Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- ResearchBible

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture (AGORA)

- Electronic Journals Library

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- SWB online catalog

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- MIAR

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2015) Volume 0, Issue 0

Bartonella Infection: An Emerging Neglected Zoonotic Disease in Sudan

Abstract

Bartonella infection occurs in three forms: Cat scratch disease (CSD) due to Bartonella henselae, Trench fever due to Bartonella quintana and Carrión′s disease caused by Bartonella bacilliformis. CSD occurs worldwide and may be present wherever cats are found. The bacteria infect the red cells of cats which are usually symptomless. Transmission of the bacteria between cats is usually by fleas. Transmission to humans is by cat bites and scratches. In this paper we describe CSD for the first time in Sudan. Human cases were diagnosed pathologically at a single histopathology service center in Khartoum, Sudan. Following written informed consent, twenty four cases were enrolled in 2013, 2014 and the first quarter of 2015. The sites affected included the skin, subcutaneous tissue, lymph nodes, the lung, the spleen, brain, bone, breast, gallbladder and retro-peritoneum. In half of the cases (12/24; 50%), lymph nodes were infected. The majority (9/12; 75%) of the infected nodes were cervical. In the Hematoxylin and Eosin stained sections the bacteria were seen as clumps of black small filamentous structures. They stained positive for melanin by Masson Fontana and Melan-A. The bacteria were identified as Bartonella henselae by a specific monoclonal antibody. The disease may be more common than is realized. A high clinical index of suspicion has to be maintained to diagnose cases of Bartonella in Sudan.

Keywords: Bartonella henselae ; Cat scratch fever; Sudan

Introduction

Bartonella infection occurs in three forms: Cat scratch disease (CSD) caused by Bartonella henselae, trench fever due Bartonella quintana and Carrión's disease caused by Bartonella bacilliformis [1-4]. Trench fever is transmitted by the human body louse. Trench fever received this name during World War I, when many soldiers fighting in the European trenches harbored infected body lice and became infected with the Bartonella. Because of its association with body louse infestations, trench fever is now most commonly associated with homeless populations or areas of high population density and poor sanitation. Carrión's disease, formerly known as Bartonellosis, is transmitted by bites from sand flies (genus Lutzomyia) that are infected with the organism [4]. Carrión's disease has a limited geographic distribution; transmission occurs in the Andes Mountains at 3,000 to 10,000 feet in elevation in western South America, including Peru, Colombia and Ecuador. Most cases are reported in Peru [4]. Bartonellosis is endemic or potentially endemic to all countries. Any organ can be affected. Lymphadenopathy with suppuration, nervous system affection (encephalopathy, encephalomyelitis and coma) peripheral neuopathy, uveitis, blindness, muscle-skeletal manifestations, arthritis, skin lesions (erythema nodosum, maculopapular rash with pustules), osteomyelitis, fever and splenomegaly have been reported [5]. Prevalence of Bartonella infection varies considerably among cat populations with an increasing gradient from low in cold climates (0% in Norway) to high in warm and humid climates (68% in the Philippines) [6]. Most animal infections appear to be asymptomatic or had only mild clinical signs. Studies are hampered by diagnostic uncertainties and possibilities of co-infection with other microorganisms giving contradictory reports about the role of Bartonella in disease in animals. Experimental studies showed that cats inoculated with B. henselae can develop inflammatory swellings or pustules at the inoculation site and lymphadenopathy. Myalgia and transient fever with lethargy together with transient mild behavioral or neurological dysfunction, decreased responsiveness to environmental stimuli or increased aggressiveness were reported. While anemia, eosinophilia and reproductive disorders and Myocarditis were rarely reported [7].

As a genus, Bartonella is a group of intracellular pathogens that have in common a strategy that allows them to survive intra-cellularly within red cells and they disseminate throughout the body. Furthermore by living within the red cells they are able to escape the immune responses of the host [1]. Cat-scratch disease (CSD) was first described in 1931 and is caused by Bartonella henselae. CSD is considered by some as the most common cause of chronic lymphadenopathy among children and adolescents in some parts of the world. It manifests itself as sub-acute regional lymphadenitis with an associated inoculation site due to a cat scratch or bite, often accompanied by fever. A variety of changes occur in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. These include chronic inflammatory infiltrate that consists of lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells and neutrophils. Granulomas and areas of necrosis and fibrosis are seen in some cases. Vascularity is always present and varies in intensity. Bartonella species in lesions appear as aggregates of black bacteria that stain positive for melanin with Warthin Starry stain. The disease can be wide spread in children [3,8].

Bartonella henselae is an aerobic, oxidase-negative, slow growing Gram negative and slightly curved rod. It does not have flagella to facilitate its movement; however, there has been evidence of twitching motility. The bacteria are found in red cells and can be isolated from erythrocytes of cats as well as skin nodules and lymph nodes of infected humans. An unusual feature of Bartonella henselae is its inability to use glucose to derive energy. This is due to the fact that it has an incomplete glycolysis pathway. Bartonella henselae uses succinate and glutamate along with histidine, asparigines, glycine and serine from the growth medium. It also grows inside endothelial cells and destroys the red cell it infects and hemosiderin can be demonstrated in lesions. One of the priorities of the organism is to ensure a good blood supply and cause angiogenesis early in the site it infects [9].

In 1969 a single case of Bartonella infection was reported from Sennar south of the capital Khartoum, Sudan [10]. The organism was reported as Bartonella quintana. At that time specific antibodies against Bartonella henselae were not available. From the clinical data and morphology it was most likely Bartonella henselae.

This paper describes, for the first time case series of Bartonella henselae in Sudan. It is possible that the disease might have been missed in the past.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The study proposal was approved by the Ethics Committee of Institute of Endemic Disease, University of Khartoum. Written informed consents were obtained from adults/parents of 4 children.

Cases were referred as biopsies or infected whole organs to EL Hassan Histopathology Laboratory in Khartoum. Until the 8th of April 2015, 24 cases of Bartonella henselae were diagnosed at the laboratory. None of the cases biopsied were clinically diagnosed as Bartonella infection.

Biopsies from the cases were fixed in neutral formalin saline. Sections were cut from different parts of the material submitted. They were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin and with Warthin Starry (WS) stain, Masson Fontana and Melan-A for melanin. Aggregates of small black filamentous structures in the H&E stained sections suggested Bartonella organisms. These were confirmed by a mono-clonal antibody specific for B henselae. It was a Mouse monoclonal antibody: Anti-Bartonella henselae antibodies (Mouse monoclonal, H2A10, ab704, abcam, USA) were used in this study. 1:100 dilutions for the primary antibody were performed. Serial 4 µm sections were cut from each specimen. The sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated in graded alcohol. For heat-induced epitope retrieval, the sections were subjected into High pH buffer (pH 9.0) in a water bath at 95°C for 20 minutes. Immunostain was then performed according to the manufacturer protocol. For this, 3% H2O2 for endogenous peroxidase blocking was applied for 5 minutes. Slides were then washed 2 × 5 minutes in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Power block (Biogenex. QD600-60KE) was applied for 10 minutes at room temperature. Slides were then drained for 5 seconds and tissue paper was used to wipe around the sections. Primary antibody was then applied and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. The slides were then rinsed 2 × 5 minutes in PBS. After this step slides were incubated with super enhancer solution (Biogenex, QD420-YIKE) for 20 minutes, washed twice in the buffer and incubated with Polymer-HRP (Biogenex, QD420-YIKE) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Slides were then washed in buffer for 15 minutes. Chromogenic substrate was then added and incubated for 10 minutes or until desired reaction is achieved. Slides were then rinsed 4 times in buffer. Drops of Hematoxylin were added to cover the section and sections were incubated for 1 minute. Finally slides were rinsed in tap water and mounting medium was used to cover the section.

Cross-reactivity tests were performed on B. henselae, B. quintana, B. bacilliformis, B. elizabethae, B. grahamii, B. taylorii, B. doshiae, and B. vinsonii strains. Reactivity was only obtained with Bartonella henselae. All B. henselae strains were found positive with this antibody. Spirochetes, Helicobacter pylori and M. tuberculosis were also found to be negative. The cell phenotypes in the lesion were identified by indirect Immuno-peroxidase stains against CD3, CD20 and CD68. CD34 was used for identification of blood vessels.

Results

The sites affected in the 24 cases are shown in Table 1. The majority (20/24; 83.3%) of patients were adults with only four patients below 12 years of age. The affected four children were males with a mean age of 6.8 ± 4.6 years. Eleven of the remaining patients were females with a mean age of 38 ± 18.9 years. The rest (n=9) were males with a mean age of 42.0 ± 14.7 years. The sites affected included: the skin, subcutaneous tissue, lymph nodes, the lung, the spleen, Brain & spinal cord, bone, breast and retro-peritoneum. Twelve of the 24 cases (12/24; 50%) had enlarged lymph nodes that were positive for B henselae infection. Nine (9/24; 37.5%) of the nodes were cervical, two (2/24; 8.3%) were inguinal, one (1/24; 4.2%) was mediastinal. Those with superficial nodes complained of fever and swellings at the sites affected. Eight (8/24; 33.3%) of the patients were from Port Sudan which is known for its high numbers of cats. The rest of the patients were from different parts of the country. The patient who had a large retroperitoneal infection and the other who had an infected spleen complained of pain, fever and loss of weight. A female patient from Darfur in Western Sudan reported with subcutaneous nodules associated with mild lung infection. She looked remarkably well. Chest X-ray showed small nodules in the right lower lobe. Sections from the subcutaneous nodules and smears from the sputum were positive for B henselae. The sputum was negative for tubercle bacilli. No further information is available about her. She and the patients with Bartonella of the spleen and the retroperitoneum were HIV negative. In none of the cases was the clinical diagnosis of Bartonella considered.

| Patient's ID | Age | Gender | Site | Year of diagnosis |

| 1 | 12 | Male | Spleen | 2013 |

| 2 | 2 | Male | Lung | 2013 |

| 3 | 42 | Male | Inguinal lymph node | 2013 |

| 4 | 50 | Male | Cervical lymph node | 2013 |

| 5 | 23 | Female | Cervical lymph node | 2013 |

| 6 | 33 | Female | Brain [left parito-temporal lobe | 2013 |

| 7 | None reported | Male | Brain | 2014 |

| 8 | 58 | Male | Lower Limb skin | 2014 |

| 9 | 35 | Male | Inguinal lymph node | 2014 |

| 10 | 28 | Male | Shoulder mass | 2014 |

| 11 | 30 | Female | Breast | 2014 |

| 12 | 69 | Female | cervial lymph node | 2014 |

| 13 | 40 | Male | Oesphagus [Carcinoma+Bartonella] | 2014 |

| 14 | 35 | Male | Retro-peritoneal | 2014 |

| 15 | 60 | Female | Skull | 2014 |

| 16 | 29 | Female | Cervical lymph node | 2014 |

| 17 | 4 | Male | Cervical lymph node | 2014 |

| 18 | 22 | Female | Mediastinal lymph node | 2014 |

| 19 | 24 | Male | Cervical lymph node | 2014 |

| 20 | 19 | Female | Brain [temporal lobe] | 2014 |

| 21 | 9 | Male | Cervical lymph node | 2014 |

| 22 | 69 | Female | Cervical lymph node | 2014 |

| 23 | 39 | Female | Cervical lymph node | 2015 |

| 24 | 70 | Male | Gall Bladder | 2015 |

Table 1: Bartonella henselae infection: year, age sex and site of infection.

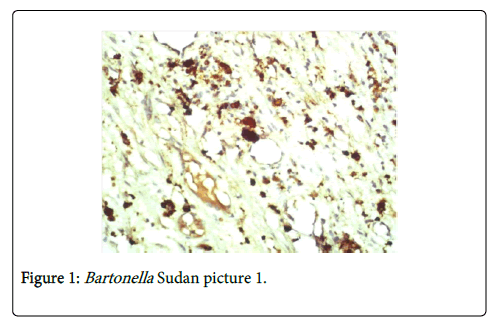

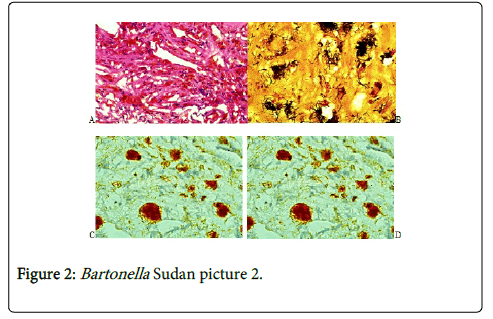

In H&E stained sections there was a chronic inflammatory cellular reaction, vascularity and fibrosis (Figure 1A). The inflammatory cells included lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells and neutrophils. Epithelioid granulomas with Langerhans giant cells were uncommon. They were usually seen in lymph nodes. Areas of necrosis were seen in some cases particularly in the spleen and the retroperitoneal mass. Scattered in this inflammatory reaction are aggregates of black bacteria that suggested Bartonella infection (Figure 1). Vascularity was always present and varied in intensity (Figure 2A). The mononuclear cells in the lesion were identified as a mixture of CD 20+ B cells, CD 3+ T cells and CD 68+ macrophages. The bacteria were positive for the melanin stains: Masson Fontana, Warthin Starry stain and Melan-A (Figures 2B and 2C). The bacteria were confirmed to be B. henselae by specific monoclonal antibody (Figure 2D).

Discussion

CSD occurs worldwide and may be present wherever cats are found. Stray cats may be more likely than pets to carry Bartonella. Ticks may carry some species of Bartonella bacteria, but there is currently no convincing evidence that ticks can transmit Bartonella infection to humans. The disease occurs most frequently in children under 10 years [11]. Cats can harbor infected fleas that carry Bartonella bacteria. These bacteria can be transmitted from a cat to a person during scratching at the site of contact with a cat or because of a cat bite. This causes a nodule in the skin and often an enlarged infected lymph node. Inoculation site typically arises about 3 to 10 days after the initial injury, and a visible inoculation site is present in approximately 65% of patients [3]. The lesions may be papules or pustules and the organisms may reach the regional lymph nodes causing lymphadenitis. A single lymphatic nodule is involved in about 50% of the cases; multiple regional nodes occur in around 20% of cases. CSD usually is benign and self-limiting in immunocompetent individuals, with regression of the lymphadenopathy within 2 to 6 months. However, in rare cases, enlarged nodes may persist for years. Patients with atypical manifestations of CSD often lack the characteristic superficial lymphadenopathy and inoculation site papule and initially might be misdiagnosed as having other infectious processes or neoplasms. The lymph nodes range from 1.0 to more than 10.0 cm in size, and often there is striking erythema of the overlying skin. The results of routine laboratory studies usually are unremarkable, with the occasional mild leukocytosis, eosinophilia or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Histopathology with typical aggregates of WS positive filaments are the feature of Bartonella.

Bartonella henselae has common and uncommon clinical manifestations. The typical clinical forms are fever and localized lymphadenopathy only, prolonged fever and hepatosplenic disease. The less common forms are many and include: neuroretinitis, encephalopathy, epilepsy, transverse myelitis, glomerulonephritis, endocarditis and others. Splenic, brain and retroperitoneal forms were reported in our setting [12].

The histologic differential diagnosis of CSD lymph-adenitis primarily includes: Kikuchi necrotizing lymph-adenitis (KNL), Kawasaki disease and other infectious processes, such as tuaremia, mycobacterial infection, brucellosis, fungal infection, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) and lymphadenitis associated with idiopathic granulomatous mastitis [13].

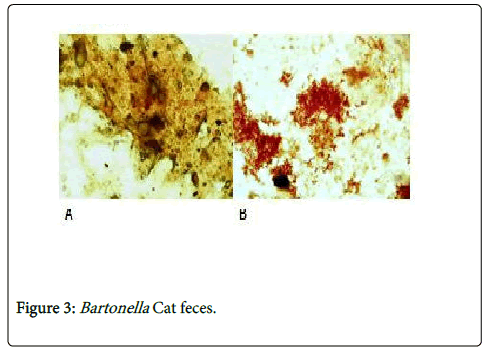

We diagnosed the first documented case of Bartonella henselae in 2003. No more cases were seen till 2013. Since 2013 we started seeing more Bartonella henselae cases. Until the 8th of April 2015, 24 cases of Bartonella infection in various organs at EL Hassan Centre for Histopathology, Khartoum. The highest prevalence seen in adults is probably due to the fact that the samples came from one referral centre. Larger sample size could reflect a different prevalence pattern. Lymph nodes were the most commonly affected site in our series. The brain, skin, subcutaneous tissue, the lung, the spleen, spinal cord, bone, breast, retroperitoneum, gallbladder were affected at variable frequencies. None of these cases were suspected clinically. This highlights the need to have a high index of suspicion to reach a definitive diagnosis in cases of CSD in Sudan. Recently, we could demonstrate the bacteria in the feces of cats that leave their excreta outdoors (Figures 3A and 3B). The organisms are Gram negative Warthin Starry positive bacteria. This Bartonella we found was identified as B henselae by a specific monoclonal antibody. We believe that cases of Bartonella are missed clinically and the disease may be more common than we presented here. About 3 years ago there was an outbreak of PUO in and around two small cities north and south of the capital Khartoum. During the outbreaks there were large numbers of fleas. It is possible that the outbreak was due to B henselae. There is therefore a need to monitor the situation in the future particularly in these two areas.

We saw 3 cases of Bartonella henselae infecting the brain (reported in separate under-preparation manuscript). Encephalitis is the most frequent manifestation, but radiculitis, polyneuritis, myelitis, cranial nerve involvement and neuroretinitis have been reported. Neurological changes generally arise approximately 2 weeks after the onset of fever and superficial lymphadenopathy and the bacteria are usually present in the cases. Seizures are the most common initial symptom, headache, mental status changes, delirium and coma also might occur. Most patients recover completely within 1 year without sequelae [11,14].

Laboratory diagnosis of Bartonella henselae infections can be accomplished by serology or PCR on biopsy samples [2]. Immunofluorescence detection (IFD) was used and a commercial serology assay (IFA) was compared with PCR for the detection of B henselae [14,15]. Among 200 lymph nodes examined from immunocompetent patients, 54 were positive for by PCR, of which 43 were also positive by IFD. Among the 146 PCR-negative lymph nodes, 11 were positive by IFD. Based on PCR results, the specificity of this new technique was 92.5%, the sensitivity was 79.6%, and the positive predictive value was 79.6%. At a cutoff titer of 64, the sensitivity of the IFA was 86.8% and the specificity was 74.1%. Since PCR-based detection with biopsy samples is available only in reference laboratories, it was suggested that using IFD coupled with the commercial serology test for the diagnosis of CSD is appropriate [2,14,15]. We had no information if the patients reported here had been treated with erythromycin which is available in the country. It is possible that the majority of the patients cannot afford to buy the drugs. We should try in the future to tap resources from the local NGOs for treating Bartonella infection. We have not examined for flees and other possible vectors of Bartonella henselae.

Conclusion

Bartonella henselae infection in humans in Sudan is a neglected zoonotic disease that is more common than is realized. A high index of suspicion has to be maintained to diagnose possible cases.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their thanks to the staff at EL Hassan Centre for Histopathology for their kind assistance during the conduct of the study.

References

- Klein JD (1994) Cat scratch disease. Pediatr Rev 15: 348-353.

- Scott MA, McCurley TL, Vnencak-Jones CL, Hager C, McCoy JA, et al. (1996) Cat scratch disease: detection of Bartonella henselae DNA inarchival biopsies from patients with clinically, serologically, and histologically defined disease. Am J Pathol 149: 2161-2167.

- Smith DL (1997) Cat-scratch disease and related clinical syndromes. Am Fam Physician 55: 1783-1789.

- Debre R, Lamy M, Jamett ML (1950) La maladie des griffes dechat. Sem Hop Paris 26: 1895-1904.

- Berger S (editor). Bartonellosis: Global status-2015 edition. GIDEON Informatics, Inc. Los Angles, California, USA.

- Boulouis HJ, Chang CC, Henn JB, Kasten RW, Chomel BB (2005) Factors associated with the rapid emergence of zoonotic Bartonella infections. Vet Res 36: 383-410.

- (2012) Bartonella Infections in Animals: Clinical Signs.

- Chang CC, Lee CJ, Ou LS, Wang CJ, Huang YC (2015) Disseminated cat-scratch disease: case report and review of the literature. Paediatr Int Child Health.

- Chenoweth MR, Somerville GA, Krause DC, O'Reilly KL, Gherardini FC (2004) Growth Characteristics of Bartonella henselae in a Novel Liquid Medium: Primary Isolation, Growth-Phase-Dependent Phage Induction, and Metabolic Studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 656-663.

- Wernsdorfer G (1969) Possible human Bartonellosis in the Sudan: clinical and microbiological observations. Acta Tropica 26: 216-234.

- Ronen BA, Moshe E, Boaz A, Eugene K, Merav V, et al. (2005) Cat Scratch Disease in the Elderly patients. Clin Infect Dis 41: 969-974.

- Florin TA, Zaoutis TE, Zaoutis LB (2008) Beyond Cat Scratch Disease: Widening Spectrum of Bartonella henselae Infection. Pediatrics 121: e1413-1425.

- Shin OR, Kim YR, Ban TH, Lim T, Han Th, et al. (2014) A case report of seronegative cat scratch disease, emphasizing the histopathologic point of view. Diagn Pathol 9: 62.

- Breitschwerdt EB, Sontakke S, Hopkins S (2012) Neurological Manifestations of Bartonellosis in Immunocompetent Patients: A Composite of Reports from 2005-2012. J Neuroparasitol 3: 1-15.

- Rolain JM, Gouriet F, Enea M, Aboud M, Raoult D (2003) Detection by Immunofluorescence Assay of Bartonella henselae in Lymph Nodes from Patients with Cat Scratch Disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 10: 686-691.

Copyright: © 2015 Hassan et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.