Awards Nomination

20+ Million Readerbase

Indexed In

- Academic Journals Database

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Electronic Journals Library

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- SWB online catalog

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

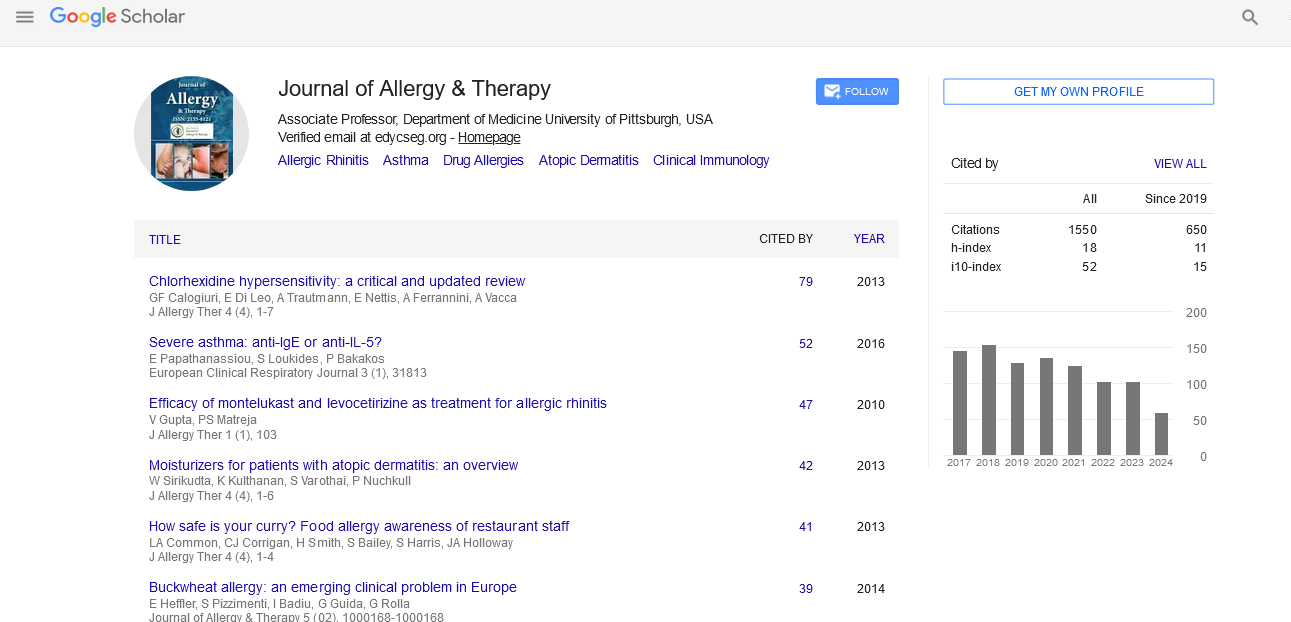

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences