Indexed In

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

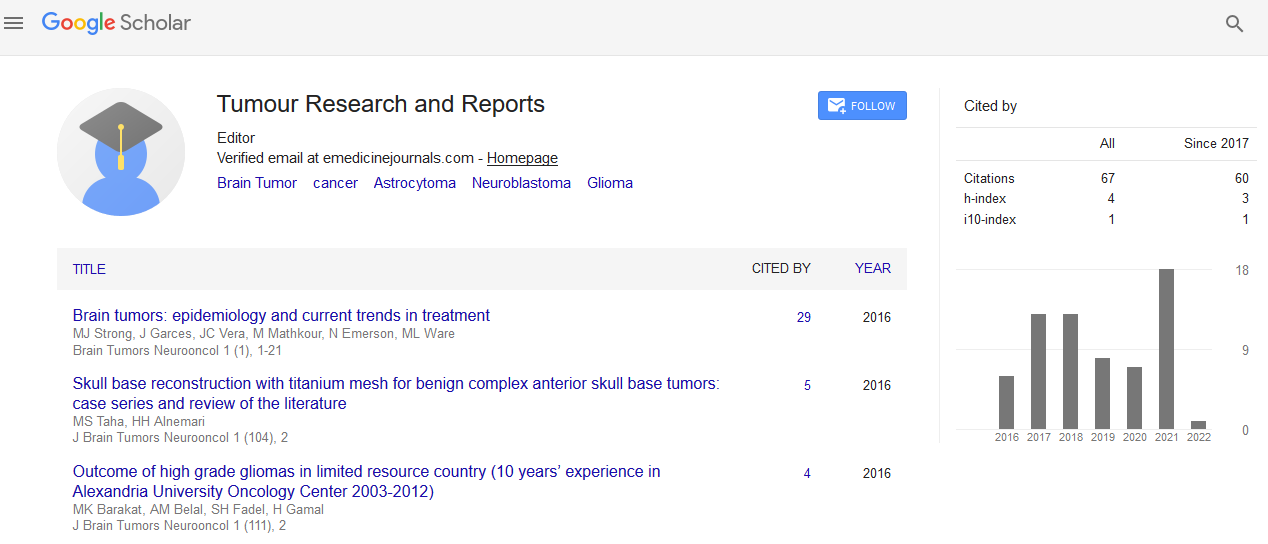

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Perspective - (2025) Volume 10, Issue 3

Cellular Strategies Driving Tumor Invasion and Immune Escape: Molecular Insights into Cancer Progression

Naomi Ellers*Received: 27-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. ACE-25-30166; Editor assigned: 29-Aug-2025, Pre QC No. ACE-25-30166 (PQ); Reviewed: 12-Sep-2025, QC No. ACE-25-30166; Revised: 19-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. ACE-25-30166 (R); Published: 26-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2684-1614.25.10.267

Description

Tumor development is not confined to abnormal cell growth alone. As cancer progresses, cells acquire traits that allow them to spread beyond their original location and persist despite the host’s immune defense. Two of the most concerning characteristics of malignant cells are their ability to invade nearby tissue and their capacity to avoid detection or destruction by immune surveillance. These features are not accidental but are shaped by specific biological changes that occur within the cancer cell and its surrounding environment.

Invasion refers to the process by which tumor cells penetrate surrounding tissue, cross barriers such as the basement membrane, and migrate toward blood vessels or lymphatic channels. This capacity is essential for metastasis, the process by which cancer spreads to distant organs. One of the main facilitators of this behaviour is the loss of normal cell-to-cell adhesion. Proteins such as E-cadherin are frequently reduced in invasive tumors, weakening the bonds that keep epithelial cells together. This shift allows cells to detach and become more motile.

At the same time, changes in the cytoskeleton an internal structure that helps determine cell shape and movement enhance a cell’s ability to migrate. Proteins such as RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 regulate cytoskeletal dynamics and are often upregulated or hyperactivated in invasive cancer cells. Their activity enables the formation of structures like lamellipodia and filopodia, which are used to crawl through tissue.

The tumor also produces enzymes that degrade the Extra Cellular Matrix (ECM), the structural network that normally limits cell movement. Matrix Metallo Proteinases (MMPs), especially MMP-2 and MMP-9, are commonly secreted by malignant cells or associated stromal cells to break down ECM components like collagen and fibronectin. This localized degradation removes physical barriers and allows tumor cells to advance into adjacent areas.

In parallel, the tumor microenvironment plays a substantial role in promoting invasion. Cancer-associated fibroblasts, a type of cell found within tumors, produce growth factors and enzymes that support invasive behaviour. Inflammatory signals from immune cells can further modify tissue architecture and influence cancer cell migration.

Beyond physical invasion, a major obstacle to long-term disease control lies in the tumor's ability to evade immune detection. Despite the presence of altered proteins and abnormal growth, many tumors are able to escape immune attack. One strategy involves reducing the visibility of tumor cells to the immune system. Malignant cells often downregulate molecules required for immune recognition, such as MHC class I proteins. These molecules normally display fragments of cellular proteins to cytotoxic T cells, which then determine whether a cell is abnormal. Without MHC class I, cancer cells are less likely to be targeted.

Another tactic is the secretion of immunosuppressive factors. Tumor cells can release molecules such as TGF-β, IL-10, and VEGF, which suppress immune cell activation and recruitment. These factors not only inhibit the function of T cells and natural killer cells but also promote the expansion of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells-two immune cell types that act to dampen immune responses.

Hypoxia, or low oxygen conditions often found within tumors, further supports immune evasion and invasive growth. In such settings, Hypoxia-Inducible Factors (HIFs) are stabilized and trigger the expression of genes that promote survival, mobility, and resistance to immune activity. These include VEGF, which drives new blood vessel formation, and several genes that promote metabolic reprogramming allowing tumor cells to thrive in low-nutrient environments while becoming less recognizable to immune cells.

Some tumors also mimic normal tissue processes to reduce immune activation. By expressing proteins that resemble nonthreatening tissue components or activating anti-inflammatory pathways, they create an environment less likely to provoke immune aggression. Moreover, genetic instability within tumors leads to frequent mutations, allowing them to evolve quickly and escape immune recognition, especially after initial treatment responses.

Collectively, these behaviours make malignant tumors especially difficult to treat effectively. Standard therapies may reduce tumor burden, but unless invasive capacity and immune evasion are addressed, recurrence and distant spread are likely. Understanding how tumor cells adapt to physical and immune barriers remains essential for improving long-term management strategies. By observing how these processes operate at the molecular level, it becomes possible to inform therapeutic decisions and identify new targets for intervention. Ongoing research continues to focus on dissecting these changes to better predict clinical behaviour and refine treatment choices based on individual tumor characteristics.

Citation: Ellers N (2025). Cellular Strategies Driving Tumor Invasion and Immune Escape: Molecular Insights into Cancer Progression. J Tum Res Reports. 10:267

Copyright: © 2025 Ellers N. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.