Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

- SHERPA ROMEO

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Commentary - (2026) Volume 14, Issue 1

Eagle Syndrome and Ischemic Stroke: A Commentary

Qiuju Li, Bin Liu and Yuhui Wang*Received: 28-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. JVMS-24-26818; Editor assigned: 30-Aug-2024, Pre QC No. JVMS-24-26818 (PQ); Reviewed: 12-Aug-2024, QC No. JVMS-24-26818; Revised: 03-Feb-2026, Manuscript No. JVMS-24-26818 (R); Published: 10-Feb-2026, DOI: 10.350310/2329-6925.26.14.601

Description

The styloid process is a small, slender, and pointed bony projection of the temporal bone in the human skull. Located at the junction of the petrous and mastoid portions of the temporal bone, it extends anteroinferiorly from the base of the skull, near the mandible. This cylindrical structure typically measures about 2.5 cm in length and lies between the internal and external carotid arteries. Important surrounding structures include cervical blood vessels and cranial nerves V, IX, X, and XII. An Elongated Styloid Process (ESP) is defined as one exceeding 3 cm, with a prevalence of 4%-7.3% [1]. Not all ESPs cause symptoms; when they do, it is termed Eagle Syndrome (ES), affecting roughly 4% of individuals with ESP. First described by Watt Eagle in 1937 [2], ES is classified into classic and vascular types, based on the styloid angle and its anatomical relationships. Classic ES presents with pharyngeal discomfort, foreign body sensation, dysphagia, and facial pain, often leading patients to seek otolaryngological care. The vascular type, known as Stylocarotid Artery Syndrome (SAS), is rare, with an incidence of 4-8 per 100,000 [3], and is frequently misdiagnosed or overlooked. SAS may initially present as Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs) or stroke due to compression of the Internal Carotid Artery (ICA) by the elongated styloid process, causing stenosis or dissection. These patients are often misdiagnosed with common ischemic stroke and initially present to neurology departments.

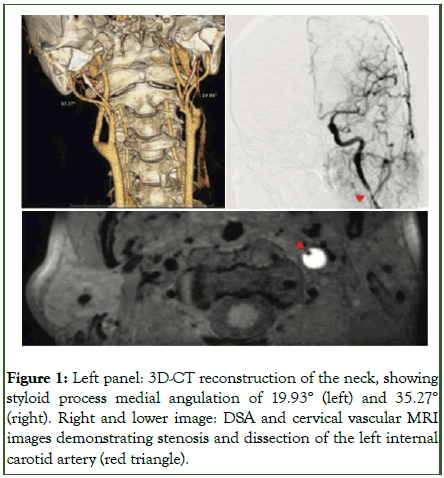

We previously reported a case of SAS in an early 30's male [4]. The patient experienced multiple TIAs before ultimately suffering a stroke. Prior to symptom onset, he engaged in vigorous exercise (badminton) and received a neck massage. Initially, he experienced recurrent transient aphasia, consistently occurring after neck flexion. Subsequently, he developed aphasia with memory impairment and sought emergency neurological care. After assessment, he received intravenous rt-PA thrombolysis and was treated following standard acute ischemic stroke protocols. During hospitalization, Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) revealed an abnormally elongated left styloid process compressing the Internal Carotid Artery (ICA), causing ICA dissection. Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) confirmed this diagnosis. Despite opting for conservative management, the patient showed good neurological recovery at discharge, with no significant residual deficits (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Left panel: 3D-CT reconstruction of the neck, showing styloid process medial angulation of 19.93° (left) and 35.27° (right). Right and lower image: DSA and cervical vascular MRI images demonstrating stenosis and dissection of the left internal carotid artery (red triangle).

Interested in Styloid Process Syndrome (SAS), we searched PubMed for recent studies. Over the past decade, 150 cases of Eagle syndrome were reported. We analyzed 23 of these cases where SAS caused ischemic stroke. Our review revealed two key trends:

- Is the distribution by gender and laterality statistically significant or merely coincidental?

- Could the male predominance be linked to more frequent engagement in vigorous physical activities?

- Are there underlying anatomical or physiological factors contributing to these differences?

While these preliminary findings have potential clinical implications, the current sample size limits definitive conclusions. We propose a larger, more systematic study to validate these observations. Future research should also explore other potential SAS-related factors, such as anatomical variations and genetic predispositions (Table 1).

| Time period | January 2014-April 2024 |

| Number of cases | 23 |

| Mean age at onset (years) | 48.45 ± 2.88 (range: 26-85) |

| Gender distribution | Male: 19 (82.6%), Female: 4 (17.4%) |

| Primary symptoms (n) | Hemiplegia: 20, Aphasia: 17, Sensory deficit: 6, Facial palsy: 5, Headache: 3 |

| Other symptoms (n) | Altered consciousness: 2, Neck pain: 2, Visual disturbance: 2, Neglect: 1, Tinnitus: 1, Palpitation: 1 |

| Mean NIHSS score | 10.82 ± 2.75 (n=11) |

| Elongated styloid process location (n) | Left: 5 (21.7%), Right: 1 (4.3%), Bilateral: 17 (73.9%) |

| Mean styloid process length (cm) | Left: 4.24 ± 0.99 (n=16), Right: 4.29 ± 1.31 (n=15) |

| Infarct location (n) | MCA territory: 6, Frontal lobe: 5, Parietal lobe: 5, Temporal lobe: 3, Insular lobe: 3, Periventricular: 3, Basal ganglia: 2 |

| Carotid artery dissection (n) | Left: 8 (34.8%), Right: 3 (13%), Bilateral: 6 (26.1%) |

| Styloidectomy performed (n) | 9 (39.1%) |

| Note: NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; MCA: Middle Cerebral Artery Search strategy: PubMed was searched using the following terms: ((ischemic stroke) OR (cerebral infarction)) AND ((Eagle syndrome) OR (stylocarotid artery syndrome)) |

|

Table 1: Literature review of ischemic stroke related to SAS.

Eagle Syndrome (ES) is a relatively common anatomical variant, with some cases of Elongated Styloid Process (ESP) progressing to ES. Stylocarotid Artery Syndrome (SAS) is a rare subtype of ES, with an incidence of approximately 4-8 cases per 100,000 individuals [3]. Diagnosing SAS requires high clinical suspicion, with particular attention to neurological symptoms associated with neck movement. The clinical manifestations of ES primarily relate to compression of surrounding nerves and vascular tissues by an elongated styloid process. Typical symptoms include facial pain or numbness and masticatory weakness (trigeminal nerve compression); otalgia, pharyngeal paresthesia, taste alterations, and dysphagia (glossopharyngeal nerve compression); dysphonia, diminished cough reflex, and heart rate changes (vagus nerve compression); and tongue deviation, dysarthria, and lingual atrophy (hypoglossal nerve compression). Some patients may have a palpable mass (elongated styloid process) in the tonsillar fossa during oropharyngeal examination. Due to the diverse symptomatology, ES patients may present to otolaryngology or neurology departments, but rarely to vascular surgery initially.

Imaging plays a crucial role in ES diagnosis: 3D-CT reconstruction of the neck clearly demonstrates styloid process morphology and its spatial relationship with adjacent structures, allowing accurate measurement of length and angulation; DSA reveals carotid artery stenosis and dissection, as well as the spatial relationship between the styloid process and vascular system; Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (TCD) also has diagnostic value for SAS. A case report [5] described a 56-yearold female with recurrent TIAs over 8 years, ultimately diagnosed with SAS through TCD neck flexion test and cured by surgical resection of the elongated styloid process. However, it should be noted that in addition to TCD, 3D-CT and DSA can also be used for neck flexion tests, but these tests carry potential risks of stroke induction and exacerbation of carotid artery dissection and should be used cautiously.

Once SAS is diagnosed, treatment options include conservative management and surgical intervention. Conservative treatment is like standard ischemic stroke management, primarily involving antiplatelet therapy and plaque stabilization, along with recommendations to avoid vigorous neck movements. However, conservative treatment carries risks of symptom recurrence and may negatively impact patients' psychological well-being, potentially inducing anxiety and depression.

Surgical treatment is considered curative for SAS, with intraoral and extra oral approaches being common techniques [6]. The intraoral approach offers advantages of minimal invasiveness and faster recovery, while the extra oral approach provides better surgical visualization and operative space. However, given the complex neurovascular structures surrounding the styloid process, surgical treatment also carries potential risks of complications such as nerve injury and hemorrhage, which partly explains why some patients prefer conservative management [7-9].

Currently, there is a lack of large-sample, long-term follow-up studies comparing the efficacy and safety of conservative versus surgical interventions. Therefore, treatment selection should be individualized, considering factors such as symptom severity, comorbidities, surgical risks, and patient preferences.

Conclusion

In summary, ESP is relatively common, while ES occurs less frequently, and SAS is even rarer. ES patients typically present with nerve compression symptoms, whereas SAS patients often have concomitant neurological deficits. Clinicians should be highly vigilant of patients presenting with cranial nerve symptoms or ischemic stroke manifestations associated with neck movement. For such patients, cervical 3D-CT and TCD examinations are recommended, with DSA considered when feasible. Neck flexion tests may be cautiously performed after thorough risk assessment. For confirmed SAS cases, treatment choice between conservative management and surgical intervention should be based on individualized risk assessment and patient preferences. Future research should focus on evaluating long-term outcomes of different treatment strategies and exploring novel minimally invasive surgical techniques to further optimize SAS management. Additionally, large-scale, multicenter studies are recommended to provide higher-level evidence-based medical evidence.

References

- Taneja S, Chand S, Dhar S. Stylalgia and styloidectomy: a review. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2023;22(1):60-66.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eagle WW. Elongated styloid processes: report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1937;25(5):584-587.

- Flame AC, Parker G, Halmagyi GM, Elliott M. Stylocarotid artery syndrome in a patient presenting with recurrent stroke. ANZ J Surg. 2023;93(7-8).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu B, Li Q, Zheng Y, Cai J, Jin H, Lin Y, et al. Ischemic stroke due to stylocarotid artery syndrome: a case report and review. J Int Med Res. 2024;52(5).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skjonsberg S, McLemore M, Sweet MP, Zierler RE. Transcranial Doppler for Eagle syndrome: rare presentation of unilateral internal carotid artery compression by the stylohyoid ligament with provocative maneuvers. J Vasc Ultrasound. 2018;42(1):18-22.

[Crossref]

- Dey A, Mukherji S. Eagle’s syndrome: a diagnostic challenge and surgical dilemma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2022;21:692-696.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cai W, Lee JG, Zalis ME, Yoshida H. Mosaic decomposition: An electronic cleansing method for inhomogeneously tagged regions in noncathartic CT colonography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;30(3):559-574.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lakare S, Chen D, Li L, Kaufman AE, Liang Z. Electronic colon cleansing using segmentation rays for virtual colonoscopy. Medical Imaging 2002: Physiology and Function from Multidimensional Images, San Diego, United States. 2002;4683:412-418.

- Chen D, Wax MR, Li L, Liang Z, Li B, Kaufman AE. A novel approach to extract colon lumen from CT images for virtual colonoscopy. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2000;19(12):1220-1226.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Li Q, Liu B, Wang Y (2026) Eagle Syndrome and Ischemic Stroke: A Commentary. J Vasc Surg. 14:602.

Copyright: © 2026 Li Q, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.