Indexed In

- Academic Journals Database

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

- Scimago

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

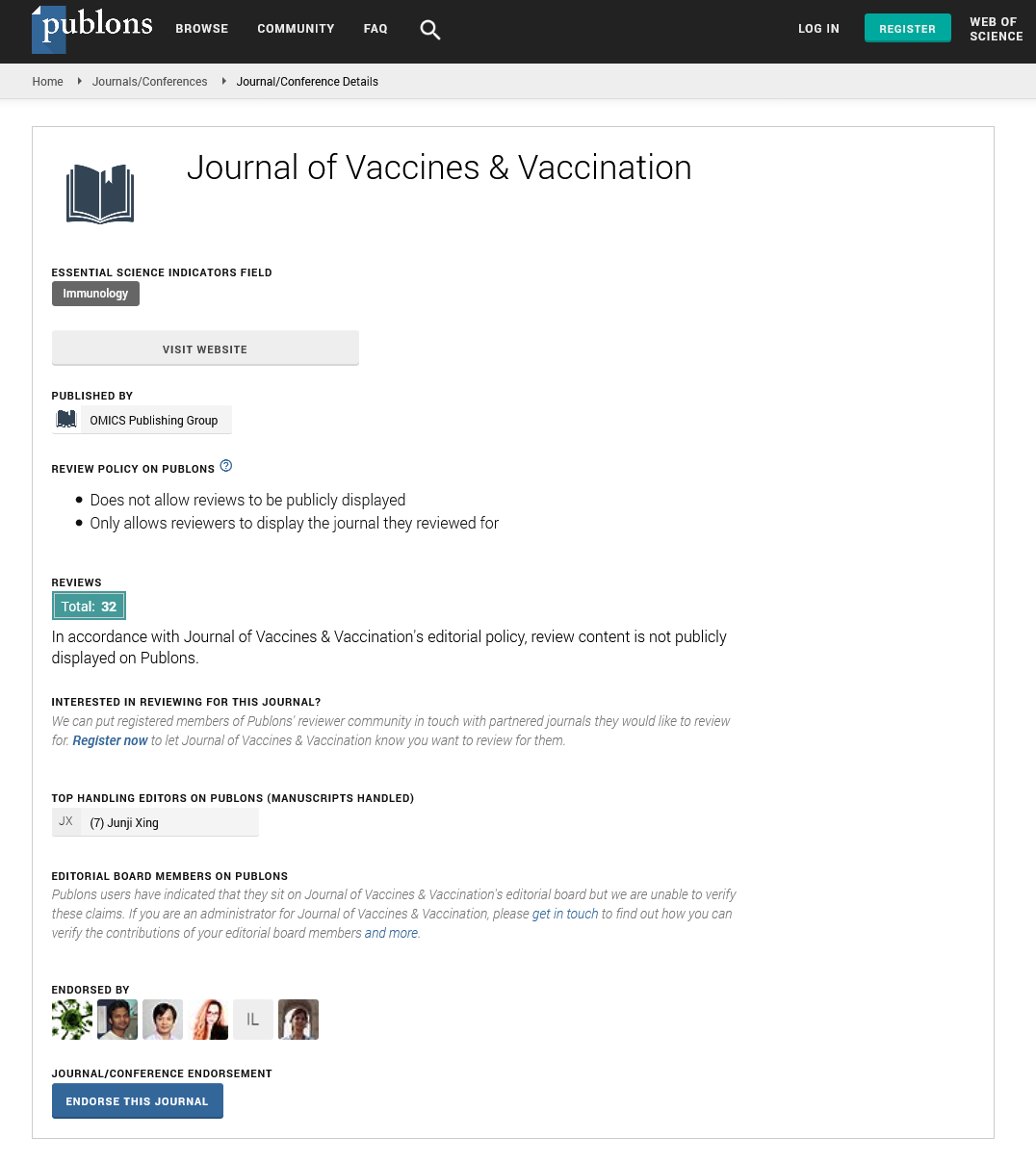

- Publons

- MIAR

- University Grants Commission

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Opinion Article - (2025) Volume 16, Issue 3

Polio Vaccines: A Key Weapon in the Fight against Poliomyelitis

Otolini Sabrna*Received: 01-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. JVV-25-29307; Editor assigned: 03-Mar-2025, Pre QC No. JVV-25-29307; Reviewed: 17-Mar-2025, QC No. JVV-25-29307; Revised: 21-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. JVV-25-29307; Published: 28-Mar-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2157-7560.25.16.596

Description

Poliomyelitis, or polio, is a highly contagious viral disease that has historically caused widespread illness and paralysis, particularly among children. Caused by the poliovirus, this disease primarily spreads through the fecal-oral route, often via contaminated food, water, or contact with an infected individual. While the majority of polio infections are asymptomatic or result in mild flu-like symptoms, a small percentage—about one in 200—can lead to irreversible paralysis. In severe cases, especially when the respiratory muscles are affected, the disease can be fatal. The development of vaccines against poliovirus marked a significant milestone in medical history, laying the foundation for the global effort to eradicate the disease.

Two main types of vaccines are used in the fight against polio: the Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV) and the Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV). IPV is administered via injection and is made from inactivated (killed) poliovirus. This vaccine stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies without posing a risk of causing the disease. IPV is widely used in routine immunization programs, especially in regions where the virus has been eliminated. It is safe, effective in preventing paralysis and is favored in countries with robust healthcare infrastructure.

In contrast, OPV contains live, attenuated (weakened) strains of the poliovirus and is administered orally, typically as drops. OPV has been a cornerstone of mass immunization campaigns due to its ease of administration and ability to induce strong intestinal immunity. This helps not only in protecting the vaccinated individual but also in stopping community transmission of the virus. However, the use of live virus in OPV carries a small risk. In very rare cases, the weakened virus can mutate and lead to Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus (VDPV) outbreaks or a condition known as Vaccine-Associated Paralytic Poliomyelitis (VAPP). These rare occurrences have prompted some countries to gradually transition to IPV-only immunization schedules after achieving polio-free status.

The administration of polio vaccines typically begins early in life. IPV is usually given as a series of injections starting at two months of age, followed by additional doses over time to ensure long-term protection. OPV, due to its oral delivery, is particularly effective in reaching large populations quickly during outbreak responses or in areas where healthcare access is limited. Both IPV and OPV require multiple doses to provide full and lasting immunity.

The effectiveness of these vaccines is well established. IPV is excellent at preventing the onset of paralysis caused by poliovirus but does not provide strong protection against intestinal infection, meaning the virus could still be spread by a vaccinated person. OPV, on the other hand, excels at stopping transmission by providing robust mucosal immunity in the gut. The combined use of both vaccines in different settings has contributed to an over 99% reduction in global polio cases since the late 1980s.

Both types of polio vaccines are generally considered safe. IPV, using a killed virus, has no risk of causing polio, while OPV's live virus is safe for the vast majority of recipients. The few risks associated with OPV are managed through careful monitoring and tailored vaccine strategies. This strong safety profile has enabled the vaccines to be delivered to millions of children globally with immense success.

The global impact of polio vaccination is profound. The launch of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) in 1988 has led to a dramatic drop in polio cases, from an estimated 350,000 annually to fewer than ten reported in recent years. Polio is now endemic in only a few countries, notably Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mass immunization campaigns have been crucial in breaking transmission chains and preventing new infections. As a result, millions of children have been spared the debilitating effects of paralysis and numerous lives have been saved.

Despite this progress, challenges persist in the final push toward eradication. Political instability, armed conflict and logistical difficulties can disrupt vaccination campaigns, especially in remote or conflict-affected regions. Additionally, misinformation and vaccine hesitancy, often fueled by rumors and distrust, can hinder immunization efforts. Vigilant surveillance, community engagement and education are essential to overcoming these barriers and maintaining high vaccination coverage.

Looking ahead, the future of polio vaccination involves continued commitment to immunization, research into safer and more effective vaccines and a transition toward IPV-only schedules once transmission is completely halted. Strengthening routine immunization systems and integrating polio vaccination with other public health services will also be vital to sustaining gains and preventing resurgence.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the global campaign to eradicate polio represents one of the most ambitious and successful public health efforts in history. Vaccines have played a central role in this success, drastically reducing the disease's prevalence and preventing countless cases of paralysis and death. The fight is not yet over, but with sustained global collaboration and a focus on reaching every child, the vision of a polio-free world is within reach.

Citation: Sabrna O (2025) Polio Vaccines: A Key Weapon in the Fight against Poliomyelitis. J Vaccines Vaccin. 16:596.

Copyright: © 2025 Sabrna O. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.