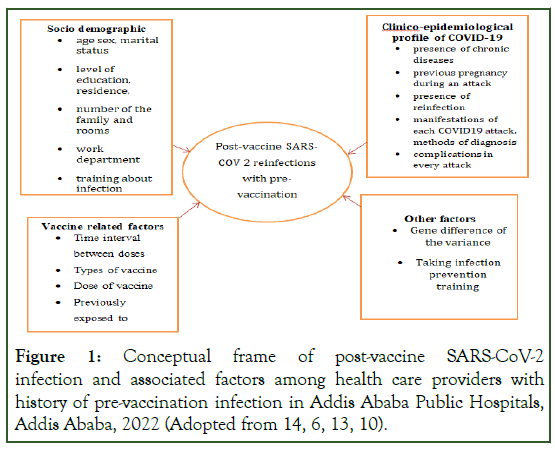

Conceptual frame work of post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated factors among health care providers with prevaccination infection history (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual frame of post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated factors among health care providers with history of pre-vaccination infection in Addis Ababa Public Hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (Adopted from 14, 6, 13, 10).

Objective

General objective: To assess the magnitude of post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and associated factors among health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022.

Specific objectives: To determine the magnitude of post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among health care providers with prevaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022.

To identify the factors associated with post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 reinfection health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The research was conducted in Addis Ababa's public hospitals. The city has a population density of 5,535.8 inhabitants per square kilometer and occupies an estimated area of 174.4 square kilometers. According to estimates from Ethiopia's Central Statistical Agency, the Addis Ababa Region's total population is estimated to be 3.55 million in 2007. Females in the reproductive age group account for 35.5 percent of the overall population. There are 11 sub-cities and 116 woreda in the region. Eight hospitals are operated by the Addis Ababa Health Bureau, seven by the Federal Ministry of Health, one by Addis Ababa University, three by non-governmental organizations, three by the military and police forces, and 34 by owners who are private. There are about 700 private clinics, with 75 of them being higher clinics, and 116 public health centers.

Study design and period

Institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted from July 11 To July 30, 2022.

Source populations

All health care professionals who are vaccinated at least once for SARS-CoV-2 and had history of infection before vaccination working in Addis Ababa's public hospitals.

Study population: A health care professional who are vaccinated at least once for SARS-COV 2 and had history of infection before vaccination working randomly selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, in 2022.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: All health care professionals who are vaccinated at least once for COVID 19 and had history of infection before vaccination working in Addis Ababa's public hospitals those present during the data collection period.

Exclusion criteria: Those health care professionals who were on different leave during data collection period and those health care professionals who are severely ill were excluded.

Sample size and sampling technique

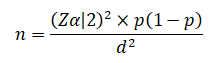

Sample size: To get the maximum sample size, previous proportion was considered as 50%. Therefore, the required sample size of the study was determined by single population proportion formula as the following.

Where n is the required sample size

Zα/2 is the standardized normal distribution value at the 95% confidence interval level, which is 1.96.

p is the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection, which is 50% d is the margin of error, which is set to 5%.

After adding 10% non-response rate total sample size was 422

Sampling technique: Since there are about 15 public hospitals in Addis Ababa, first simple random sampling method was employed to select 40% of the total hospitals. Then the total sample size was equally allocated to each selected hospital then after each individual was selected purposely. The participants were selected by asking two questions, the first question was ‘have you been infected by SARS-CoV-2 and then those who said ‘yes’ were asked ‘have you been ever vaccinated for SARSCoV- 2 those who answered ‘yes’ in both questions were selected to participate in this study (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Allocation of the sample of health care professionals working in AA public hospitals.

Study variables

Dependent variables: Post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 infections with pre-vaccination infection history.

Independent variables: Socio demographics: Like age, sex, weight, BMI, work experience in years, professional category, income, working area/department.

Vaccine related: such as time interval between doses, types of vaccine, dose of vaccine, previously exposed to COVID.

Clinico-epidemiological profile: Presence of chronic diseases, previous pregnancy during an attack, presence of reinfection, manifestations of each COVID-19 attack, methods of diagnosis, complications in every attack

Other factors: Gene difference of the variance, taking infection prevention training.

Operational definition

SARS-CoV-2: Is an illness caused by a novel coronavirus now called severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2.

Vaccinated: the time after health care providers take at least one dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

Vaccinated health care provider: Those health care providers who are vaccinated at least one doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Post-vaccine SARS-CoV-2 reinfection with pre-vaccination infection history: Defined as positivity for SARS-CoV-2 either PCR or a rapid antigen test before taking COVID-19 vaccines and then confirmed positive after taking at least one dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Vaccine: Is a product that stimulates a person’s immune system to produce immunity to a specific disease, protecting the person from that disease.

Data collection tool

A pretested, structured interview questionnaire consisting of items with predetermined response categories was utilized to collect data. The questionnaire was modified based on the findings of the literature review. The tool has four sections:

• First section consists of socio demographic characteristics.

• Second section consists of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine status related questions.

• Third section is about Clinico-epidemiological profile of SARS-CoV-2.

• Fourth is infection prevention related factors. The questionnaire was designed in English.

Data collection procedures

Five BSC (two nurses, two midwives and one health officer) health care staffs were involved in data collection. The data collectors were given one day training prior to data collection, with a supervisor checking the completeness, accuracy, and appropriateness of the data collected every day then the data collectors were supervised on the objectives, benefits of the study, individual‘s right and informed consents on the questionnaire.

Data quality control

A pre-test of the questionnaire was performed on 5% of health-care staff in Yarer general hospital. Data was obtained after each health care professional has given their informed consent. A code was used to preserve confidentiality, and no names of respondents were used in any of the data collection instruments. The collected data was reviewed and checked for completeness.

Data analysis procedure

First the collected data was checked for incompletion and misfiled. Then the data was cleaned and stored for consistency and entered in to Epinfo version 7.1, and then it was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 software for analysis. Descriptive statistics like frequency, proportion, mean, and standard deviation was computed to describe study variables in relation to the population. Then this result was compiled and presented using texts, tables, graphs and pie-charts. Logistic regression (bivariable and multivariable) was used to determine the effect of independent variables on the outcome variables. Variables found to have a P-value<0.2 in the binary logistic regression was entered/exported into multivariable analysis to identify their independent effects and then strength of association was declared at P value<0.05. Then after, the final results were presented as Odds Ratio (AOR).

Results and Discussion

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

Out of 422 study participant 418 respondents participated in this study making a response rate of 99.05%. About 51.7% of health professionals were females. The mean age of the respondents were 33.7 years with standard deviation +7.36. Most participants of this study 61.5 % (257) are under the age 25-34. About 227(54.3%) participants in this study were BSC in their qualification and 101(24.2%) nurses. And also, one hundred seventy-one (40.9%) participants in this study were serviced five years and below. Regarding the BMI of participants about 202 (48.3%) was in normal range (Table 1).

| Variable | Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 202 | 48.3 |

| Female | 216 | 51.7 | |

| Age category | ≤ 24 | 17 | 4.1 |

| 25-34 | 257 | 61.5 | |

| 35–44 | 106 | 25.4 | |

| 45 and above | 38 | 9.1 | |

| Marital status | Single | 168 | 40.2 |

| Married | 210 | 50.2 | |

| Widowed | 15 | 3.6 | |

| Divorced | 25 | 6 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 233 | 55.7 |

| Muslim | 73 | 17.5 | |

| Protestant | 61 | 14.6 | |

| Catholic | 40 | 9.6 | |

| Others | 11 | 2.6 | |

| profession | Health officer | 17 | 4.1 |

| Nurse | 101 | 24.2 | |

| Laboratory Technician | 24 | 5.7 | |

| Midwife | 93 | 22.2 | |

| Doctor | 63 | 15.1 | |

| Physiotherapist | 69 | 16.5 | |

| Pharmacist | 32 | 7.7 | |

| Others | 20 | 4.8 | |

| Qualification level | Diploma | 93 | 22.2 |

| BSc | 227 | 54.3 | |

| MSc and above | 98 | 23.4 | |

| Total service year | ≤ 5 years | 171 | 40.9 |

| 6-10 years | 127 | 30.4 | |

| ≥ 11 years | 120 | 28.7 | |

| BMI | Under weight | 34 | 8.1 |

| Normal weight | 202 | 48.3 | |

| Over weight | 123 | 29.4 | |

| Obesity | 59 | 14.1 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of SARS CoV-2 reinfection among vaccinated health care providers with prevaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (N=418).

SARS-CoV-2 reinfection exposure status of the study participants

Regarding the exposure status of the study participants, about 188 (45%) health care providers had contact with SARS-CoV-2 patients either in hospital or in the family. More than half 309 (73.9%) give a care for SARS-CoV-2 patients. 31 (7.4%) participants have confirmed chronic illness like DM 12 (2.9), HTN 7 (1.7%) and chronic respiratory diseases 13 (3.1%) (Table 2).

| Variable | Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact with SARS-CoV-2 patients either in hospital or in the family | Yes | 188 | 45% |

| No | 230 | 55% | |

| Taking care of SARS-CoV-2 patients | Yes | 309 | 73.9 |

| No | 109 | 26.1 | |

| Frequency of contact | Every day | 107 | 25.6 |

| Once per week | 137 | 32.8 | |

| Once per month | 65 | 15.6 | |

| Never | 88 | 21.1 | |

| Confirmed chronic illness | Yes | 31 | 7.4 |

| No | 387 | 92.6 | |

| DM | Yes | 12 | 2.9 |

| No | 406 | 97.1 | |

| HTN | Yes | 7 | 1.7 |

| No | 411 | 98.3 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | Yes | 13 | 3.1 |

| No | 405 | 96.9 | |

| Working area | Office/non-clinical | 9 | 2.2 |

| Ambulance | 19 | 4.5 | |

| OPD | 68 | 16.3 | |

| Labor and delivery ward | 34 | 8.1 | |

| Laboratory and imaging area | 43 | 10.3 | |

| Emergency | 124 | 29.7 | |

| Inpatient ward | 68 | 16.3 | |

| ICU | 24 | 5.7 | |

| OR | 21 | 5 | |

| Others | 8 | 1.9 |

Table 2: SARS-CoV-2 reinfection exposure status among vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (N=418).

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status of the study participan

Most participants of the study 200 (47.8%) took AstraZeneca in their first vaccination. And also about 321 (76.8%) participants take the second dose of the vaccines as shown in the Table 3.

| Variable | Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of vaccine up taken in 1st dose | Pfizer/BioNTech | 64 | 15.3 |

| Janssen (Johnson and Johnson) | 154 | 36.8 | |

| AstraZeneca | 200 | 47.8 | |

| Duration of 1st dose uptake | Between 6–9 months back | 44 | 10.5 |

| Between 9–12 months back | 132 | 31.6 | |

| Between 12-15 months back | 133 | 31.8 | |

| 15 months and long back | 109 | 26.1 | |

| 2nd dose of vaccine up taken | Yes | 321 | 76.8 |

| No | 98 | 23.2 | |

| Type of vaccine up taken in 2nd dose | Pfizer/BioNTech/Sinopharm | 73 | 22.74 |

| Janssen (Johnson and Johnson) | 128 | 39.88 | |

| AstraZeneca | 120 | 37.38 | |

| Time interval between 1st dose and 2nd of vaccine | Three months after the first dose | 46 | 14.3 |

| 6th month after the 1st dose | 119 | 28.5 | |

| Above 6th months | 156 | 37.3 | |

| 3rd dose of vaccine up taken (booster) | Yes | 21 | 5 |

| No | 397 | 95 |

Table 3: SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status of vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (N=418).

COVID-19 reinfection and infection prevention related status of the study participants

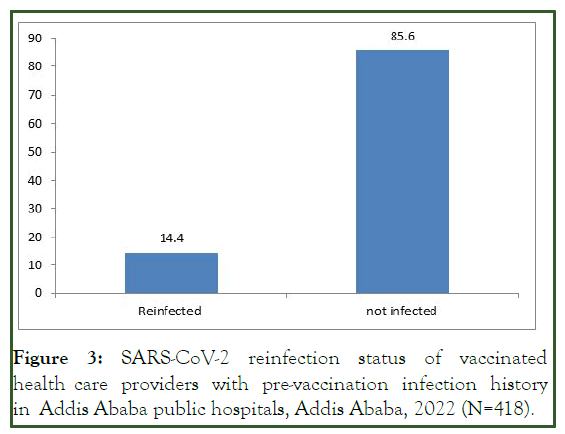

About 60 (14.4%) (95% CI 10.8-17.9), of participants were reinfected by SARS-CoV-2 after vaccination of at least one dose of the vaccine. Most of them 51 (85%) are diagnosed by rapid antigen test. And there is no hospitalization in those who are reinfected. Regarding the infection prevention, 306 (73.2%) of participants took the training (Table 4 and Figure 3).

| Variable | Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reinfected by SARS-CoV-2 after vaccination | Yes | 60 | 14.4 |

| No | 358 | 85.6 | |

| How it was diagnosed | Molecular testing | 9 | 15 |

| A rapid antigen test | 51 | 85 | |

| When infected after last vaccines | Less than 3 months | 0 | 0 |

| Three months and above | 60 | 100% | |

| Hospitalizations | Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 60 | 100 | |

| IP training on COVID-19 | Yes | 306 | 73.2 |

| No | 112 | 26.8 | |

| How often wear PPE | Always | 260 | 37.8 |

| Sometimes | 158 | 62.2 |

Table 4: SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and infection prevention related status of vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (N=418).

Figure 3: SARS-CoV-2 reinfection status of vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (N=418).

Bivariable and multivariable analysis of Factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection

In this study bivariable analysis, taking an IP training (COR=6.629, CI=3.696-11.888), educational status (diploma) (COR=3.150, CI=1.263-7.855), profession (being midwife) (COR=4.917, CI=1.175-20.581), type of vaccine up taken in 1st dose (taking Janssen/Johnson and Johnson) (COR=2.346, CI=1.221-4.508) and those health care professionals who have chronic respiratory diseases (COR=5.571: CI=1.804-17.203) significant and exported into multivariable analysis in order to control confounders whereas, BMI, taking care/treating COVID-19 patients and experience not significant with the SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

In multivariable analysis, those predictors which showed statistical significance in bivariable analysis and p value less than 0.2 were used to run multivariable analysis. In multivariable analysis, health care Professionals who took IP training on COVID-19 were significantly associated to professionals who did not took IP training (AOR=7.177: CI=4.761-9.698). The ODDs of health care professionals who has chronic respiratory diseases were significantly associated with those who had no history of chronic respiratory diseases (AOR=3.029: CI=2.406-9.133). Regarding the vaccination status, health professionals who took only the first dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were significantly associated to professionals who took the 3rd booster doses (AOR=1.75: CI=1.14-2.68) (Table 5).

| Variable | SARS-CoV-2 reinfection | 95% CI | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | COR | AOR | |||

| IP training on COVID-19 | Yes | 284 | 22 | 6.629 (3.696-11.888)* | 7.177 (4.761-9.698)** | 0.001 |

| No | 74 | 38 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational status | Diploma | 7 | 86 | 3.150 (1.263-7.855)* | 3.500 (1.265-9.682)** | 0.016 |

| BSC | 33 | 194 | 1.507 (0.815 – 2.787) | 2.010 (0.960-10.754) | ||

| MSc and above | 20 | 78 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Profession | Health officer | 3 | 14 | 1.556 (0.312-7.751) | 2.288(0.341-15.352) | |

| Nurse | 18 | 83 | 1.537 (0.495-4.773) | 2.738 (0.697-10-754) | ||

| Laboratory technician | 2 | 22 | 3.667 (0.627-21.446) | 10.401 (1.309-14.653) | ||

| Midwife | 4 | 59 | 4.917 (1.175-20.581)* | 9.315 (1.814-17.826)** | 0.008 | |

| Doctor | 11 | 82 | 2.485 (0.755-8.183) | 4.774 (1.149-19.826) | ||

| Physiotherapist | 11 | 57 | 1.727 (0.520-5.737) | 3.392 (0.812-14.164) | ||

| Pharmacist | 6 | 26 | 1.444 (0.376-5.551) | 3.477 (0.708-17.059) | ||

| Others | 5 | 15 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Type of vaccine up taken in 1st dose | Pfizer/BioNTech | 8 | 56 | 1.642 (0.723-3.731) | 6.441 (1.921-21.598) | |

| Janssen (Johnson and Johnson) | 14 | 140 | 2.346 (1.221-4.508)* | 3.216 (1.073-9.643)** | 0.037 | |

| AstraZeneca | 38 | 162 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | Yes | 6 | 54 | 5.571 (1.804-17.203)* | 3.029 (2.406-9.133)** | 0.001 |

| No | 7 | 351 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Vaccination status | First dose only | 19 | 57 | 1 | 1 | |

| Second dose | 41 | 280 | 0.303 (0.137-0.673) | 0.75 (0.14-1.34) | ||

| Third dose | 0 | 21 | 2.276 (1.232-4.206)* | 1.75 (1.14-2.68)** | 0.009 | |

| NB: P-value <0.05**, P-value <0.02* statistically significant | ||||||

Table 5: Bivariable and multivariable analysis of factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022 (N=418).

Discussion

This study focused on SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa Public Hospitals, in 2022. The study participants were selected from the public hospitals. In this study 60 (14.4%) (95% CI 10.8-17.9) of participants were reinfected by SARS-CoV-2 after vaccination of at least one dose of the vaccine and having pre-vaccination infection history. IP training on COVID-19, Educational status, profession, Type of vaccine up taken in 1st dose, chronic respiratory diseases, number of vaccination status were significantly associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection after vaccination this factors are almost related to the study done in mid-western and in health care workers in the United Kingdom.

The finding of this study is higher than the study conducted in Vojvodina, Serbia, Europe that the overall incidence rate of reinfections was 5.99 (95% CI 5.89−6.09) per 1000 personmonths, a study in Midwestern healthcare employees with participants working in COVID-clinical and clinical units experiencing 3.77 and 3.57 times, respectively, greater risk of reinfection relative to those working in non-clinical units this difference may be due to the difference in viral strain, became common with the advancement of Omicron and delta, being in low economy, the difference in study area, time, study methodology, sample size.

The finding of this study is lower than that of a study done in Bangladesh a 37 (38.5%) of full-dose vaccinated people were infected with the virus. A study done in New Delhi, in India on breakthrough COVID-19 reinfections after vaccinations in healthcare and other workers in a chronic care medical facility conducted cross sectionally and found that, fter receiving any dosage of the vaccination, 19 people (16.9%) developed symptoms of COVD-19. A systematic review study found almost 20% of patients, the second infection may worsen their symptoms, and those who are old or immune-compromised may experience catastrophic problems, In a cohort study analyzing reinfection rates in Qatar, shows 22.2% reinfection (i.e., tested positive ≥ 45 days following the first positive test). This difference may be due to the difference in time, race, utilization of personal protective equipment.

A recent Swedish study found that, for a period of up to 20 months, natural immunity after three months was linked to a 95% reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and an 87% lower risk of COVID-19 hospitalization. Omicron, however, demonstrated a significant capacity for evading both naturally occurring and vaccine-induced immunity, resulting in diminished protection against reinfection but comparable protection against hospitalization or mortality brought on by reinfection. The fast growth of Omicron in South Africa resulted in a substantial rise in reinfections in mid-November 2021, in contrast to the beta and delta eras of dominance, during which there was no indication of immune evasion. Similar findings are significant to the dominance of Omicron globally and have also been documented in Qatar and the United Kingdom.

In this study health care professionals who didn’t take infection Prevention training on SARS-CoV-2 were significantly associated to professionals who took infection prevention training on SARS-CoV-2 (AOR=7.177: CI=4.761-9.698). The study conducted in Tertiary Care Hospitals of Peshawar, Pakistan states that health professionals who did not took training for SARS-CoV-2 is about 11 times more likely exposed for SARSCoV- 2. A study in Midwestern healthcare employees indicated 2.07 times and 2.28 times increased risk of COVID-19 recurrence among COVID clinical and clinical participants, respectively more reinfected by SARS-CoV-2. This may be due to that those health professionals who were trained on infection prevention may use the personal protective equipment properly.

The ODDs of health care professionals who has chronic respiratory diseases were significantly associated to those who had no history of chronic respiratory diseases (AOR=3.029: CI=2.406-9.133). This may be due to that health professionals who has chronic respiratory diseases is at high risk to be reinfected.

Regarding the vaccination status, health professionals who took only the first dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were significantly associated to those health professionals who took the 3rd booster doses (AOR=1.75: CI=1.14-2.68). A study done in Vojvodina is almost similar with that incompletely vaccinated (OR=1.50; 95%CI=1.37−1.63), were modestly more likely to be reinfected compared with recipients of a third (booster) vaccine dose. This may be due to the vaccination protocol is almost the same globally.

Profession, being a midwife was significantly associated to the other professions (AOR=9.315: CI=1.814-17.826). This may be due to that most midwives work in delivery and maternity wards and there may be crowded and low personal protective equipment utilization.

Strength and limitations

Strength of the study: It gives information about prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection status of vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Addis Ababa [20].

The findings can be used to guide future studies in Ethiopia and other low- and middle-income countries.

Limitation of the study: The researcher was unable to employ a systematic random sampling strategy due to the limited time available for the investigation. Instead, the study participants were recruited consecutively until the sample size reached.

Conclusion

This study showed the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among vaccinated health care providers with pre-vaccination infection history in Addis Ababa Public Hospitals, in 2022. The study participants were selected from the public hospitals. In this study, the magnitude of reinfection by SARS-CoV-2 after vaccination of at least one dose of the vaccine and having prevaccination infection history was high. IP training on COVID-19, Educational status, profession, Type of vaccine up taken in 1st dose, chronic respiratory diseases, number of vaccination status were significantly associated with SARSCoV- 2 reinfection after vaccination.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from research and ethical committee of Kea-Med college. Then this formal letter was submitted Addis Ababa research and emergency management directorate. Finally, the written formal letter was submitted to the selected hospitals. Informed written consent was obtained from all study participants. Participants were informed about the objective of the study. After information is provided about purpose of the study, confidentiality of the information and all the participants were reassured of the anonymous (unnamed), and as personal identifiers was not used.

Recommendations

To AARHB

• Giving infection prevention training on how to use infection prevention equipment for SARS-CoV-2 properly is recommended.

• Make available all PPE.

To hospital administrators

• Enforce health care provider to use the available PPE.

• Enforce health care provider to taking the vaccine according to the vaccinations. Schedule up to third dose is recommended.

• Individuals who had history of chronic respiratory diseases should seriously use PPE and also take the booster dose.

• Midwives should seriously use PPE.

References

- Gebru AA, Birhanu T, Wendimu E, Ayalew AF, Mulat S, Abasimel HZ, et al. Global burden of COVID-19: Situational analyis and review. Human antibodies. 2021;29(2):139-148.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rikitu Terefa D, Shama AT, Feyisa BR, Ewunetu Desisa A, Geta ET, Chego Cheme M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and associated factors among health professionals in Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2021:5531-5541.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ledford H. Six months of COVID vaccines: What 1.7 billion doses have taught scientists. Nature. 2021;594(7862):164-167.

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [PubMed]

- Berihun G, Walle Z, Berhanu L, Teshome D. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and determinant factors among patients with chronic disease visiting dessie comprehensive specialized hospital, northeastern ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:1795–805.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO SAGE roadmap for prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of limited supply: an approach to inform planning and subsequent recommendations based on epidemiological setting and vaccine supply scenarios, first issued 20 October 2020, latest update 16 July 2021. World Health Organization; 2021.

- Rivelli A, Fitzpatrick V, Blair C, Copeland K, Richards J. Incidence of COVID-19 reinfection among Midwestern healthcare employees. PloS One. 2022;17(1):e0262164.

- Huluka DK, Gebray N, Abera B, Yilak G, Sherman CB, Wolday D. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection: Two cases from Ethiopia. J Pan African Thorac Soc. 2021;2(2):114–116. [Crossref]

- kest H reda ali, Hassan N, Mahmoud NS. Epidemiological features, coping strategies for infection and the extent of reinfection with COVID-19 virus among nurses working in Tanta University hospitals. Int Egypt J Nurs Sci Res. 2022.

- Mathew S, Faheem M, Hassain NA, Benslimane FM, Al Thani AA, Zaraket H, et al. Platforms exploited for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):1–24.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Kaperak C, Sato T, Sakuraba A. COVID-19 reinfection: A rapid systematic review of case reports and case series. J Investig Med. 2021;69(6):1253–1255.

- Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, Kirwan P, Saei A, Atti A, et al. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19 Vaccination and Previous Infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207–1220.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menni C, Klaser K, May A, Polidori L, Capdevila J, Louca P, et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(7):939-949.

- Rahman S, Rahman MM, Miah M, Begum MN, Sarmin M, Mahfuz M, et al. COVID-19 reinfections among naturally infected and vaccinated individuals. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tyagi K, Ghosh A, Nair D, Dutta K, Singh P. Breakthrough COVID-19 infections after vaccinations in healthcare and other workers in a chronic care medical facility in New Delhi, India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2021;15(3):1007–1008.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adrielle dos Santos L, Filho PG de G, Silva AMF, Santos JVG, Santos DS, Aquino MM, et al. Recurrent COVID-19 including evidence of reinfection and enhanced severity in thirty Brazilian healthcare workers. J Infect. 2021;82(3):399-406.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dhumal S, Patil A, More A, Kamtalwar S, Joshi A, Gokarn A, et al. SARS-COV-2 reinfection after previous infection and vaccine breakthrough infection through the second wave of pandemic in India: An observational study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;118:95–103.

- Medic S, Anastassopoulou C, Lozanov-Crvenkovic Z, Vukovic V, Dragnic N, Petrovic V, Ristic M, Gojkovic Z, Tsakris A, Ioannidis J. Risk and severity of SARS-CoV-2 reinfections during 2020-2022 in Vojvodina, Serbia: A population-level study. medRxiv. 2022.

- Nisha B, Dakshinamoorthy K, Padmanaban P, Jain T, Neelavarnan M. Infection, reinfection, and postvaccination incidence of SARS-CoV-2 and associated risks in healthcare workers in Tamil Nadu: A retrospective cohort study. J Family Community Med. 2022;29(1):49.

[Crossref][Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fakhroo A, Alkhatib HA, Al Thani AA, Yassine HM. Reinfections in COVID-19 patients: Impact of virus genetic variability and host immunity. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):1–9.

- Ahmad J, Anwar S, Latif A, Haq NU, Sharif M, Nauman AA. Association of PPE Availability, Training, and Practices with COVID-19 Sero-Prevalence in Nurses and Paramedics in Tertiary Care Hospitals of Peshawar, Pakistan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;16(3):975–979.

[Crossref][Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Belay E (2023) Post-Vaccine SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection and Associated Factors among Health Care Providers with Pre-Vaccination Infection History in Addis Ababa Public Hospitals, Addis Ababa, 2022. J Vaccines Vaccin. 14:518.

Copyright: © 2023 Belay E. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.