Indexed In

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

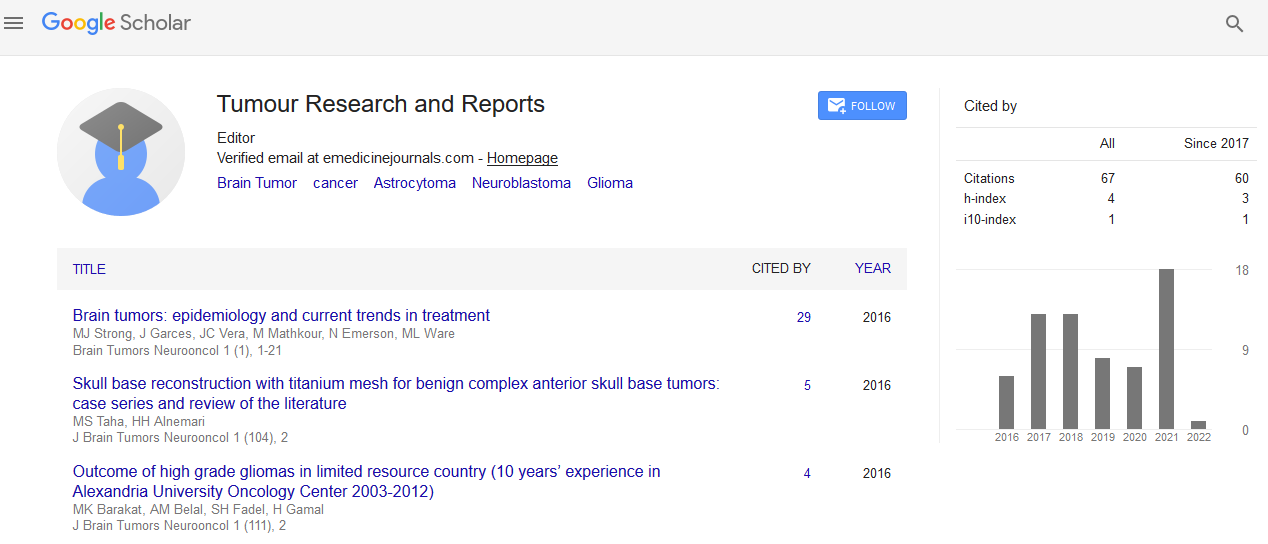

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Commentary - (2025) Volume 10, Issue 3

Evolving Resistance to Targeted Agents in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Molecular Adaptations and Clinical Considerations

Adrian Wexler*Received: 27-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. ACE-25-30164; Editor assigned: 29-Aug-2025, Pre QC No. ACE-25-30164 (PQ); Reviewed: 12-Sep-2025, QC No. ACE-25-30164; Revised: 19-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. ACE-25-30164 (RO); Published: 26-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2684-1614.25.10.265

Description

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) accounts for the majority of lung cancer diagnoses globally and remains a leading contributor to cancer-related deaths. Over the past two decades, the understanding of its molecular basis has led to major therapeutic developments. The use of small molecule inhibitors directed at specific genetic alterations has offered new treatment directions, particularly for individuals whose tumors carry mutations in genes such as EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, MET, and KRAS [1]. These agents have demonstrated substantial clinical benefit by interfering with the molecular signals that drive tumor cell proliferation and survival. Despite these improvements, a consistent challenge remains: the tumor’s ability to adapt and become less responsive to these agents over time [2].

This resistance is not uniform and can emerge through a variety of biological changes. In patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, the emergence of a secondary mutation in the same gene, such as T790M or C797S, has been frequently observed [3]. These changes reduce the drug’s ability to bind effectively, diminishing its therapeutic effect. Initially, third-generation EGFR inhibitors were developed to manage resistance driven by T790M, but additional alterations continue to appear during ongoing therapy, requiring further intervention [4].

Apart from secondary genetic alterations, tumor cells may switch to alternative signaling pathways. This means that even if the original target is blocked, the cancer cells find new ways to sustain growth. One known adaptation is MET amplification, which has been reported in various patients who no longer respond to EGFR inhibitors [5]. Similarly, bypass activation of HER2 or AXL can contribute to the same effect [6]. In some cases, these changes are not mutations but rather shifts in the activity level of certain genes or proteins.

Structural transformations in the tumor can also limit treatment effectiveness. For example, a proportion of NSCLC cases with EGFR mutations may transform into small-cell lung cancer after exposure to targeted agents [7]. This shift represents a drastic change in histology, requiring a different therapeutic approach. Though not fully understood, this transformation often involves concurrent loss of tumor suppressor genes such as RB1 and TP53 [8].

Another common resistance mechanism involves phenotypic changes where cells undergo Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). In this process, cancer cells adopt more mobile and invasive traits, making them less susceptible to inhibitors designed for a different cellular state [9]. This change in behaviour allows tumor progression to continue despite drug presence.

Drug exposure itself can influence tumor behaviour by exerting selective pressure. As treatment continues, clones with resistant properties begin to dominate the tumor population [10]. This clonal evolution complicates therapeutic decisions, as a treatment that was once effective no longer produces the same outcome. Repeated biopsies and molecular testing have helped identify such shifts, allowing clinicians to consider next-step therapies [11].

Managing resistance often involves sequential treatment with different inhibitors, each designed to target specific mutations or molecular events. In some cases, combinations of agents are used to delay or prevent resistance [12]. However, such strategies can come with increased toxicity and variable success. The use of liquid biopsies has allowed for more frequent monitoring of tumor DNA in the bloodstream, offering a less invasive method to detect changes that suggest declining drug effectiveness [13].

As tumors evolve, the importance of molecular profiling grows. Modern approaches involve next-generation sequencing to capture a broad spectrum of potential changes in the tumor genome [14]. These data guide clinicians in selecting agents that align with the current molecular makeup of the cancer. Even so, not all alterations have corresponding therapies, and some may signal an aggressive course regardless of treatment [15].

Patient response remains unpredictable due to inter-individual variation and the complex biology of resistance. Personalized monitoring and adaptive treatment strategies are increasingly seen as essential tools [16]. Integrating molecular diagnostics with clinical judgment allows for more accurate treatment adjustments, although access and cost remain challenges in many settings.

Ultimately, while targeted therapies have improved NSCLC treatment, resistance continues to affect long-term outcomes [17]. Understanding the tumor’s ability to adapt under therapeutic pressure is essential for developing strategies that maintain effectiveness and delay progression. Ongoing efforts in molecular research and clinical application will be vital in refining approaches to care and improving long-term disease control in this evolving cancer type [18].

Citation: Wexler A (2025). Evolving Resistance to Targeted Agents in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Molecular Adaptations and Clinical Considerations. J Tum Res Reports. 10:265.

Copyright: © 2025 Wexler A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.